Posted by Oliver Creighton

24 March 2025The word ‘iconic’ is probably one of the most over-used in the English language, but the team of researchers behind the Medieval Warhorse Project, which ran between 2019-23, has never had any hesitation in using the word to characterise … well … one of the great icons of the medieval period.

For many, the image of the armoured knight mounted on his charging warhorse captures the very essence of the Middle Ages. As distinctive symbols of social status, horses were central to the medieval aristocratic and knightly image and closely bound up with concept of chivalry, the very word which derives from the French for ‘horseman’ (chevalier), while as weapons of war bred for size, strength and stamina, they changed the face of battle.

While previous studies of the subject had been dominated by historians, the Warhorse Project aimed to show how an archaeologically led approach could generate new knowledge about horses, what they looked like, how they evolved and their changing place in the medieval world. Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and running from 2019 to 2023 the work was a collaborative research endeavour led by archaeologists from the University of Exeter working alongside historians at the University of East Anglia. The research also had a strong partnership-working ethos, involving the Royal Armouries, who provided access to their world-leading collection of horse armour, and the Portable Antiquities Scheme, one of the great success stories of modern British archaeology, which has created and curated a vast database of portable objects including many thousands of medieval horse-related items.

The project prided itself on drawing upon the widest possible array of evidence, bringing together many different specialists in a multi-faceted approach where the strengths of one line of evidence compensated for the shortcomings of others. Our work saw archaeological scientists, who measured horse bones and took samples for DNA and isotopic analysis, working alongside material culture experts who mapped and analysed equestrian artefacts. Historians, meanwhile, combed hundreds of documents to unlock information about horse breeding and training facilities, while other crucial information was provided by the standing remains of equestrian facilities and iconographic sources including wall paintings and sculpture.

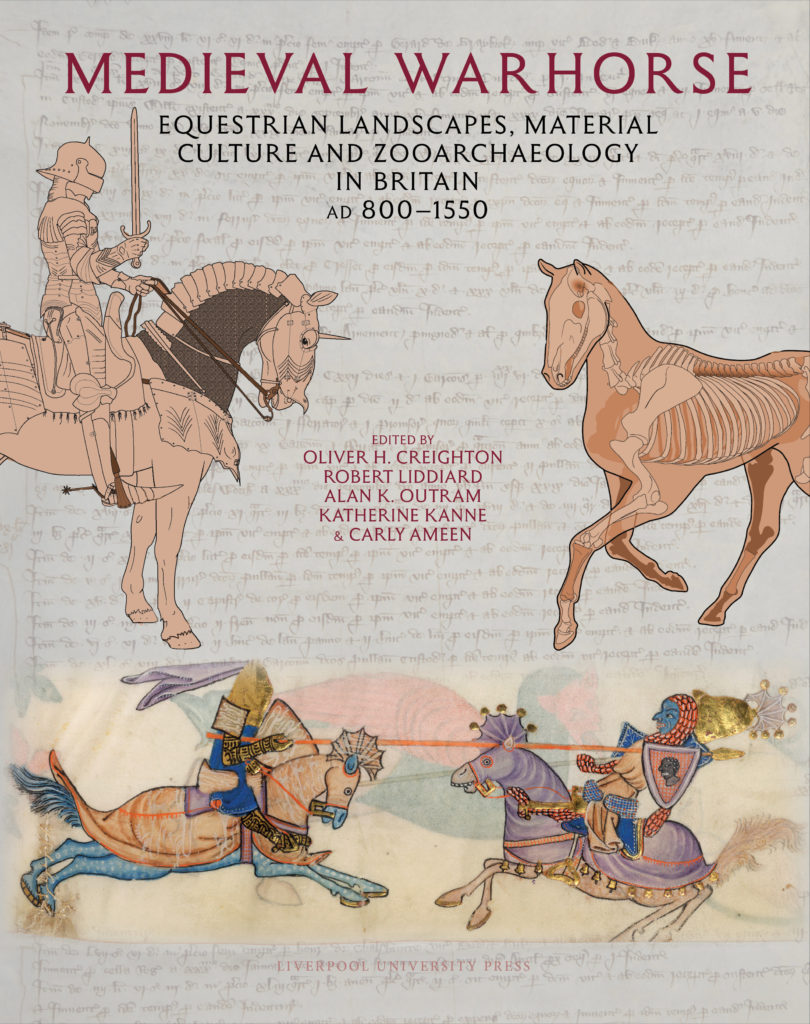

We’re thrilled to announce the imminent publication of a new monograph resulting from the project: Medieval Warhorse: Equestrian Landscapes, Material Culture, and Zooarchaeology in Britain, AD 800–1550. It is very much a team effort, with a large array of authors including the project investigators, post-doctoral researchers and PhD and MA students. As well as being an academic output that captures the project’s findings, we hope thatMedieval Warhorse will appeal widely — for anyone curious about medieval warfare, horse history, or medieval archaeology. The volume is published in full colour and you can even get a healthy 30% discount if you order early (click here for details)!

We are hosting a book launch, both online and in-person at the University of Exeter, on 27th March — everyone is welcome.

How can you summarise the findings of such a wide-ranging project in a short blog? Rather than attempt that, I will make just one observation — that the most rewarding parts of our research journey have not been discoveries based on one source, but the excitement when different approaches and lines of evidence collide, sometimes corroborating the other, but other times not … A good example, covered in detail in the book, is what the project has told us about warhorses in the eleventh century and the impact, or otherwise, of the Norman Conquest on the English equestrian world. Our zooarchaeological study of many thousands of horse bones from hundreds of sites indicated a small but clear dip in horse stature around the time of the Conquest, which might seem counter-intuitive given everything we know — or assume — about Norman cavalry and horse-breeding. Actually, when we look hard at the iconographic evidence for horses in the period we find intriguing depictions of gracile horses, some with noticeably spindly legs, on seals and on wall paintings. Other lines of evidence point to long-term continuity in horse culture across the Saxo-Norman period. We certainly see long-term stability in the choice of the environments and landscapes where horses were bred, and we see it also in terms of horse gear.

In material terms the Norman Conquest did not witness any sort of equestrian ‘event horizon’; little changed in terms of horseshoes or stirrups for example, although one significant difference was the post-Conquest introduction of the ‘curb’ bit, which tells us about changing horsemanship rather than the decoration or stature of animals. Another perspective in this issue was provided by the project’s pan-European synthesis of bone data carried out as part of a linked PhD project: the ‘dip’ in stature turned out not to be particular to England but was instead part of much a wider phenomenon, which for the moment remains unexplained. Overall the Norman Conquest wasn’t quite the turning point for warhorses that many believed, in archaeological terms at least; instead it is one of a series of smaller horizons of change, which also include the reign of King Cnut before the Norman Conquest and the reign of King Stephen in the mid-twelfth century, both of which seem to have witnessed profound alterations in the appearance, uses and decoration of horses.

Our work continues in many areas. We have further papers planned and future outreach activities brewing, so watch this space. Our ‘end of project’ monograph is hopefully another beginning.

Our project website contains full details of our work, including links to our publications and blogs. You can also access and download the datasets the project produced via the Archaeology Data Service.

Cover image: depiction of two groups of lance-armed knights charging at one another, on a thirteenth-century fresco in La Tour Ferrande, a seigneurial tower at Pernes-les-Fontaines, Vaucluse, France. Photograph: Oliver Creighton. The medieval horse-related artefacts in the composite image above are courtesy of the Portable Antiquities Scheme, and include [a] Stirrup-strap mount, copper alloy. 11th/12th century, West Yorkshire; [b] Stirrup-strap mount, copper alloy. Mid- to late 11th century, Wiltshire; [c] Harness pendant, gilt copper alloy. 13th/14th century, Wiltshire; [d] Armorial harness pendant, gilt and enamelled copper alloy. 13th century, Kent; [e] Harness pendant with bell-shaped pendant (second one missing), copper alloy. Late 12th/13th century, Lincolnshire; [f] Harness pendant with bell, gilt copper alloy. 14th century; [g] Horse harness strap distributor, copper alloy. 13th/14th century, Lincolnshire; [h] Curb bit (fragment), copper alloy. Late 11th/early 12th century, Gloucestershire.