Posted by Clementine Pursey

19 May 2025The blog’s ‘spotlight’ series gives a glimpse into the lives and research of the Centre’s members. This week, we’re playing host to another member of our thriving postgraduate community, as Clementine Pursey, PhD student on the Learning Anglo-French project, introduces us to their fascinating work.

I study how the use of prestige languages, such as Anglo-French and Latin, influenced the social identities of women in medieval England.

I had absolutely no interest in medieval studies until my final semester of undergrad. As my degree was in French and History, I always wanted to study them together but could never quite figure out how. This was until my final semester, when I started to think about the politics of dialects versus languages. I ping-ponged between Occitan and Anglo-French but couldn’t decide which direction to take until I saw the PhD studentship with the Learning Anglo-French project advertised.

My focus on women’s use of language emerged from my long-standing interest in feminist theory, which led me to explore how gender is constructed in different cultures. This made me particularly interested in how factors like language and social conventions shape a culture’s own unique concept of “women”. Nuns are a specific focus of my research because of the wealth of manuscripts and other historical artefacts we have from nunneries, which make them ideal for building case studies.

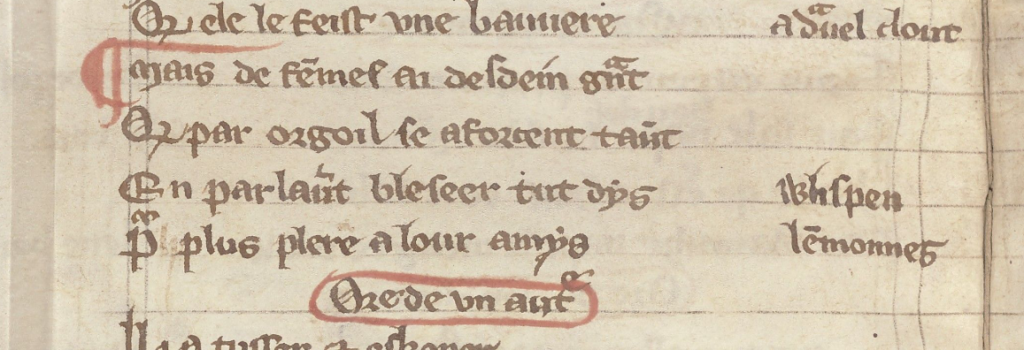

My thesis focuses on the nuns of Lacock Abbey in the fourteenth century, but my interest in nuns was sparked by the medieval community at Barking Abbey and their incredible collection of Anglo-Norman saints’ lives (British Library Additional MS 70513). It was through this collection that I replicated the very process that I now study, as I learned to read the French Vie d’Edouard le Confesseur by a Nun of Barking (who translated the life into the vernacular). You can imagine my disappointment when, after immersing myself in the hagiographical version, I finally read historical records of Edward the Confessor’s life and found that they weren’t quite as exemplary!

At this point, I have two main sources that are the backbone of my thesis: British Library Additional MS 46919 and Yale University, Beinecke Library, MS Osborn a56. These are both compilation manuscripts owned by religious figures in early-fourteenth century England, linked through their inclusion of Walter de Bibbesworth’s Tretiz. Osborn a56 is particularly exciting to work on, both because of its late “discovery” in 2011 and its original owners being the nuns of Lacock Abbey. This isn’t to say that BL Add. MS 46919 isn’t equally as thrilling – inside, we find some of the earliest translations of Latin hymns into English, scribed by its owner William Herebert of Hereford.

Like many people, funding and my supervisory team were key factors in my decision. Finding “medieval Frenchies” is getting more and more difficult in the UK, but Exeter is a real hub for medieval French studies, with an active weekly reading group and multiple colleagues publishing on medieval Francophone language and culture.

And, of course, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that my master’s supervisor’s glowing recommendation of Tom Hinton as “the nicest guy in the business” didn’t influence my decision a little!

As a first-year MPhil/PhD student, my days are very varied, but they all include stacks of reading. On some days, I audit postgraduate classes on medieval studies or palaeography. I also spend a lot of time drafting documents for my upgrade in May, which is essentially a formal proof of concept for my thesis. My main focus on most days is reading and translating texts for my own research, but progress is sometimes slow due to the steep learning curve.

I’m not an early riser. To help with this, I set achievable goals for the day (like reading a certain number of articles or writing a specific word count) and sometimes I even meet them! I make good use of my desk in the PGR office, with adequate breaks for office curling (ask Edward) and other enrichment activities.

The most exciting thing I have found so far comes from Walter de Bibbesworth, who tells us that flirty ladies had a habit of lisping their words to please their lovers in what is seemingly a medieval version of a vocal fry (with potentially the same problematic implications). This convention was then picked up by the friar Nicholas Bozon who used it as an example of the sins of prideful women. We then don’t see this weird quirk appear again until Chaucer, where his male friar uses the same lisping tactic to charm women.

My first piece of advice is to not be afraid to go back to basics when you’re putting together your proposal. Starting with broader themes, such as “women”, can help you narrow down a research topic that aligns better with both your interests and current research trends.

Also, try to read newer papers that have been released in the last three years or so. This will give you a sense of where your chosen research area is heading and help you to “find the gap”, ensuring your work contributes to ongoing academic discourse.

Finally, don’t be intimidated by entering a new field. Learning things as you go can help you bring fresh perspectives to the conversation, and people will be more than willing to support you if show genuine enthusiasm for your research and theirs.

Featured image: a nun reading (from Carpentras, Bibliothèque inguimbertine, MS 96 (fol. 78v).