Posted by Francis Brown

9 June 2025In an article for this month’s issue of History Today, I wrote about the way in which the discovery of a sarcophagus at Sherborne Abbey on 4 June 1925 was misidentified—certainly on very limited evidence, and possibly intentionally—as that of King Æthelberht of Wessex (d. 866), in order to generate publicity and boost support for the restoration of the abbey’s medieval Lady Chapel. This is a subject I’ve also been exploring in an exhibition and lecture series that I’ve curated at Sherborne Abbey to mark the centenary, and it’s an offshoot of my PhD research into heritage, modernity, and historical culture at Sherborne Abbey over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Based on the evidence I’ve uncovered, I’m convinced that the account I’ve offered in History Today is accurate: the discovery of a relatively unremarkable sarcophagus was hijacked in support of the Lady Chapel campaign. But something that I didn’t have enough space to get into in the magazine article, and which I’ve tried to pick apart slightly more in the exhibition and lectures, is that this was not the whole story. It cannot have been.

That is to say: in the first place, why was Æthelberht considered worth ‘rediscovering’ in the first place? And moreover, given that the ‘rediscovery’ didn’t actually succeed in precipitating game-changing support for the Lady Chapel restoration—which wasn’t completed until 1934—how and why has the story stuck for so many years? The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England barely gave the sarcophagus a second glance in 1952, noting that it was ‘probably 13th-century’ before moving on. And yet the misidentification of the sarcophagus has been repeated a number of times since, and not just in ‘popular’ literature.

In answering these questions, there’s no skirting around the fact that the 1920s were an odd time for archaeology and Anglo-Saxon history in particular. The Victorians’ long-standing fascination with the Anglo-Saxons culminated with the ‘Alfred Millenary’ of 1901 in Winchester, celebrating (roughly) a thousand years since the death of King Alfred ‘the Great’. But in the decades leading up to this event, the Anglo-Saxons had become increasingly implicated with ideas of race and ethnonationalism in popular and academic discussion, and were frequently deployed in attempts to justify British colonialism. After WWI, the association of the Anglo-Saxons as a ‘race’ with political and military strength became fraught, and inter-war invocations of King Alfred, for example, were characterised by an ambivalence over quite what the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ now meant.

Exeter’s Professor Joanne Parker has identified Robinson Jeffers’ poem, Ghosts in England (c. 1929), as representative of this ambivalence. Jeffers’ Alfred haunts the Wessex downs in confusion…

“Who are the people / And who are the enemy?” He says bewildered, / “Who are the living, who are the dead?”

And this same sense of lack, of something missing, also characterised the rediscovery of Alfred’s brother, Æthelberht, at Sherborne in 1925.

It didn’t help that no one knew who ‘King Ethelbert’ was. The press reports on the discovery were saturated with historical information about Æthelberht’s reign to fill the gap because, as The Times conceded, ‘Ethelbert hardly lives in history, and not at all in popular memory like Alfred’.

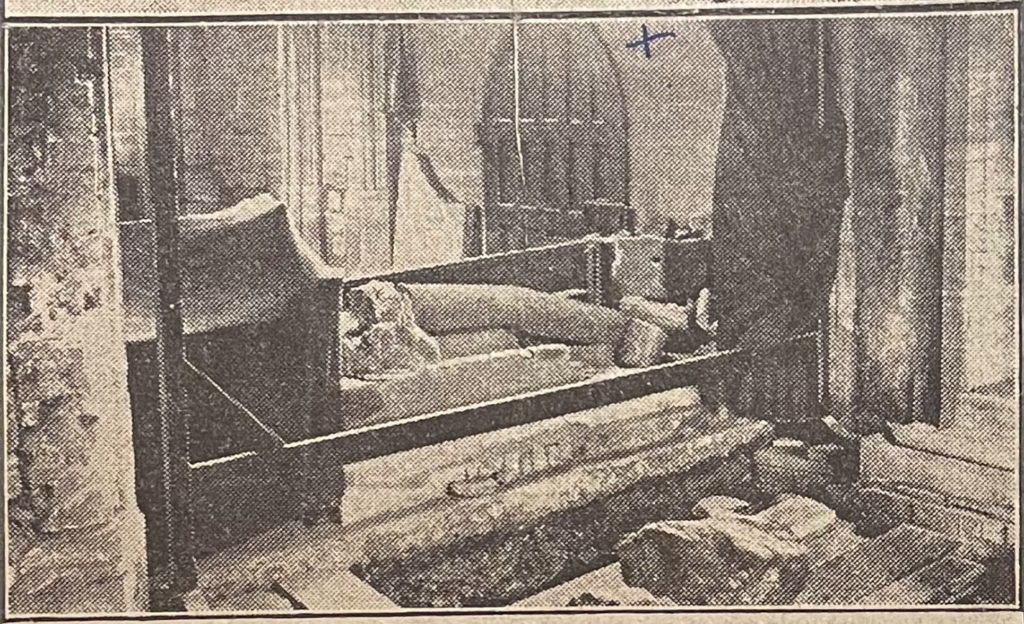

But this was ultimately a blessing in disguise, because it gave the journalists something to write about, distracting their readers’ attention from the fact that there was almost nothing to say or see of the sarcophagus itself. Unlike the rediscovery and opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922/23, which was mediated to the British public through a series of carefully-curated photographs, only one image of the find at Sherborne appeared in the press: a single, blurry photograph in The Times, which crucially, and bafflingly, doesn’t actually show the sarcophagus supposedly at the centre of it all.

Much like the medieval ship burial discovered at Sutton Hoo in 1939, which Dr Fran Allfrey has suggested first ‘[entered] the public arena as a lack, a hole in the ground, an obscured landscape’, Æthelberht similarly made his way into the popular consciousness as an absence. However, unlike the find at Sutton Hoo, which was politicised along ethnonationalist lines amid the outbreak of WWII, the re-discovery of Æthelberht is striking for how little it was interpreted in this way.

Indeed, the endurance of the misidentification over the following decades may have been partly down to this precise lack of willingness to question the discovery at the time, to think too much about Æthelberht, and to try to fill the emptiness at the centre of the find.

As I’ve been researching and writing about this subject over the last year, I’ve returned several times to another interwar poem, written about Sherborne in the early 1920s by a ‘C. M. M.’ and published in a pamphlet advertising the Lady Chapel restoration. I keep coming back to it, mainly, because I’m frustrated with my inability to make very much of it.

A few lines about the abbey run…

‘The preacher’s voice re-echoes down the nave / Bringing to mind those other far off calls / Which have resounded in this sacred place, / Year after year, for centuries complete’

And so on.

It’s fair to say that it stands unfavourably next to Jeffers’ poem. The content is banal, and the language is uninspired. But, whether intentionally or not—in fact, possibly because of this—it seems to testify to the same confusion over, and reticence to really consider, what certain areas of the past meant in 1925.

All of this perhaps goes some way to explaining why it was relatively easy to misidentify the sarcophagus, and to sell the story as a means to revive interest in the Lady Chapel restoration.

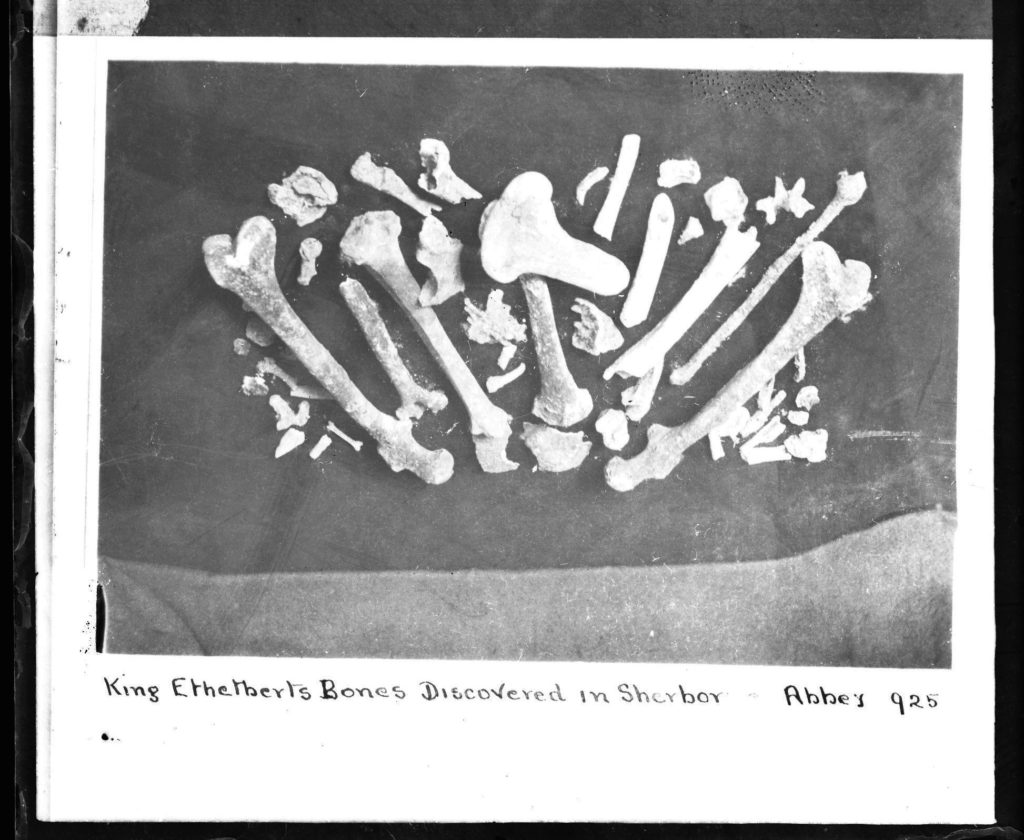

And yet, at least one person was thinking about what the rediscovery of Æthelberht meant. The photo published in the Times isn’t the only one documenting the 1925 find that survives – it’s one of two. The other was never published, and was stumbled across only a few years ago in the abbey library as a glass-plate slide. It shows the bones that the sarcophagus contained laid out on a black background and lit from above, as if for examination, with the caption ‘King Ethelberts Bones Discovered in Sherborne Abbey 1925’ scrawled across the bottom. Beyond this, we know nothing about the photograph, including when or why it was taken – no record of an official examination ever taking place survives.

For me, this photo is both the most fascinating and the most perplexing part of the story, which it seems to disrupt. The circumstances in which it was taken might come to light one day. But for now, it tumbles disembodied through space and time, as seemingly lost and questioning as Alfred and Æthelberht were in the 1920s.

Francis Brown is a PhD student at Exeter. ‘The Kings of Wessex Remembered’ exhibition and lecture series runs 2–29 June 2025 in Sherborne Abbey. Francis’s article about the supposed rediscovery of King Æthelbert, ‘A Skeleton in the Chapel’, is published in the June 2025 issue of History Today.