Posted by Elliot Kendall

29 September 2025Elliot Kendall is Associate Professor in Medieval and Early Modern Literature, and is particularly interested in how non-traditional approaches (such as anthropology) can help us to understand and interpret pre-modern literary material. As he explains in this week’s post, he also loves a good footnote …

While burrowing into research, we sometimes uncover connections that are fascinating but remain a long way from our main business. If we’re lucky, a footnote can salute the intrigue; can acknowledge a path untunnelled.

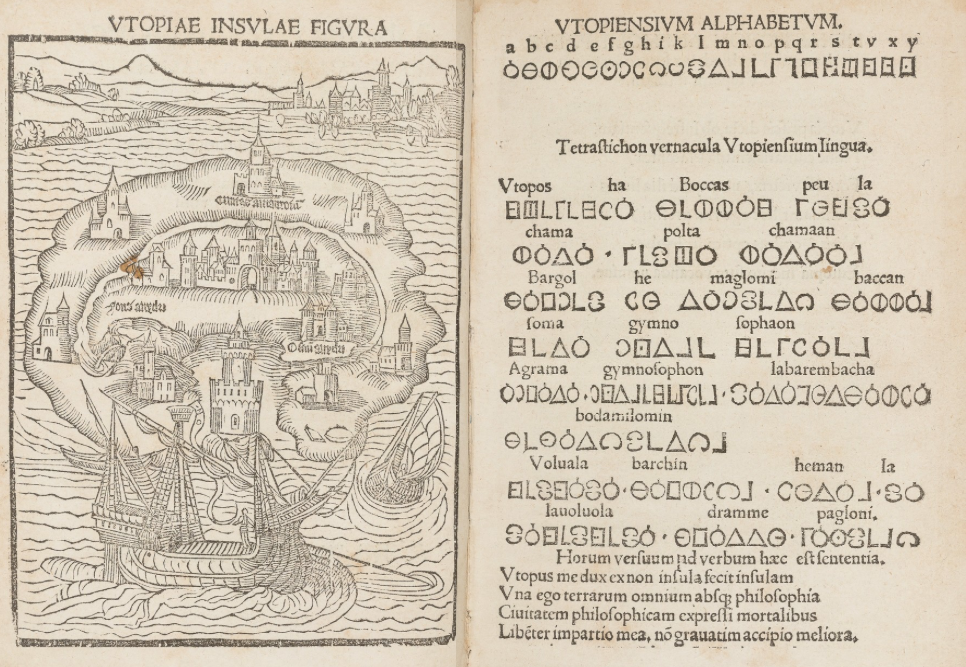

I had this experience recently while writing about Thomas More’s Utopia. When More’s traveller Hythloday transports a selection of Greek and Latin texts to Utopia, a monkey rips up parts of Theophrastus on plants (presumably, based on early modern printings, a volume containing both Aristotle’s contemporary’s Enquiry into Plants and Causes of Plants).

The monkey’s disruptiveness sets Theophrastus up as a counterpoint to Utopia in ways that needn’t detain us here, but one chapter in the Enquiry Into Plants snagged my attention. It discusses kings of Cyprus (who leave their island’s trees undisturbed) and ends with some observations about Monte Circeo, a high promontory (headland) on the west coast of Italy about half way between Rome and Naples.

Theophrastus notes that residents of Monte Circeo advertise it as the home of Circe and show off Elpenor’s tomb:

Further it is said that the district is a recent addition to the land, and that once this piece of land was an island, but now the sea has been silted up by certain streams and it has become united to the coast.

(Enquiry, tr. Arthur Hort, 5.8.3)

The chapter caught my attention because of the curious way it mirrors events in Utopia: unlike the kings of Cyprus, the Utopians transplant a wood, rather than leaving it alone. Utopia itself used to be a promontory and is now an island, dug away from the mainland by its conqueror-founder, King Utopus. Tempted as I was to decide that More derived both Utopus’s geoengineering and the Utopians’ relocation of a wood from Theophrastus, I thought I should check whether the report of silting was anything more than an expedient way of reconciling fourth-century BCE geography with Homer’s.

Monte Circeo was, in fact, once an island, but not recently. The promontory comprises a Miocene thrust — a bulge of Jurassic rock raised by tectonic activity in the Apennine-Tyrrhenian basin — surrounded by Pliocene coastal sediments. ‘Circe’s’ island had in fact become a promontory several million years before Theophrastus was born. On top of this, literally, a Bronze Age Somma-Vesuvius pumice eruption and massive sedimentary deposits in the millennium before Theophrastus’s time had increased the land area of the Agro Pontino north of Monte Circeo.

It is plausible, then, that Theophrastus in the Enquiry is reporting a centuries-old silting up that occurred on the Tyrrhenian coast, but mistakenly linking it to Monte Circeo itself. In any case, he is correct, but on a geological technicality: the sedimentary joining of the ‘island’ to the ‘coast’ had occurred long before our species evolved. Or were locals in antiquity just trying to explain the conspicuous difference between the Jurassic stone of their mountain and the rest of the promontory?

None of this affects my reading of Utopia. It does, however, remind me that it is easy to dismiss all possibility of mythic or far-fetched narratives and tropes having factual underpinnings, even as geologists, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historical linguists increasingly present reasons not to do so. Thanks to the raw materials that they unearth, we can see that what seemed to be pure textual invention is textual transformation, or that their materials rhyme with textuality though the facts couldn’t (fully) have been known. And that made for a pleasing footnote.

Header image: View from Monte Circeo today, looking north-west towards Sabaudia (Shutterstock).