Posted by sd618

17 November 2025This week sees the return of our ‘research postcards’ series, as Sean Doherty and Clem Pursey, armed only with an eraser, enter the hallowed halls of Eton College in search of the Apocalypse — and, along the way, some medieval French.

It seems fitting that a project concerned with language learning should finally visit a school — though with its 2,300-acre campus, complete with three museums, a rifle range, and a rowing lake, Eton College is not exactly what you might call a typical establishment.

In late July 2025, Clementine Pursey and I made the journey to Eton to examine a manuscript for our research on the Learning Anglo-French project. Much like arriving at an Oxbridge college, we entered through the gatehouse and reported to the porter’s lodge, from where we were collected by the librarian and led towards the library that sits at the heart of the school. As we passed through the cloisters and corridors, it was reassuring to see that not even Eton has escaped the schoolboy’s instinct for graffiti —though the names were carved with a serifed elegance in keeping with the surroundings.

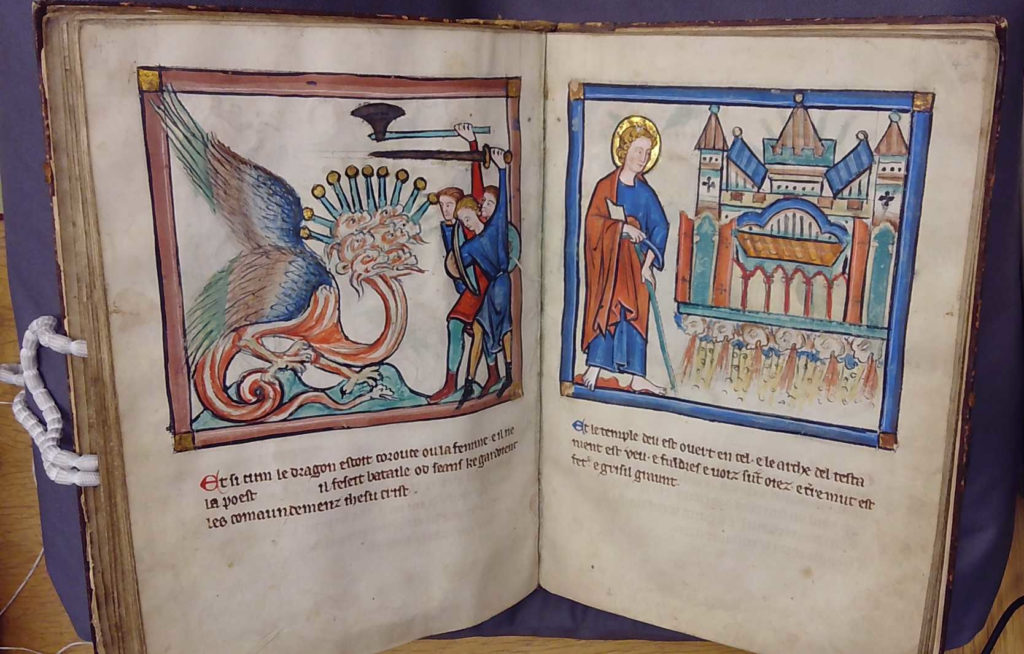

In the library we found the manuscript we had come to see: MS 177, one of the highlights of the College’s collection of around 200 medieval and Renaissance volumes. The late thirteenth-century manuscript is formed of two parts. Part I, commonly referred to as the ‘Eton Roundels’, contains twelve full-page illustrations juxtaposing Old Testament scenes with their New Testament fulfilments. Part II, an illuminated Apocalypse, contains ninety-eight depictions of scenes from the Book of Revelation, accompanied by Anglo-Norman (French) captions and later glosses in English and Latin.

We were there to carry out a ‘biocodicological’ study of the manuscript, with the aim of identifying the species of animal skins used in its production, and investigating the individuals who may have used it in their education. The initial process involves gently rubbing a plastic eraser across the surface of the parchment to collect microscopic collagen fibres that adhere to the eraser crumbs. This sampling was undertaken by a member of the College’s conservation team to ensure that the manuscript remained entirely unharmed.

Back in the laboratory, these samples will be analysed to determine whether sheep, goat, or calfskin parchment was used. We also hope to recover traces of human DNA, which may provide insight into the genetic sex of those who once handled the manuscript. Such evidence could contribute to our understanding of patterns of readership in the medieval period, particularly the extent of female engagement with manuscripts of this kind. Identifying this contact has, until now, been difficult to prove without visible signatures or dedications. If this technique yields the results that we hope, they will expose an entirely new corpus of materials for the study of women’s language learning in England – an exciting prospect for the LAF team.

To study a thirteenth-century manuscript used for religious and linguistic instruction within the walls of one of England’s most storied schools was a great privilege. As our analyses progress, we hope that the microscopic traces preserved on MS 177 will bring new, and perhaps unexpected, voices into the history of medieval education.