Posted by Helen Birkett

6 December 2017In my PhD research, I am looking at the local pasts that were communicated through liturgy in the tenth century in a metropolitan city on the Moselle river: Trier. My main corpus of sources consists of prayers, sermons, hymns and hagiographical texts, all of which can be found in medieval manuscripts from this area. In order to study these manuscripts, I needed to visit Trier itself, as they were not digitized yet. Visiting the epicentre of my research, however, proved more fruitful than I had imagined.

Architecturally, the city of Trier is a strange mix of every period from the last two millennia. The Porta Nigra and a basilica from the time of Constantine the Great represent the Roman past, the cathedral and market square represent the High Middle Ages, and numerous churches and monasteries in and around the city were rebuilt in the course of history. The city breathes its own past on every corner. It was very useful to be inside my ‘object of study’ for many reasons, not least for its insights into the local religious communities of tenth-century Trier.

Firstly, I could physically measure the distance between the religious centres of the city. Even though many churches and monasteries have changed considerably over the last thousand years, the location of these centres did not. Being able to walk from the (still-in-use) monastic centre of St. Eucharius to the cathedral in half an hour, and then going another ten minutes to the royal abbey of St. Maximin and the canonical centre of St. Paulin, I got a clear grasp of how close these centres were to each other. This would have made interaction between the different centres very likely.

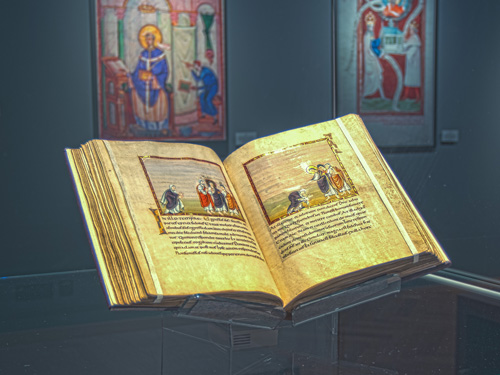

Another advantage of being at the ‘crime scene’ of my research is the availability of material culture. Studying liturgical sources, I was delighted to go into the Dom Schatzkammer, where golden reliquaries just sat there, waiting to be studied. Another obligatory visit was, of course, to the Stadtbibliothek, a modern building where the medieval manuscripts are kept. After having had a look at the beautifully illuminated Ottonian manuscripts – a local guide was very keen on explaining their greatness – I got to see my original incentive for visiting Trier.

Not only the artefacts and manuscripts, but also the lay-out of churches and monasteries were enlightening. Most of the time that is… Most bizarre was my visit to the royal abbey of St. Maximin. This monastery had been enormous and thriving in the tenth century. Now, however, most of the monastic buildings are gone, and the church itself – rebuilt in the seventeenth century – functions as a gym for the local secondary school. Gym mattresses were protecting the students from painfully bumping into the massive columns of the nave, and a basketball net had replaced a statue of Christ in front of the apse.

Although in some cases, time had completely ruined the medieval ambiance, other places seem to have survived the test of time brilliantly. A large component of my research comprises the study of local patron saints, as hagiographical texts and prayers for these saints can tell us about the importance of that local saint and the role he or she played in local society. Visiting the burial places – the centres of local cults – was an important element of my stay in Trier. Entering the crypt of St. Matthias’s Abbey, and sitting down in front of the late antique sarcophagi of the first archbishop of Trier, Eucharius, and his successor, Valerius, I could not help feeling connected with all those monks and pilgrims who have been visiting this crypt to pray to the local patron for the past sixteen centuries. The feast of St. Eucharius is still celebrated by the local Benedictine community every December: continuity in its highest form.

Studying medieval history is not only studying primary sources and reading literature. Most importantly, it is an attempt at imagining a past society. This society is best understood, I believe, if you have a chance to be part of it. When I returned from my visit to Trier, I did not only bring home notes on the studied manuscripts and reliquaries, but also about the physical distance between different centres, and the ambiance of local cult sites. And, in the spirit of traveling medieval monks, I brought back the thought that – if nothing else – I will have saint Eucharius of Trier at my side on the rest of my intellectual journey.

Lenneke van Raajj, PhD Student on the HERA-funded After Empire project