Posted by James Gordon Clark

20 June 2022This is the season of Saint Alban. The feast-day falls on 22 June. Medieval England knew him as their ‘protomartyr’, that is the first of all their Christian people to face death in defence of their faith. They spoke of Alban as an alter Stephen, the first in all the Church’s history to be put to death purely because they were a follower of Christ.

According to a legend whose main features were settled by the end of the twelfth century, Alban was a prominent citizen of the Roman city of Verulamium. He was converted to the new cause of Christianity when he sheltered a travelling priest trying to escape the persecution of the pagan authorities. Soon discovered, Alban was condemned to suffer the same mortal punishment that awaited the priest unless he threw off his new faith. He refused and was executed with his priest mentor, on a hillside outside the city’s walls.

His cult enjoyed an exceptionally long, if not quite continuous history: it was first witnessed around the third decade of the fifth century by the missionary bishop, Germanus of Auxerre (c.378-442×448 CE); the shrine containing the principal relics still attracted donations from the town of St Albans in reign of Henry VIII eleven centuries later. The cult was also carried beyond England to Cologne and Odense, aided by the reach of relics – or at least objects alleged to be relics – taken from the original shrine. The feast-day was among those of the earliest saints of England – Cuthbert, Edmund, Edward the Confessor – to be recognised in the calendar of the Sarum rite which became the most widely followed in England between the Black Death and the Break with Rome.

The antiquity and celebrity of Alban, protomartyr of England, were acknowledged but often he seemed to be eclipsed as a saint for the nation by the pre-Conquest figures who also featured in the calendar of Sarum. In particular, his cult struggled to capture the devout attentions of the English monarchy. Of course, although he was adopted as a saint for England, his own history was rooted in Roman Britain, a time long before the formative years of English kingship. By legend Alban’s relics had been rediscovered by Offa of Mercia (reigned 757-96 CE) who built a basilica to house them. But it had not been the beginning of a lasting tie to the crown. From the Normans to the first of the Tudors, Cuthbert, Edmund and Edward the Confessor never lost their place of priority in the public devotions of royalty. For the custodians of Alban’s relics, the monks of the Benedictine abbey established close by his Roman city, it appeared that even the passing attention of the reigning royal family was always hard-won.

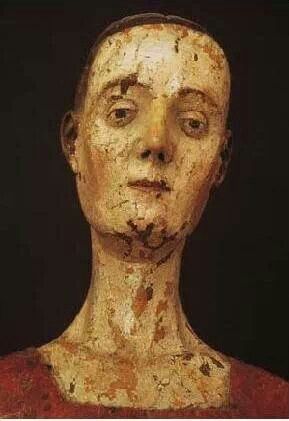

After a slow start, the monks did invest in the fabric of the protomartyr’s shrine. Apparently by the Tudor period it even boasted a mechanical statue which, operated like a giant marionette, could be made to bow to pilgrims.

But above all, to raise the profile of their saint the monks exploited their best asset, their almost unrivalled skills in original writing and the production of books. From the 1170s they transformed the written records of the saint and his cult: new lives of Alban and his co-martyr were composed in prose and verse and a collection was compiled of the reports of miracles witnessed at the shrine. After a forced interruption in the First Barons’ War (1215-17), and an ambitious re-development of the abbey church, their efforts were continued from the end of the 1230s, just as the king, Henry III (1216-72), began his personal rule.

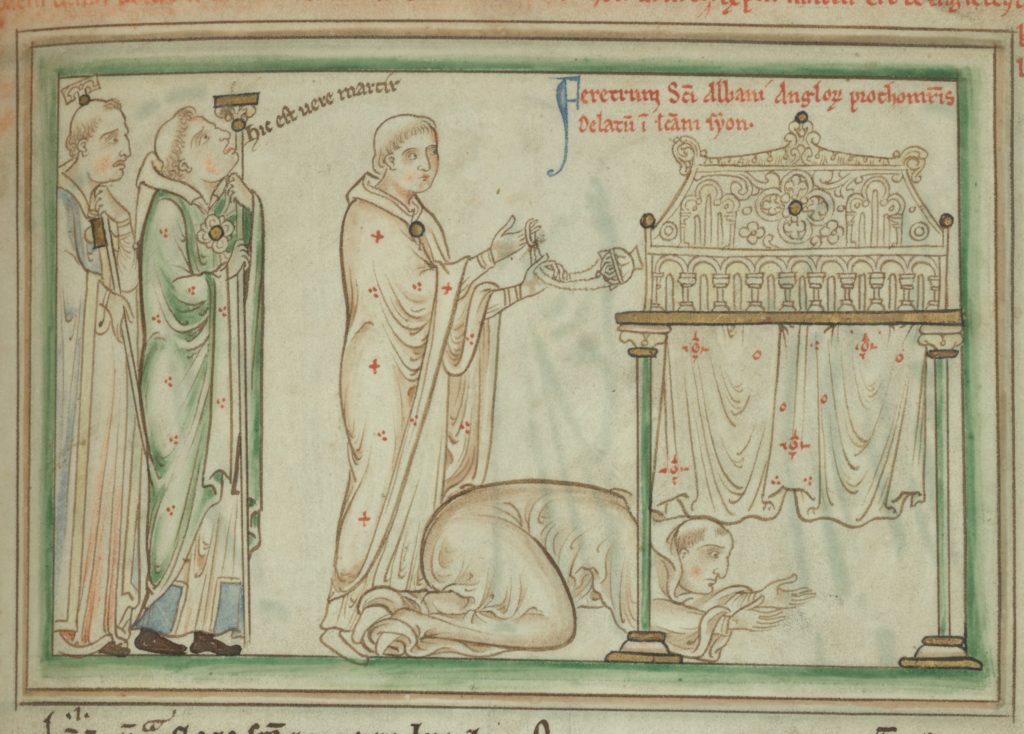

Now, the greatest of all of the abbey’s book craftsmen, Matthew Paris (d. c. 1259) made a beautiful anthology of Alban-alia, bringing together both versions of the saints’ lives in Latin together with another in French verse which is generally thought to be by Matthew himself. He accompanied the French poem with a sequence of fifty-four painted panels which filled the top half of each page.

From the outset, there can be no doubt that the book was meant to be in the sight-line of those outside the community of monks.

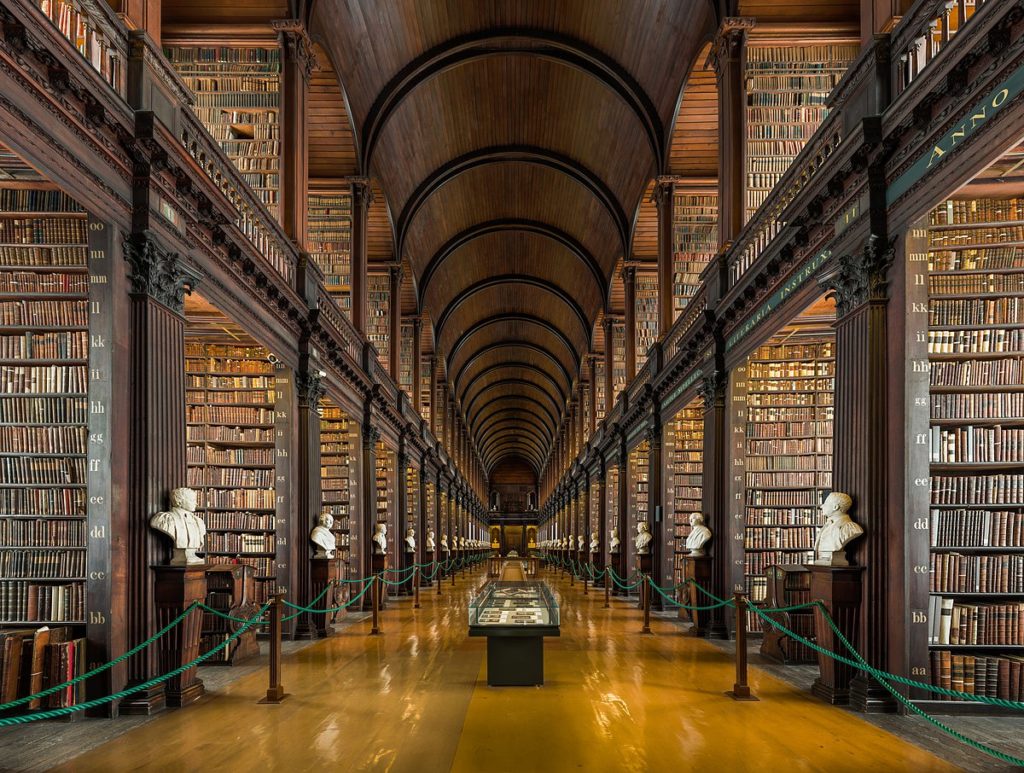

This week, this remarkable manuscript, which has become known as the ‘Book of St Albans’, will be fully and freely accessible in a high-resolution digital copy thanks to the efforts of its’ custodians, the library of Trinity College, Dublin. A virtual exhibition is also showing on Google Arts & Culture.

When the ‘Book of St Alban’ was first made there were promising signs of rising royal interest in Alban and his shrine. Matthew Paris himself in the contemporary history called Chronica maiora recorded a succession of royal visits, first, in 1240, Richard, earl of Cornwall (1209-72), the king’s brother, on route for Crusade, and then of King Henry himself. In 1244 Henry III visited on 11 June, just eleven days ahead of the feast, and he returned to the abbey six months later, on 21 December. In September 1247 Matthew proudly recorded that the king had made a special appeal to the monks to pray for the recovery from illness of his eldest son, Prince Edward (b. 1239), the future king. Henry III returned to St Albans in September 1251 and made unspecified offerings at the shrine. He came again in August 1252, then in the company of Prince Edward and presented a robe, two necklaces, two gold rings and twelve gold coins. From 1255 to 1258 Henry came each year, twice in Lent, then in August and November. On each occasion he adorned the shrine of Alban and his co-martyr with new decorations, textiles and jewels.

The monks surely felt a certain pique that in spite of their attentions, still the royal family did not come to the St Albans on the feast-day itself, 22 June. Even Matthew Paris’ beautiful book could not distract them completely from the attractions of other cults and their shrines. In his Chronica maiora Matthew noted the lively activity now stirring at monasteries and cathedrals across the kingdom. Thomas Becket’s relics at Canterbury had been re-set after the years of war; there were new cults associated with contemporary churchmen – Richard of Chichester, Edmund of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. Matthew himself gathered news of them in the hope that his own church might catch hold of their proverbial coat tails. But the fickle favour of patrons was obvious even in the ‘Book of St Alban’ itself. There is a faint note recording that the texts of two other saints’ lives – Edward the Confessor and Thomas Becket – had been shared with a noblewoman, apparently Isabel de Warenne, countess of Arundel; a bitter irony for Matthew Paris that it should be noted in the book he made to proclaim the protomartyr’s primacy. Alban’s rivals showed no signs of retreating.

The monks’ courting of the crown continued undeterred. Henry III’s grandson, Edward II, came to St Albans at Palmtide 1314. When, later in the fourteenth century, the monks created a confraternity in honour of St Albans, the wider royal family and the courtier nobility came in large groups to be inducted as members. These ceremonies are recorded in the abbey’s first surviving book of benefactors (now British Library MS Nero D VII). The last of the Plantagenets, Edward III, and his grandson, Richard II, were claimed by the monks as generous patrons to their church, although the only record of a visit by either, is of King Richard in the wake of the Peasants’ Revolt (1381), when he witnessed the execution of the rebellion’s priest provocateur, John Balle (15 July). The monks also commended the first of the Lancastrian monarchs, Henry IV and Henry V, but again there is no account of their visits. Their dowager queens, Joan de Navarre and Catherine de Valois did come to the shrine, the former just days before the feast of the martyr in 1427, the latter, after Easter 1428. Henry V’s youngest brother, Humfrey, duke of Gloucester (1390-1447) and his wife, Eleanor Cobham, made their devotions at the shrine around the octave of the feast in 1431.

And then, finally, in 1458, two hundred years after the last of Henry III’s series of visits, the king himself, Henry VI came to St Albans to keep the feast. He arrived at the abbey on 20 June and stayed for six days. In fact, this was the king’s second visit in scarcely two months.

It may have been at the earlier visit in April that he was shown Matthew Paris’ ‘Book of St Albans’. A memorandum on the lower margin of fo. 1v notes that it was seen by the king on his departure from a meeting of his Great Council in Westminster, which had been convened in February.