Posted by Thomas Hinton

1 July 2024Thomas Hinton is Associate Professor of French Language and Literature, and Principal Investigator on a newly-launched five-year research project. In this post, part of our ‘Research Postcards’ series, he shares his reflections on a research trip with an altogether different set of aims …

In late May, Sean Doherty and I made a trip to the Wren Library at Trinity College Cambridge to take samples from three manuscripts as part of initial work for the Learning Anglo-French (LAF) project. This project studies the manuscripts used for learning French in medieval Britain, with two chief aims: to better understand who was teaching and learning French, how and why; and to explore how interdisciplinary collaboration and the integration of different methodologies can generate new insights into medieval manuscript culture. One methodology that speaks to both aims is biocodicology – the biological study of manuscripts – and this is where Sean’s expertise is crucial. For his PhD, Sean analysed the proteins in parchment to look for patterns in the species distribution for certain types of document, and he will be doing similar analysis on the manuscripts relevant to LAF. We are also going to try something quite new: by gathering human DNA from users of the manuscripts and analysing the balance of XX and XY chromosomes, we hope to find out about the hands-on involvement of women and girls in the types of learning environment which included the teaching of French: legal, administrative and business training; religious houses; and aristocratic households. One of the significant challenges here will be working out how to differentiate medieval user traces from those left by more recent handling, for instance by librarians or researchers.

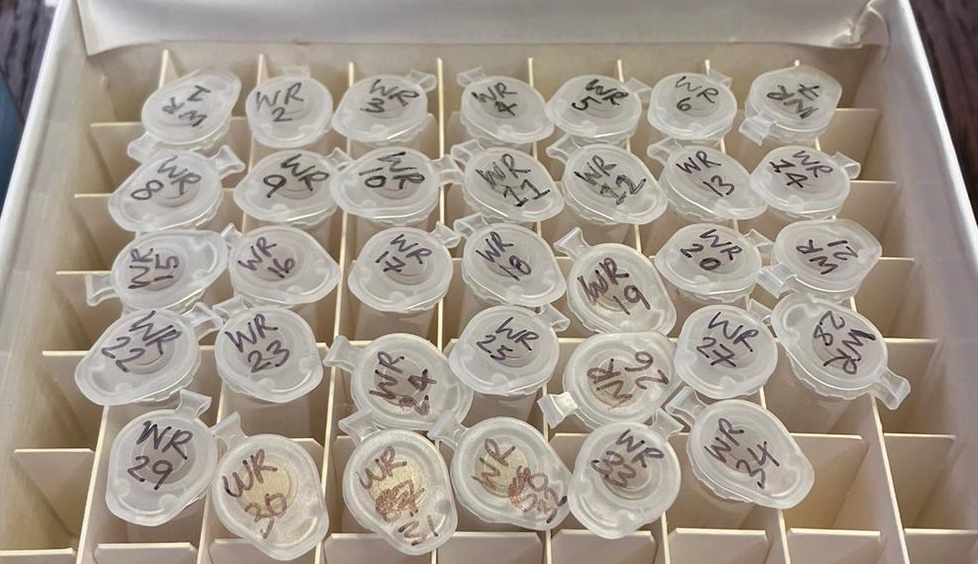

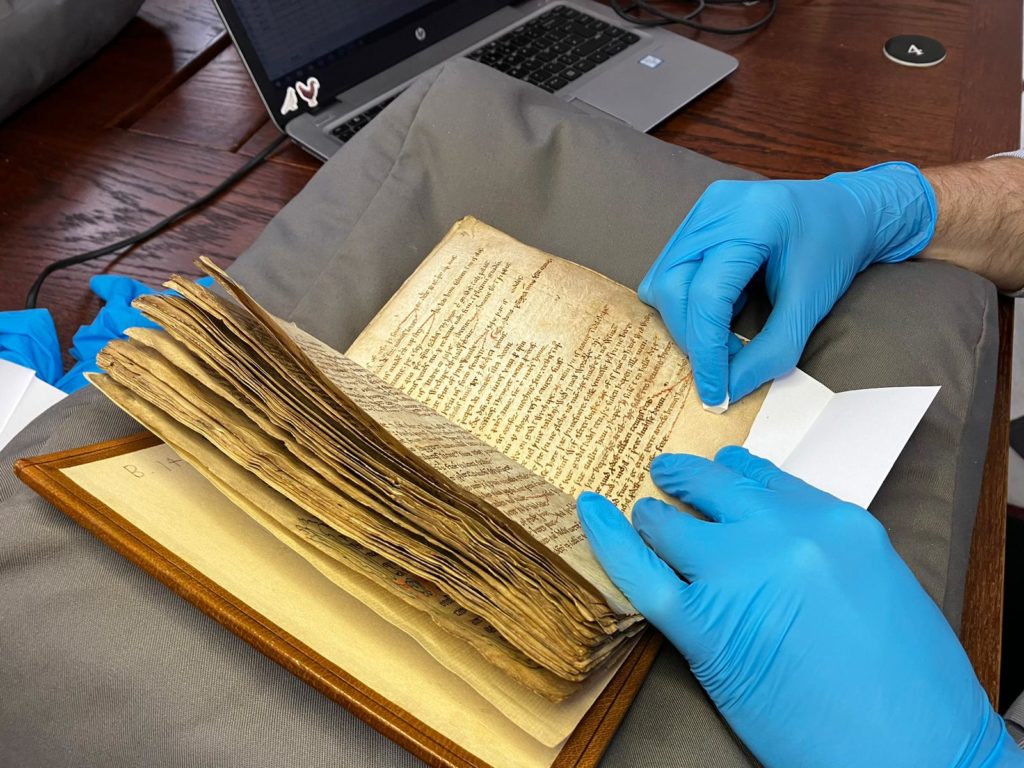

At the Wren Library we were very kindly hosted by Nicolas Bell and Anne McLaughlin, and we have benefitted greatly from their enthusiasm in working with us on this initial sampling, which will allow us to generate a first round of data and test and refine our methodology. Good communication and a relationship of trust with librarians and curators is a key part of any such endeavour. On a personal level, this was my first experience of biocodicological sampling. I watched as Sean gently rubbed an eraser across small areas of the manuscript surface; the crumbs shed by the eraser on contact with the parchment picked up cellular material from the skin, which Sean collected into a small plastic tube. Between the patience needed to generate sufficient crumbs and the rigour required in properly labelling and documenting each sample, it soon became apparent that this is not an activity for the hasty.

Once I had had a good while to observe the process, I was delighted to try my own hand at sampling a few pages of Cambridge, Trinity College, MS B.14.40, the only known copy of a late-medieval text called Femina largely derived from Walter de Bibbesworth’s Tretiz. I don’t know if it was something about the surgical gloves I was wearing, or the repetitive process of brushing the eraser across the page, but I found my relationship to the manuscript to be quite different from my usual experience in reading rooms, where my focus is almost always on the texts set out on the page. Unexpectedly, it put me in mind of how the medieval artisans who prepared parchment, wrote texts, and decorated the pages, must have related to the products of their craft: as material objects first and foremost. At the same time, deciding where to sample in order to generate as much human DNA as possible – to allow us to explore the feasibility of isolating medieval user data – involved trying to imagine those medieval users touching parts of the page: holding the corner of the book between thumb and forefinger, or tapping their finger against the end of a line. In such moments of reflection on historic usage, the relationship between human and animal, text and support, medium and message, is brought to the fore in all its glorious messiness. The challenge for LAF, as we head back to Exeter with our tubes containing precious eraser crumbs, is to see how far we can succeed in disentangling some of that messiness – and, if so, what new understandings will be revealed.