Posted by Edward Mills

18 November 2024There aren’t many archives where you can have a go on a Rockin’ Rhino ride during your lunch break, but then again, there are many reasons why Longleat House isn’t your typical archive.

Longleat itself has a fascinating history. The site itself had been an Augustinian priory before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, after which it was granted to Sir John Thynne. Thynne’s work in building the great house (completed around 1580, and still standing today) led to it becoming known as one of the first so-called Elizabethan ‘prodigy houses‘ — a deliberately ostentatious design that served as much to demonstrate power and prestige as it did to provide a comfortable seat for a noble. Indeed, John Thynne’s descendants, the present-day Marquesses of Bath, still live on the site today.

For most people, though, Longleat is best known as an attraction. The Marquesses invested heavily in the estate’s commercial elements after the Second World War, and the mid-1960s saw the opening of the first drive-through safari park outside of Africa, which attracts thousands of visitors each year (many of whom have their focus resolutely set on the monkeys and lions, rather than on the ancestral seat of a member of the landed gentry). Thanks to the safari park — and the enormous Center Parcs next door — the area around the house itself is now a curious mix of stately home and theme park, with the hedge-maze and gift-shop jostling for space with doughnut stands, the Adventure Castle, and the aforementioned rhino mini-coaster.

The busy schedule of events — including the upcoming Festival of Light — meant that my visit to the archives at Longleat has been somewhat time-limited, with the archive on the cusp of closing for the winter period. I’ve been at Longleat under the auspices of the Learning Anglo-French project, exploring their holdings with a view to shedding light on how, where, and why the French language was learned and taught in later medieval Britain. Family collections such as those of the Marquesses of Bath have long been thought of as potential goldmines for this sort of work, since they’ve tended to receive less support (and much less publicity) than major national or institutional collections such as the Bodleian or British Libraries.

As much as the house might appear intimidating, getting into the Library and Archives itself was a very straightforward process. From the outset, it was clear that the team at Longleat care deeply about sharing their fascinating holdings, and a helpful email exchange set me on the right track: with entry to the site secured, I was instructed to make my way to the back entrance, ringing the bell for ‘tradesmen and deliveries’. From there, I was ushered upstairs to the reading room itself.

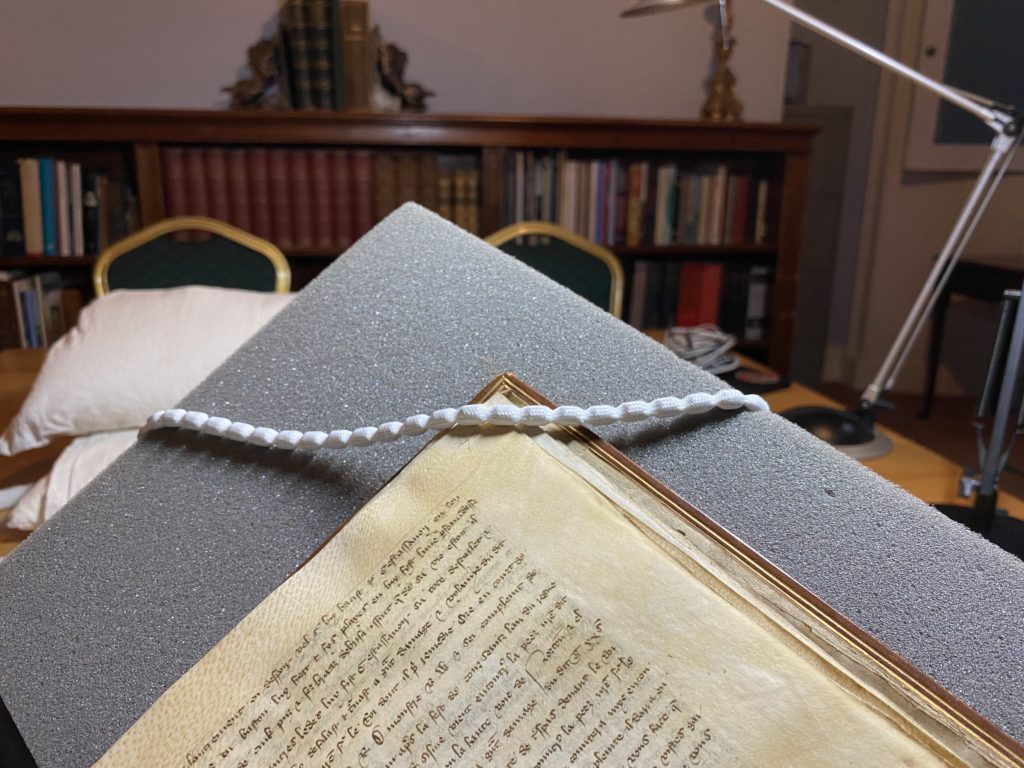

Once there, the experience was in many ways similar to that of any other manuscripts reading room, with all of the standard rules: clean hands, pencils only, and careful handling of the material were all mandatory. The ‘condition checks’ on material (made assiduously by Edwina, the librarian), also imposed necessary constraints on how it could be handled: one volume, for instance, couldn’t be opened more than 90 degrees.

Stepping outside of major national institutions, and into a much smaller reading room where the team and I could enthusiastically share our interests, reminded me just how important a role archivists, librarians, and rare books specialists play in our work as medievalists. In 2018, Bridget Whearty devised the Caswell Test (modelled after the famous Bechdel Test for assessing how women are depicted in film), which challenges medievalists to look beyond vague invocations of ‘the archive’. Instead, Whearty argues, we must engage with, value, and (crucially) cite the people — library, archive, and information professionals — who have historically been visible only in thank-you notes and acknowledgements.

The team at Longleat are experts in the material that they preserve, as attested to by the enormous files of correspondence, citations, and catalogue descriptions that accompany many of the manuscripts, and I’m determined to make all of this abundantly clear as and when I’m able to publish my own work through Learning Anglo-French. Warminster, Longleat House, MS 37 didn’t just spring fully-formed into the lap of Ivor Arnold in 1937, and since then, generations of professionals have laboured — often invisibly — to keep materials like it available and accessible. A single note in the on-site catalogue (in the hand of a previous librarian) clarified at a stroke the content of a text in MS 37 that, to the best of my knowledge, had only ever been described in abstract terms; the existence of this invaluable, under-the-radar work is something that we’d all do well to remember. Their work might not be as visible as that of researchers in English, History, or Modern Languages departments — or, for that matter, as that of the somewhat-baffled attendant on the Rockin’ Rhino ride when I walked up to it — but it’s every bit as crucial to our discipline.

Longleat Library and Archives is open between 1st April and 31st October each year. For enquiries, contact archives@longleat.co.uk.