Posted by David McLean

26 May 2025We’re staying with our ‘spotlight’ series this week, as we once again hear from one of the Centre’s many PhD students. David McLean is working on his doctorate in the Department of Archaeology and History, and took some time — fresh from delivering a lecture for the Devon History Society — to share some of his work with us.

I’m working on a regional comparison of how late medieval monasteries managed their manors, and of how the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century impacted them.

I lived in Blackawton for a number of years, which (quite apart from its evident medieval character) had precisely one of those ‘monastic manors’. Contrary to their reputation as isolated institutions, religious foundations were often deeply rooted in their local communities, and frequently came into the possession of manor-houses and other holdings; the manor at Blackawton had been given to Torre Abbey in the 13th century. This raised a subsequent question: what happened to these manors (and their tenants) when their monastic owners suddenly vanished?

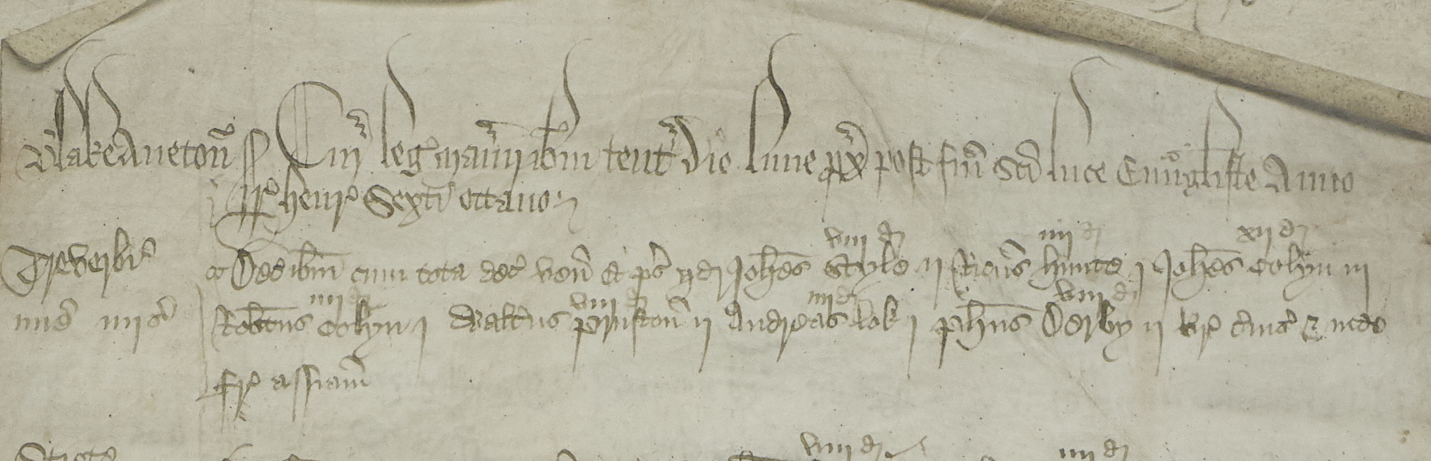

Many of my key primary sources are increasingly being digitised, which makes the leg-work of archival research a great deal easier! I’ve been spending a lot of time with the cartularies (collections of charters) belonging to Torre Abbey and Dunfermline Abbey. Many of the more obscure sources, though, still require in-person archive visits, and I’ve been fortunate to work with monastic accounts held at the Devon Heritage Centre (such as the one for Blackawton at the top of this post), as well as the (in)famous 1535 Valor Ecclesiasticus (used to assess the holdings of monasteries prior to the Dissolution).

I did the Masters in Medieval Studies at Exeter because it was close to where I was then living and Exeter had a good reputation for Medieval Studies. By the time I was considering pursuing a doctoral degree, I had relocated to Edinburgh. The expertise provided by Professor James Clark in the field of dissolution significantly outweighed any concerns regarding distance. Additionally, having completed my MA during the pandemic, I was well-acquainted with online learning. Furthermore, my research topic requires visits to various archives throughout the UK, making Edinburgh a good strategic base of operations.

Most days, I’m at my desk by 8am. This is when I tend to get most of my writing done, so after a couple of hours — once my writing brain is hurting — I move on to something else. Typically, this is when I find myself looking at new sources, or perhaps creating maps and images.

I’ve been surprised by the amount of wealth that some monastic tenants appear to have acquired! Blackawton provides another good example here: the image below shows members of the Fordes (a family of around forty tenants in 1588), dressed in their finery. 1588 is of course five decades post-Dissolution, but the family was well-established before this point.

There’s plenty of advice out there to help you succeed with the academic side of a PhD, but I’d add one other point: do make sure that you take care of your health, especially mature students. You’ll likely be spending a lot of time sitting at a desk, so take the time to move around regularly.

Featured image: detail from the manor court-roll of Blackawton, 1429-1430. Devon Heritage Centre, CR/20001.