Posted by Edward Mills

16 June 2025Avid followers of the Centre’s web presence (both of you) will have noticed that the Centre is now on Instagram (under the handle @ExeterMedieval). As we start this new venture, it would be remiss of us not to look back on the history of social media for medievalists: this week, Edward Mills reflects on the changing fortunes of one such platform.

Social media is a popular subject in the blogosphere. Our very own Levi Roach offered his own top tips on the topic five years ago, all of which have undoubtedly stood the test of time. That said, five years is a very long time on the internet, and since the heady days of May 2020 (!), medievalists who are active in the online sphere have had to contend with several major changes. Perhaps the most unexpected of these is the purchase of Twitter by Elon Musk, the subsequent exodus of many of the active medievalists who used it it, and the awkward persistence of the original site’s zombie corpse under the new incarnation, ‘X’.

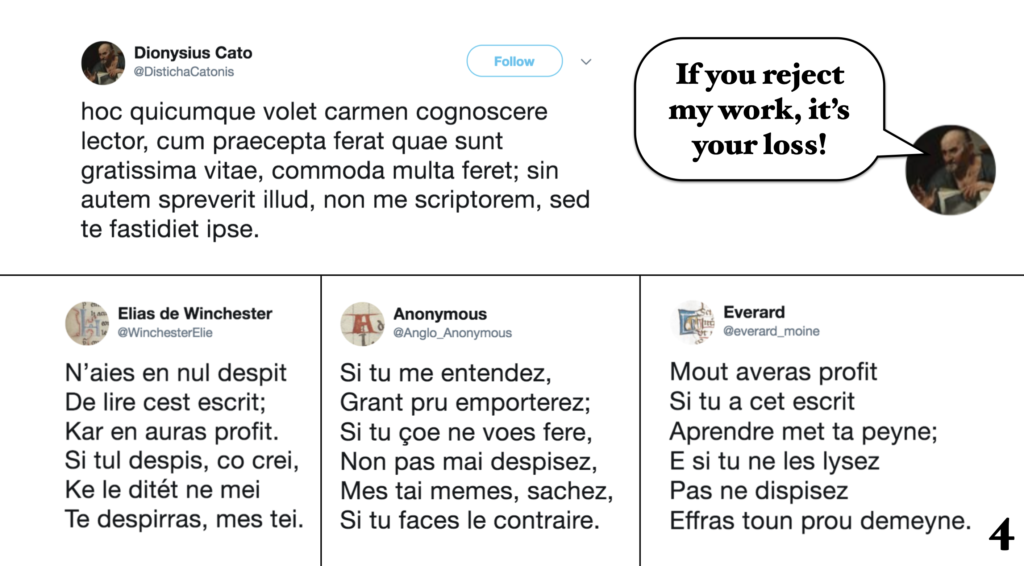

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately as I’ve been reading Alicia Spencer-Hall’s new book, Medieval Twitter (from which — full disclosure — the phrase ‘Twitter’s zombie corpse’ has been wholeheartedly pilfered). Alicia’s book has been a long time in the making, and news of their work was exciting back in 2018, as those of us who were active on #MedievalTwitter were gleefully experimenting with the potential that the platform had. We created threads, conference hashtags, and — on occasion — whole new Twitter accounts. I was an enthusiastic Tweeter myself, and leant into its potential as a storytelling tool: a 2018 conference paper saw me comparing three different translations of the Disticha Catonis (a collection of pithy moral sayings popular in medieval Europe) by attributing each one to a different Twitter handle.

Nowadays, experiments like this look almost quaint, a reminder that the character of Twitter (rebranded by Musk as ‘X’) feels fundamentally different. In the wake of the many and often-discussed changes to the site since his purchase of it in 2022, from reinstating previously-banned figures to Musk’s own use of the site to spread disinformation, it’s unsurprising that many of the key figures in the #MedievalTwitter community have upped sticks and moved on. This is something that Alicia’s book grapples admirably with, devoting an entire chapter to ‘Musk’s medievalism’. Importantly, Spencer-Hall doesn’t fall into the trap (as I might have done) of eulogising Twitter ‘as it was’, and highlights the numerous problems that it has always faced with trolling and abuse (particularly for medievalists of colour). Nevertheless, Alicia does make a compelling case that the ‘premature demise’ of Twitter has caused us to lose something: namely, the community ethos that dominated prior to its takeover, and the vibrant medievalist community that thrived, in spite of the platform’s issues. As the free sticker that I received with my copy of the book put it, Twitter ‘was a cesspit, but it was our cesspit’.

I can’t possibly do justice to Alicia’s book in one blog post, particularly since it ranges far beyond simply analysing a single social media platform. Twitter-adjacent readings of medieval texts, from Marie de France’s Lais to the Book of Margery Kempe, form an important part of the volume, and I’d encourage you to get hold of a copy (either from the publisher or via your local library). The final chapter of the book, though, left me asking one simple question, à la King George III from Hamilton: what comes next?

Plenty of colleagues are, of course, still present on X, and the decision on whether or not to remain active on the platform is of course an individual one. In the meantime, though, the battle to take on the mantle of Twitter has become a three-way fight between BlueSky, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Of these three, BlueSky is by far the closest (in both form and function) to Twitter, as befits its origin as an internal Twitter project. If you’re looking for somewhere new with a similar feel to Twitter, BlueSky — with its comfortingly familiar short-form posts, timeline, and array of ‘reply’ / ‘repost’ / ‘like’ buttons between each posts — is probably the place for you.

At present, the main drawback with BlueSky — as with any new social media platform — is its lack of reach: in spite of the many articles trumpeting its user-base, #MedievalSky (the hashtag coined in imitation of #MedievalTwitter) remains something of a wasteland. I can only hope that this will change with time.

The other two sites vying to replace Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn, don’t have this problem, with large user-bases and several years of built-up steam already in their proverbial tanks. On a purely personal level, having no real experience of the short-form video world of TikTok, I’ve found that LinkedIn has been steadily becoming the place to go for work-related social media.

Of course, this hasn’t come without a cost. The phrase ‘[I’m] delighted to announce …’ has long been something of a meme on Twitter, as resistance started to grow in the face of a perceived culture of self-promotion. LinkedIn, ironically, seems almost to be self-promotion incarnate: scrolling through the latest posts in my feed, it’s announcements that dominate, whether they’re of forthcoming publications, new opportunities, or reports back from official visits. By contrast, vignettes from archives trips, terrible puns, and questions for colleagues — the things that I joined Twitter for all those years ago — are conspicuous by their absence, as is (whisper it) a sense of a dedicated medievalist community. This isn’t all LinkedIn’s fault, of course: the social media landscape has metamorphosed dramatically over the past few years. Recognition, not conversation, is the name of the game nowadays, as Inger Mewburn puts it very well:

‘Promote your work’ on social media is now an endless game of cut and paste with no time left over to talk to people.

Inger Mewburn, ‘The Enshittification of Academic Social Media’ (July 2023)

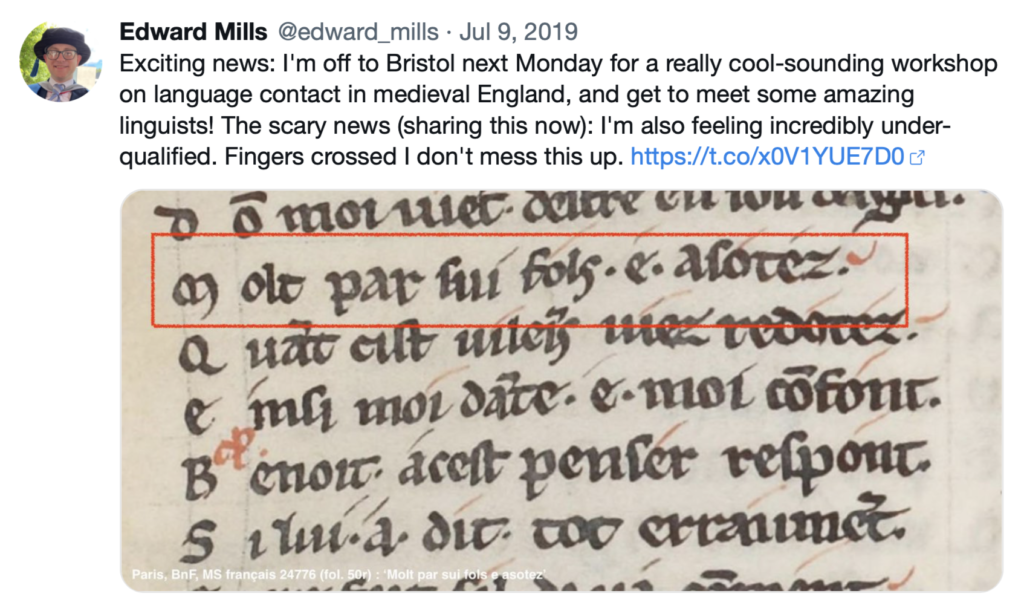

Six years ago, when feeling out-of-my-depth ahead of a conference, I shared this message on Twitter:

Beneath the veneer of ‘here’s-a-cool-thing’ that I’m putting out, you’ll have spotted that there’s a nervousness present in this post, and an acknowledgement that I wasn’t feeling as confident as I might have seemed. I wouldn’t post that on LinkedIn now: for all the talk of being your ‘whole self’, it would still be unmistakably Unusual to post something like that on a platform that feels (for want of a better phrase) much more corporate. To be brutally honest … I miss that. Kelly Louise Preece spent a year in 2019 documenting acts of self-care exclusively through Twitter, and for want of a better phrase, it’s hard to imagine something so personal and heartfelt appearing on LinkedIn today. [*]

What will the medievalist social media landscape look like in another five years’ time? I certainly don’t know. Perhaps one of the platforms mentioned above will take on the mantle of Twitter, becoming the site against which all other medieval-friendly social media platforms are measured; perhaps not. In any case, consider this an invitation, if you’re following us on Instagram, to interact with us rather than simply following us: tell us what you’re up to, share your news, and ask questions.

I will, though, nail my colours to the mast in one respect. Since blogs don’t appear to be going anywhere, stay tuned for the next ‘social media for medievalists’ post on this platform … coming to you at some point in mid-2030.

[*] Edit (post-publication): thanks to Kelly Louise Preece for pointing out that there is at least one example of precisely this ‘sharing self-care’ practice on LinkedIn and Instagram, as advocated by Narelle Lemon and her ‘Citizen Wellbeing Scientist‘ project. Hopefully this work can set an example for medievalists to follow.

Featured image: a bird, from Tours, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 558 (fol. 191v). Any resemblances to former social media logos are entirely uncoincidental.