Posted by Katie Brown

3 November 2025We’re welcoming (whisper it) a modernist to the blog this week, as Katie Brown, Associate Professor in Latin American Cultural Studies, shares exciting news about a new digital edition and translation project that’s brought her back across centuries (and continents) to 13th-century Spain.

How do you grapple with a more than 6000-page text that draws on Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources to tell the entirety of human history? For Professor Francisco Peña of University of British Columbia Okanagan, the answer is clear: assemble an international, interdisciplinary team.

Prof Peña first encountered the General estoria – a 13th century universal history commissioned by Alfonso X ‘El Sabio’, or ‘the Wise’ – when researching how the story of how Cain and Abel has been retold across Spanish texts. He describes his reaction as like the moment in Jaws when they first encounter the shark: “You’re gonna need a bigger boat!” For the last ten years, and thanks to several grants from the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, he has gathered experts across Spanish philology, religious studies, medieval history, Arabic studies and digital humanities, all working together to edit, annotate, translate and share the General estoria, culminating in the recent award of a CA$2.1 million SSHRC Partnership Grant to fund the project until 2032.

As a Latin Americanist whose day-to-day research is firmly set in the 21st century, medieval Iberia is quite a departure for me, but an adventure I am relishing. I came to the project in 2019 when Prof Peña visited Exeter, building on the close relationship between our respective institutions, and I pitched the idea of training Exeter language students to collaboratively translate the first book of the General estoria for the digital edition. Thanks to UBCO-Exeter catalyst funding, we ran three successful trials of student internships in preparation for the SSHRC bid. As a result, I became a Co-Director of the project, responsible for training and mentoring.

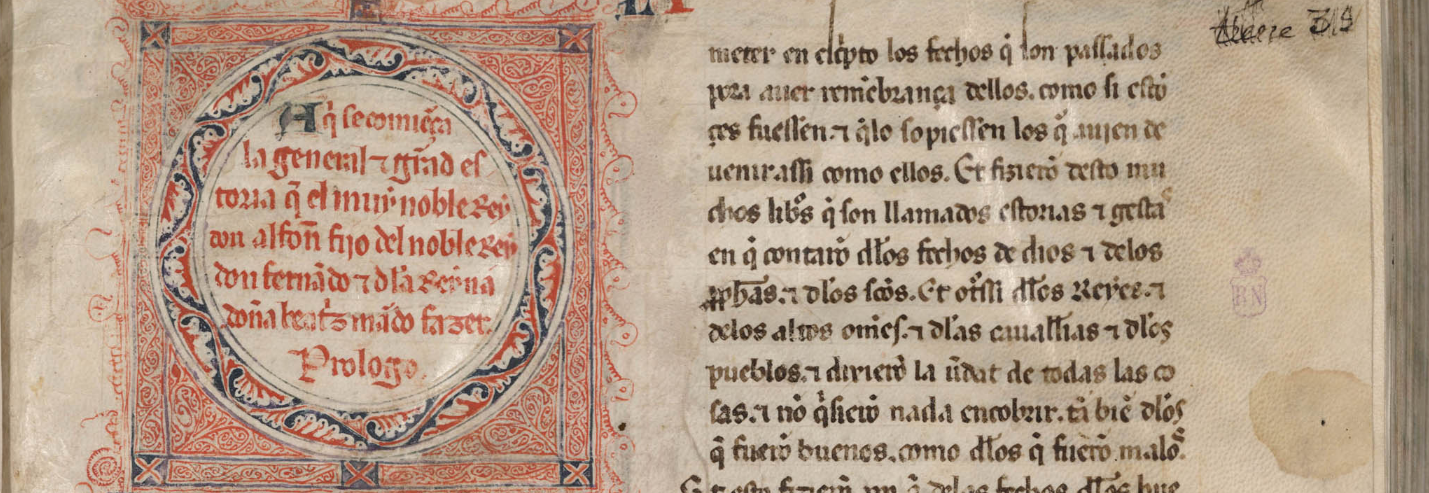

Each year I take up to four students – a mixture of MA Translation and BA Modern Languages – to the idyllic San Millán de la Cogolla, in La Rioja, where we spend a week at Cilengua, a research institute dedicated to the Spanish language. Here experts in the history of Spanish – Dr Fernando García Andreva and Dr Miguel de las Heras Calvo – give the students a crash course in the language of Alfonso’s time. Thankfully 13th century Spanish is much closer to its modern version than 13th century English is to today’s language! Nonetheless, the text was one of the first large-scale attempts to use the vernacular to convey knowledge instead of Latin, and a fascinating document of the development of Castilian language.

To shape this language of science and offer the broadest possible knowledge to his people, Alfonso employed a ‘scriptorium’ of Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars to translate texts from Arabic and Hebrew. 800 years later, we have our own scriptorium, as students work collaboratively to translate the text to English, sharing ideas, research and potential translations, editing each other’s suggestions and working closely with the international team of researchers to address questions about what the text means. On several occasions, our translation questions have led to new insights into the text.

Translating the General estoria has led us down many rabbit holes. For a start, I never imagined spending quite so much time on BibleGateway, comparing multiple translations of the Bible. Every account contains interjections, sharing knowledge and theories from across the world and across time. Just this week, in translating a section about where the descendants of Noah settled, we learned about the etymology of Persia; that the authors believed Zeus did not turn into a bull to steal Europa but sailed on a ship with a bull painted on the side; and that some thought Ethiopia and Egypt should form a separate, fourth continent, alongside Europe, Asia and Africa. One of our favourite things about the text is how it often gives several competing explanations for a topic and encourages the reader (or listener) to make up their own mind about which they prefer.

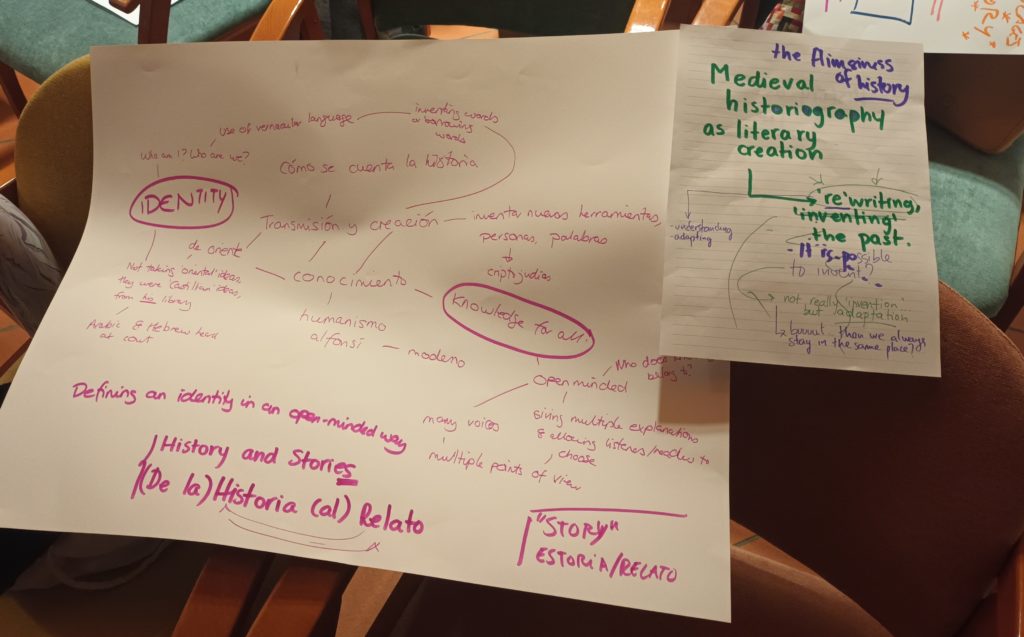

The spirit of intellectual curiosity that imbues the General estoria drives our project team. I’ve just returned from three days in Granada where around 30 of us gathered to share our approaches to the General estoria, from mapping the connections with other medieval universal histories to tracing the influence of the women in Alfonso’s life. I’m now more excited than ever to see what secrets are in store for us next and to share them via our digital edition.

Header image: Madrid, Biblioteca nacional de España, MSS/816 (fol. 1r)