Posted by James Gordon Clark

1 December 2025As his edited Cambridge Companion to Matthew Paris nears publication, James Clark takes a look at the life and afterlife of the famous medieval polymath.

Matthew Paris is one of the few authors of medieval England whose name has always been known. It’s a select group: Bede of Monkwearmouth, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Geoffrey Chaucer … could that be it? It’s easy to forget that so many of the names that seem ubiquitous in Medieval Studies have arrived on the scene only recently. Perhaps most famously, Margery Kempe only emerged out of the shadows in and after 1934, when the pioneer of feminist scholarship Hope Emily Allen was able to consult the sole manuscript of her book in a private family library. The Gawain poet (OK, not quite an author with a verifiable name) was hidden in plain sight – among with the remains of Sir Robert Cotton’s library – until 1824. Another of Cotton’s treasures was a manuscript of the life of Ælfred of Wessex (r. 871-99) attributed to Asser, monk and Bishop of Sherborne. Today, he can claim the ultimate accolade of a handy translation in the Penguin Classics series (in good company with Margery and our Gawain ghost-writer), but the manuscript itself was lost in the fire that ripped through the Cotton Library at Ashburnham House in 1731. Again, it’s only in the modern era of Medieval Studies that he has become a household name.

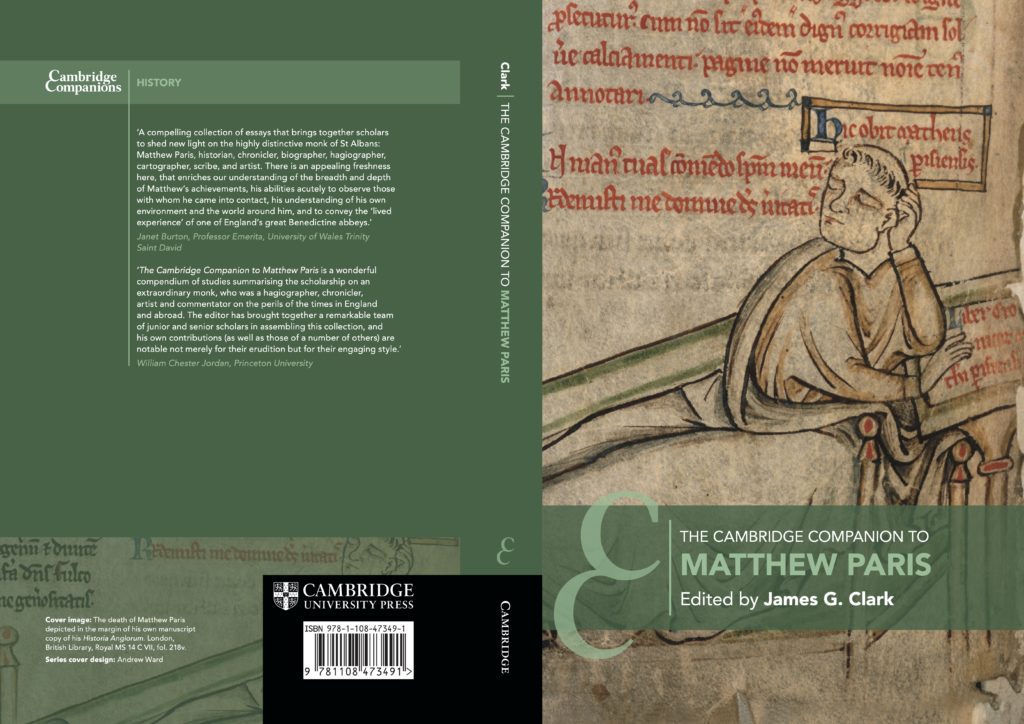

It was quite different for Matthew Paris. His death, probably in 1259, was marked by the monks of his own, Benedictine community of St Albans. An obituary notice was added to the margin of a manuscript containing his chronicle which he himself had begun, a rare accolade for one who was not an abbot; and one of them also painted a poignant miniature of the great man on his death bed. A century on and he was remembered by his successors at St Albans when they put together a great Book of Benefactors which in fact commemorated not only their glittering roll call of royal and episcopal patrons but also their abbots and a handful of their most remarkable monks. By the turn of the fifteenth century, the books of chronicles for which Matthew is best known were being sought out by scholars and writers from outside of the monastery’s immediate network. St Albans stoked the renown of his books. In 1458, when King Henry VI visited the abbey on route for a Great Council at Westminster he was shown Matthew’s beautifully illustrated book of the lives and martyrdom of the patron saints, Alban and Amphibalus. When the abbey succumbed to the Tudor dissolutions in 1539 and the book collection was broken up, Matthew’s chronicles were swiftly scooped up by the kingdom’s leading book hunters, John Bale, John Dee and Matthew Parker. Bale built Matthew’s reputation in print, declaring his early history of the Reformation, The Actes of the Votaryes, ‘if you want to know the truth, read Matthew Paris’. Ironically for a career monk, post-Reformation England made Matthew something of a champion, warming to his shrewd and cynical eye on the struggles of Henry III with the papacy.

Editing the new Cambridge Companion to Matthew Paris, I’ve been struck by how his afterlife has left us as rich a body of source material as his career itself. The reading of Matthew Paris and responses to his remarkable artwork over seven and a half centuries track our shifting and changing attitudes to medieval culture.

But synthesising past and present research on his output and its legacy has also highlighted that there remains one aspect of his profile left languishing in the shadows. Who was he? Other than his obituary, the only source of his life is what Matthew wrote himself. He tells us when he arrived at St Albans to make his monastic profession (1217) and he relates how he formed personal relationships with Henry III, his brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and a network of courtiers and government officials, joining the royal party at Westminster and Clarendon Palace. Yet he reveals nothing of his background. The Commonwealth historian, Thomas Fuller, in his book of the Worthies of England claimed Matthew for Cambridgeshire, noting that the name was known in that county. In fact, Paris can be found across the south of England, from London, westward.

When writing my introduction to the Companion, I was reminded of a passing reference in one of the miracle stories with which Matthew padded out his book of the lives of Alban and Amphibalus. It concerned a pilgrim who came to St Albans after having been disappointed in their supplications at a holy well in Cornwall. The text copied in the manuscript calls this the well of ‘Saint Cradoc’ which is likely to mean Saint Cadoc, which was found in the parish of Padstow on the county’s northern coast (I’m grateful to Nicholas Orme for confirming my hunch here). It is a surprisingly precise reference to a regional location which stands apart from the other miracles stories which are all oriented to the south-east region close to St Albans. There is one further Cornwall reference in a St Albans miracle story, among a sequence which also may have been compiled by Matthew. This concerns a secular priest, named Sylvester of Cornwall, who was said to have journeyed from the West Country after being disappointed at the unresponsive shrines of the Benedictine abbey at Glastonbury.

These are glancing notices of Cornwall, of course, but I’ve also found that in Matthew’s great Chronica maiora he shows strikingly good knowledge of the local economy and topography. In his entry for the year 1241 he reported the discovery of tin deposits in Germany and reflected that it threatened English tinners who operated uniquely in Cornwall; he also noted the piracy of William de Marisco offshore from Lundy Island which is ‘not far from Bristol, Devon and Cornwall’; then for 1242 he told of Earl Richard’s shipwreck on the Scillies. This he might have had from his friend the earl’s mouth, of course, but perhaps not the precise detail he added, that the islands stood at the same distance from the Cornish mainland as the Isle of Wight is from Dover. We know the West Country has a great reputation for Medieval Studies; is it possible we can add to it the famous name of Matthew Paris?

The Cambridge Companion to Matthew Paris will be available imminently from all good bookshops, and online via the Cambridge University Press website. Featured image: the death of Matthew Paris, from London, British Library, Royal MS 14 C VII, fol. 218v.