Posted by Lucas McMahon

16 February 2026Lucas McMahon is a British Academy International Postdoctoral Fellow at Exeter, where his work in the Centre focuses on the late Roman and Byzantine world. In the wake of a recent open-access publication, ‘Signaling Empire Between the Abbasid-Byzantine Frontier and Constantinople’, Lucas has penned two posts for the blog that bring together geography, the digital humanities, and J. R. R. Tolkien.

Nearly all of us have a common point of reference when it comes to fire beacons: Peter Jackson’s 2003 adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King. In the film, Gandalf gets his Hobbit companion Pippin to light the beacon fire above Minas Tirith, thus informing the Kingdom of Rohan that help is required. We are then treated to New Zealand’s impressive mountain scenery as the beacons are lit in sequence. The message is received in Rohan and King Theoden prepares to march off for war.

Tolkien did not invent optical signalling. Fire and smoke signals were used widely around the world, and also in the Middle Ages. A system is believed to have run between Chichester and London at some point in the second half of the first millennium, for example. However, such systems have a number of inherent limitations, which the Return of the King illuminates well. First, the signal can bring only one bit of information: when off, Gondor is fine; when on, Gondor requires help. Second, optical communication systems are usually only one way: Theoden responds that Rohan will answer Gondor’s call, but using the language of real-time communication. Third, the initial beacon fire was not intended to be lit. The message went out, but against the will of authorities; once the message was sent it cannot be undone, nor can additional information be added at anything like the same speed.

Humans have been aware of these problems for a long time. At least from the second-century BC the Greek historian Polybios had proposed a number of alternatives to fire beacons which could send more information (albeit at the cost of increased complexity). There’s little evidence anyone took up Polybios’ advancements, though, and Roman history is replete with optical signalling without any serious complexity. Theories of massive beacon towers near York or complex signalling procedures based on possible sightlines along Hadrian’s Wall and on the Germanic frontier have been proposed, but there is no evidence that anything beyond simple, binary signalling with pre-arranged messages was used regularly.

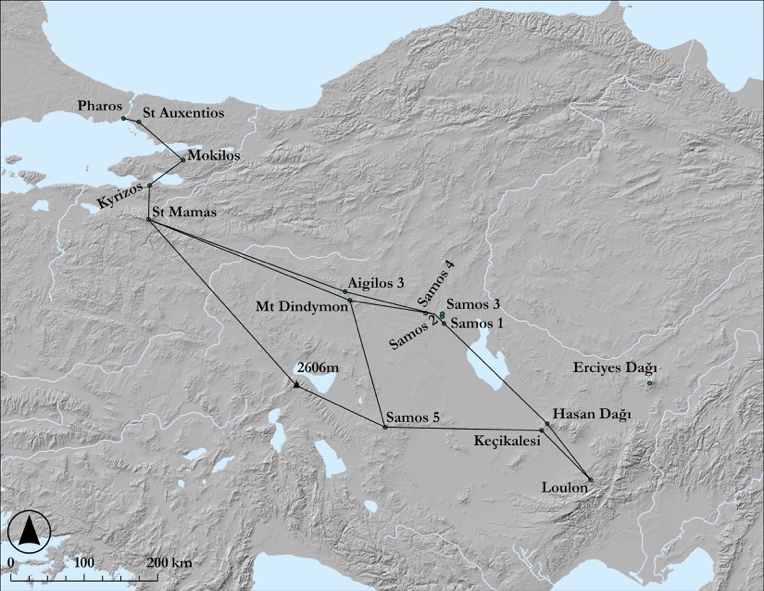

The one exception to all of this is the famous Roman (“Byzantine”) beacon chain from the ninth century. We know about it from a number of texts from the tenth century, and they make a number of claims about this beacon chain: that it was very long, running all the way from the Tauros Mountains to Constantinople; that this was accomplished with only nine stations; and that the chain could send several different messages to Constantinople within an hour. These descriptions are in narrative historical texts, set in relation to stories about how the Abbasid caliph was trying to get the system’s designer, a certain Leon the Mathematician (more properly, “the Philosopher”) to come to Baghdad. Another story is about how the emperor Michael III (842-67), who the texts have a particularly negative opinion of, shut the beacon chain down to the detriment of the empire.

Several questions come out of this. Can such a small number of beacons cross some 700 km of rough Anatolian terrain? How did it actually work? And what are the stories about its designer and it being mothballed trying to communicate? In a recent article, I have proposed some answers to these questions. Next week, I’ll talk about what I found when I returned to the specific political context of the beacon chain’s foundation, but today, I’ll show what the digital humanities have to offer, through historical Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis.

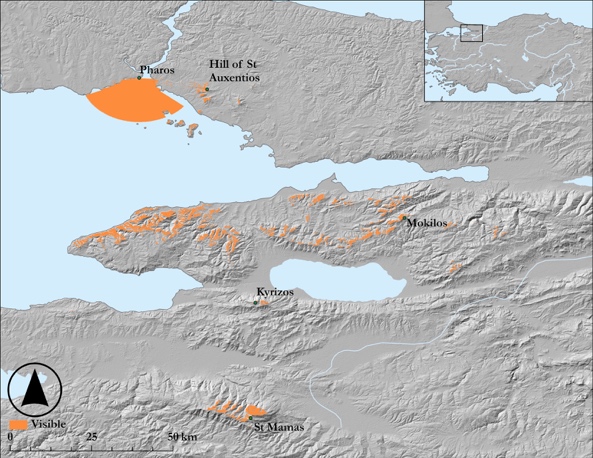

In the GIS analysis, I used a simple technique: the viewshed, in which the user defines a point in a digital landscape and the algorithm returns a result of what can and cannot be seen from that spot. It looks like this:

The texts give us names of the beacon sites, but other than the first and the last stations, none have been identified. Past scholarship has given us a bunch of potential sites, though, so I set out to do some digital experimental archaeology, following up older hypotheses, and when none of those actually worked, trying to find alternative potential sites in the landscape. The problem is that there were not enough beacon stations in the central and eastern parts of the chain to make it work easily, and the low, rolling hills of the central Anatolian plateau means that few places had especially long views. The distances involved here are vast, with some links in the chain pushing upwards of 100 km. This is a lot more than we get in other historical signalling cases: the aforementioned Chichester-London line has at least six stations for a mere 90 km, and most chains elsewhere average 20-30 km between stations. Ultimately, I found a handful of possible solutions, thus answering the question that the stated number of beacons could in theory stretch from the Tauros Mountains to Constantinople.

Some of those distances are vast, though, which raises further issues. It’s likely that the chain could only have worked at night. The fires would have needed to have been huge, which probably means that activating the chain a second time shortly after the first use would be difficult. Fuel consumption would be high. Moreover, one of the texts tells us a few of the different messages that the chain could send: a raid, war, fire, or something else. These are not detailed messages (especially “something else”). So what we have here looks like an expensive, complex, precarious system, that at best might provide some vague information at the very real cost of sending wrong or erroneous information. So maybe it could work, but why build it and maintain it, even for a short period?

Lucas McMahon returns to the blog next week. Featured image: the beacon at Minas Tirith is lit, in Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003).