Posted by James Gordon Clark

8 April 2017In just a few years, family history research has become something of a cultural phenomenon. Proof of this will be apparent to any professional researcher arriving at the National Archives or – perhaps more especially – at a regional record office or heritage centre. Now they will find themselves explaining to the staff that unlike their typical visitor they have in fact called up this charter or that diocesan register for its own intrinsic interest and not simply because of some passing reference to a presumed ancestor. Of course, this surge of interest in family research might fairly be said to have been the salvation of county and city archives, which have seemed ever more vulnerable in face of local authority austerity. In fact the courage of some to cut loose from the direct control of councils owes much to the foot-fall they have seen from self-taught researchers of all ages with a passion discover more about their own past.

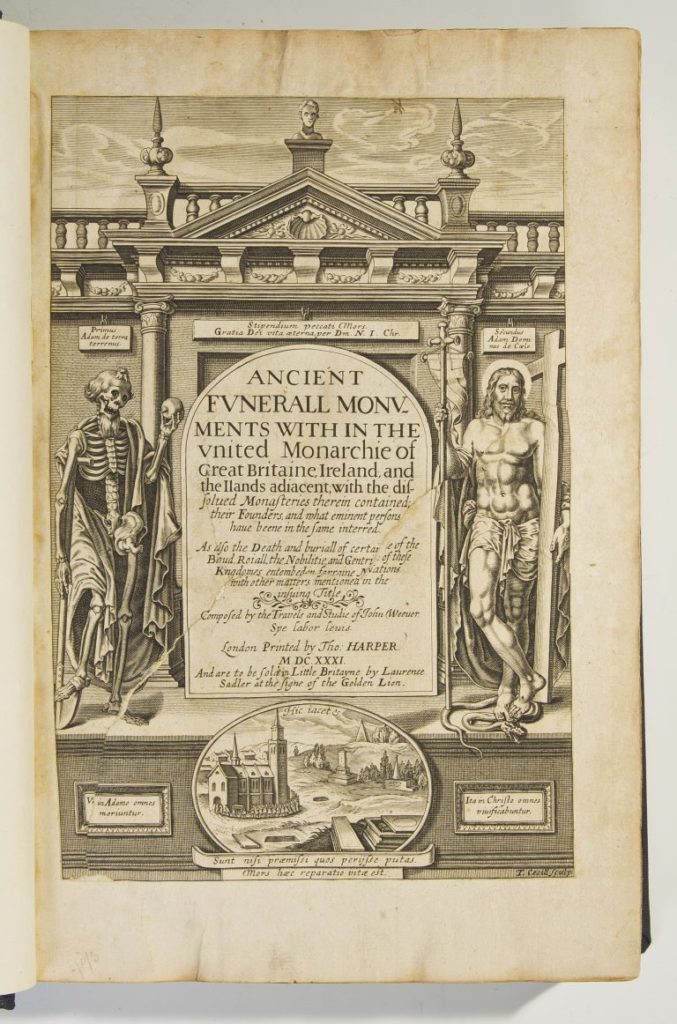

The fashion for family history and its place in prime-time TV may be a recent development but, of course, the tracing of family lines does have a long… pedigree. In England its origins as a subject of scholarly enquiry are usually traced to the years between the Break with Rome (1534) and the outbreak of the Civil War (1642). The early anxieties and later ambitions of the Tudor monarchy gave rise to statutory measures for the regulation of social status and the use of a growing governmental bureaucracy to subject the political nation and the authority they exerted in their own provinces to ever closer, central scrutiny. Henry VIII initiated a cycle of heraldic visitations which continued at regular intervals – with the exception of the years of civil war – until the Glorious Revolution. The crown’s heralds held local elites to account for the arms, and, of course, the titles to which they were accustomed to lay claim. The coming of the visitors caused families to recover their records, create a synthesis and in many instances, to commit them to parchment in a genealogical roll. They were helped in their response by new forms of national and regional history: William Camden’s Britannia (1586) brought the histories of the nation’s counties into focus for the first time; John Weever’s Ancient funeral monuments (1631) gave its readers a glimpse of a distant ancestry which might be their own; in Monasticon Anglicanum (1655-73) William Dugdale and Roger Dodsworth pieced together the testimony of old monastic cartularies and chronicles still widely scattered in the libraries of provincial gentlemen.

Before the relationship between crown and political nation was challenged, and changed, in these years, it is generally assumed that ideas of family identity were not so well focused and that noble and gentry society did not demonstrate the same enterprise in the recording of its own history. The adoption and use of (coats of) arms remained fluid until the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The proof of the right to particular arms or indeed to an inheritance as a whole might be mustered ad hoc but was not a routine feature of noble or gentry discourse. Genealogy as a concept was well understood but was pursued for the most part only in clerical contexts where the descent of emperors, kings, and pontiffs provided a chronological framework for a chronicle narrative, and a narrative of the founder of the monastery and their family line offered a degree of institutional security to a convent community. It has often been suggested that the very first sign of these impulses passing over into lay circles was the making of the Rous Roll, the genealogical history compiled by John Rous, perhaps for Anne Neville before the Battle of Bosworth (1485).

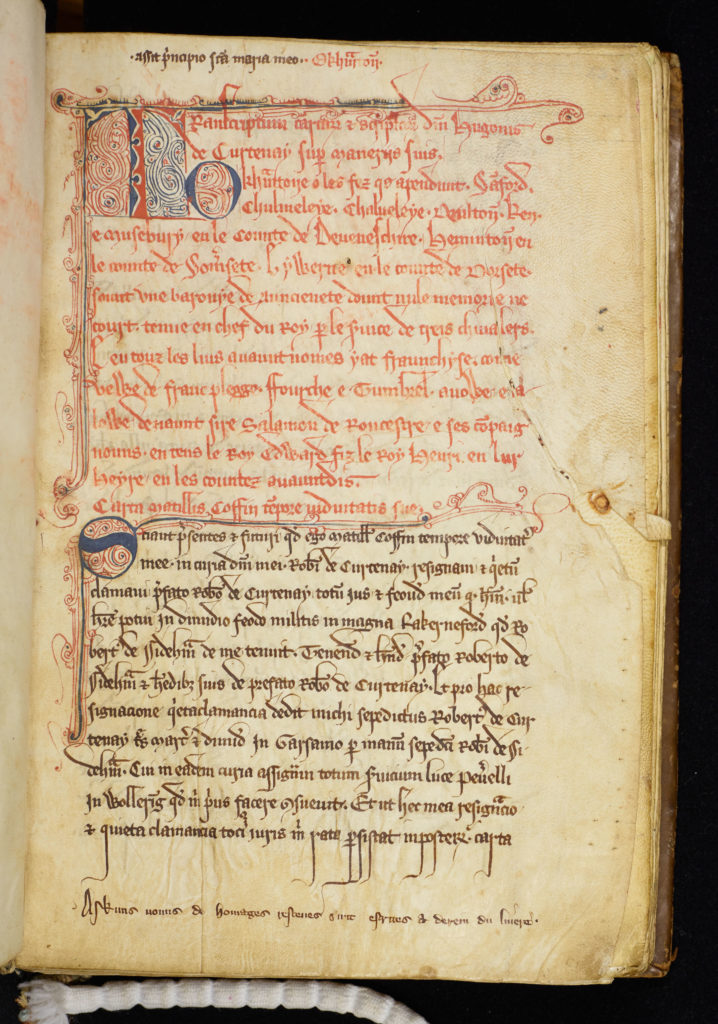

Yet a manuscript from the Courtenay archives at Powderham Castle, near Exeter, now digitised by specialists from Exeter University’s Digital Humanities team, Charlotte Tupman and Graham Fereday, may present something of a challenge to this conventional view. The Courtenay cartulary has only recently been returned to Powderham and has not been available to researchers for nearly forty years.

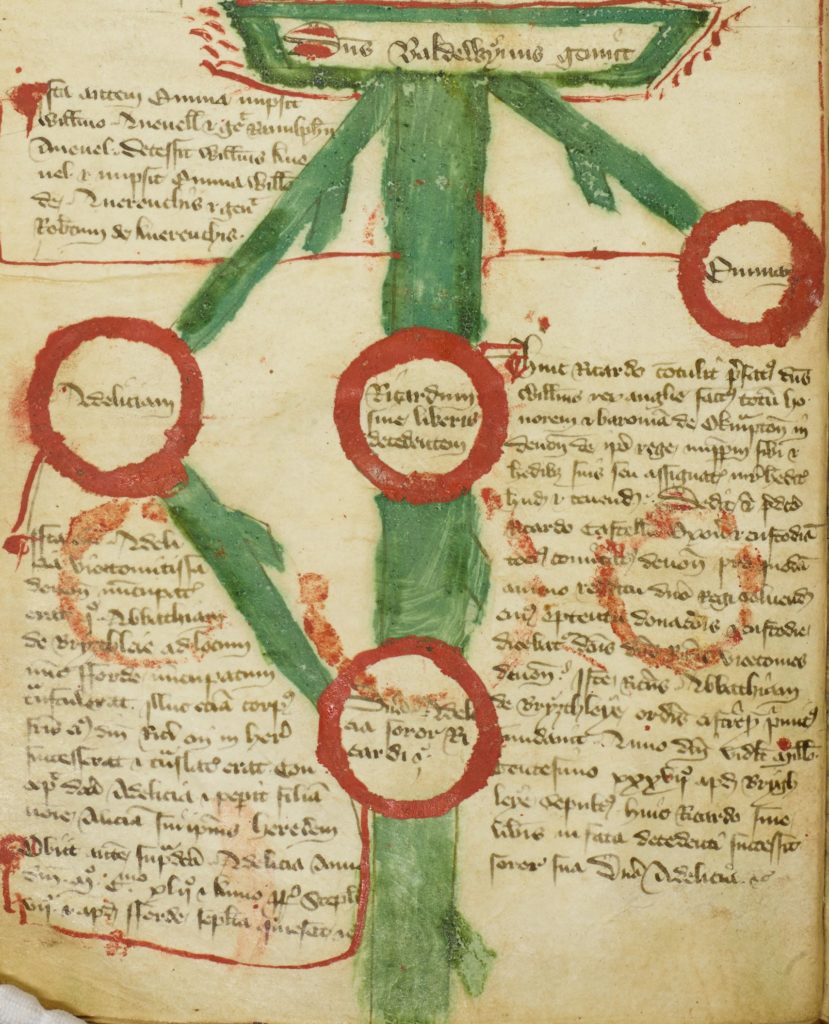

It was first brought together in the third quarter of the fourteenth century and its principal contents track the Courtenay family’s acquisition of the old Norman barony of Okehampton which became the mainstay of their medieval earldom, and their commercial development of new towns at the east – Colyford – and the west – Kennford – of their domain. Perhaps as much as fifty years after the manuscript was begun, c. 1400-1425, quires were added at the front containing a family tree and family chronicle. Unusually at this date, the structure of the tree is formed not only of lines and roundels but also with the stem and branches of a tree, formed with broad strokes of a bright green paint. It begins not with the Courtenay family themselves but with the forebears they claimed, with the earldom, the Norman families of De Brionne and De Redvers who held respectively the shrievalty and nascent earldom of Devon in the first generations after the Conquest.

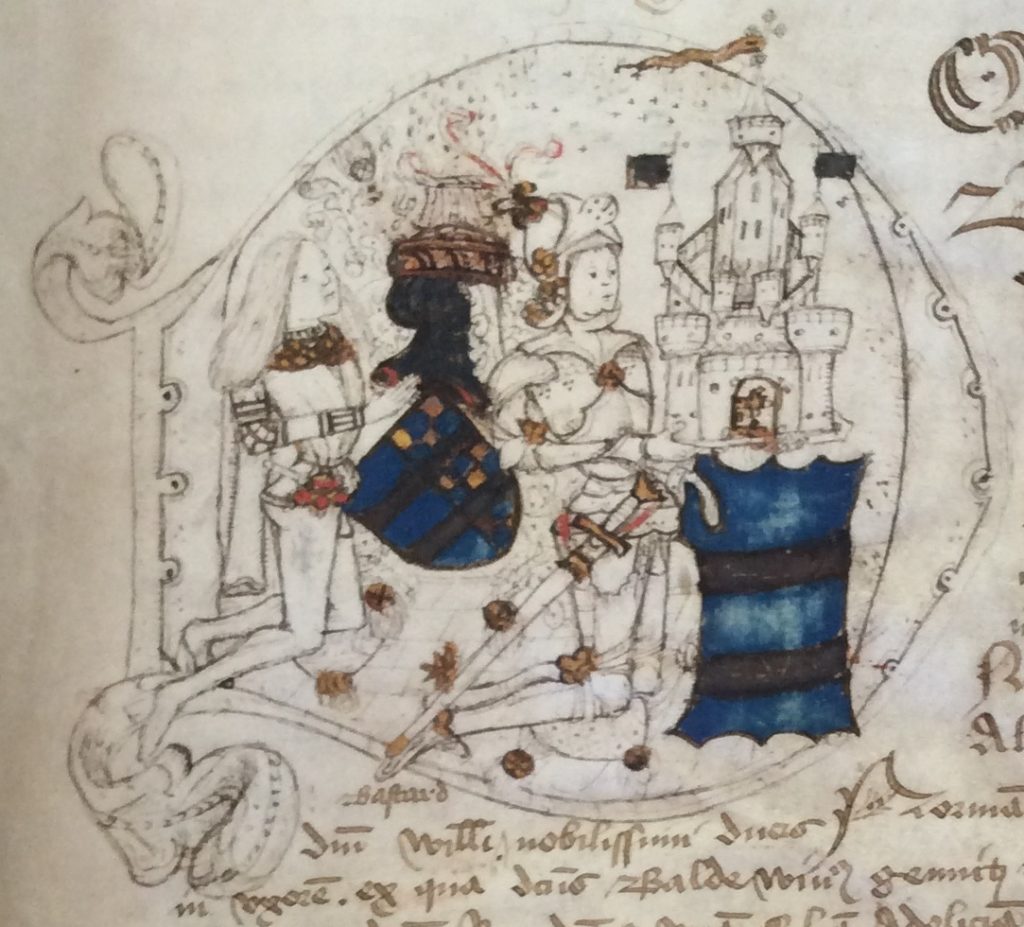

The tree follows the Courtenays from their arrival in England from their original French home at Chateau-Renard in the Val de Loire, their intermarriage with these Norman baronial lines and their claim of the earldom finally recognised by Edward III in 1340. It continues with the succession of Earl Hugh III de Courtenay (d. 1377) who married Margaret de Bohun (d. 1391), granddaughter of Edward I, whose marriage portion included Powderham. Their fourth son, Sir Philip Courtenay (d. 1406), built the castle and it is his descendants who recovered the earldom. The family chronicle expands this narrative and is illustrated with the blazons associated with each generation of the Courtenays and their forbears.

The research of these fifteenth-century Courtenays was based largely on the foundation history of the Cistercian Abbey of Forde, of which they were patrons. The text that is woven around the tree, and continues on into the cartulary not only records the names of each generation, their marriages, issue, obituaries and their place of burial; it also includes passages from the (now lost) longer narrative of the fortunes of the Forde colony of monks from their first settlement at Brightley near Okehampton in 1133 down to the beginning of the fourteenth century. While a number of Cistercian houses compiled genealogies of their founders, it is rare to be able to demonstrate their direct transmission into the records and books of a lay household. Without the monastic original how far the Courtenays copied a Cistercian manuscript is unclear but it seems likely that the visualisation of their tree and the arms in their lineage – each finely painted and picked out in gold leaf – represent their own creative input. In doing so, the corporate, institutional identity which charged the Cistercian narrative was overlaid with its precise counterpoint, an expression of dynastic lordship. Interestingly, the territorial outlook of the original, which represented the White Monks reaching out across the West Country, was retained more-or-less verbatim no doubt because its tone of seigniorial ambition was well-suited to the Courtenays’ own purpose.

Remarkably, there is a second manuscript in the Powderham archives which bears witness to the appropriation of Cistercian narrative for the purposes of lay family history. A parchment booklet written in the first half of the sixteenth century contains another copy of the foundation narrative and later history of Forde.

The booklet carries a dated ownership inscription naming William Strode (d. 1579), a major landowner in Somerset and Devon who was energetic in buying up estates at the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Perhaps the pinnacle of Strode’s rise to regional power was his marriage into the Courtenay dynasty. It was his entry into the hold monastic heartland and into the region’s noble lineage which persuaded him to assimilate the same dynastic narrative – already re-purposed once, in the fifteenth century – as his own. More than a decade after the Cistercian community had itself been driven from Forde, their pioneering work in genealogy provided a template for fashioning the identity of an up-and-coming family.

The Courtenay family tree, the cartulary and William Strode’s book form part of an exhibition now open to visitors to Powderham Castle curated by Exeter’s Digital Humanities team together with James Clark and Henry French from Exeter’s Department of History.