Posted by Levi Roach

16 June 2017What happens after empire? In an age in which Europe continues to grapple with its colonial past, there could scarcely be a more timely question. Yet while the Fall of Rome is frequently invoked within political debates (for better or for worse), the same can scarcely be said of the Carolingian Empire, which spanned much of northern and western Europe in the eighth and ninth centuries, fundamentally transforming the continent’s political landscape.

The decision of the HERA partnership to fund a major project investigating the aftermath of the Carolingian Empire – the ‘transformation of the Carolingian world’, to use the favoured terminology – is therefore to be warmly welcomed. Sarah Hamilton has already written about the project’s aims and her contribution, so I would like to take the opportunity to reflect more generally on the post-Carolingian period, in the light of the project’s inaugural conference in Berlin last month.

As Stefan Esders, our host, explained in his introductory remarks, the core idea behind the project is to view the tenth century not simply as a prelude to the central Middle Ages, but as a development out of the Carolingian age. The focus is therefore on change as well as continuity, on seeing how similar texts and ideas came to take on new meanings in the post-Carolingian world. These themes came through strongly in almost all of the papers (helpful summaries of which can be found by searching #UNUP on Twitter). A common refrain was that texts and ideas developed in the Carolingian period continued to be used and applied within the tenth century, whether in the form of local institutional histories (Koziol), notions of identity (Diesenberger), legal materials (Esders), liturgical laudes (Welton) or normative ordinances (West). Yet such apparent continuity can be misleading, as these (and other) speakers noted: even when copying or imitating Carolingian texts or genres, tenth-century writers repackaged these for the present; this was not a case of stagnation or idle nostalgia, but of strikingly new variations on existing themes. Then as now, invoking the past was a powerful rhetorical tool, but not one which should be mistaken for straightforward continuity.

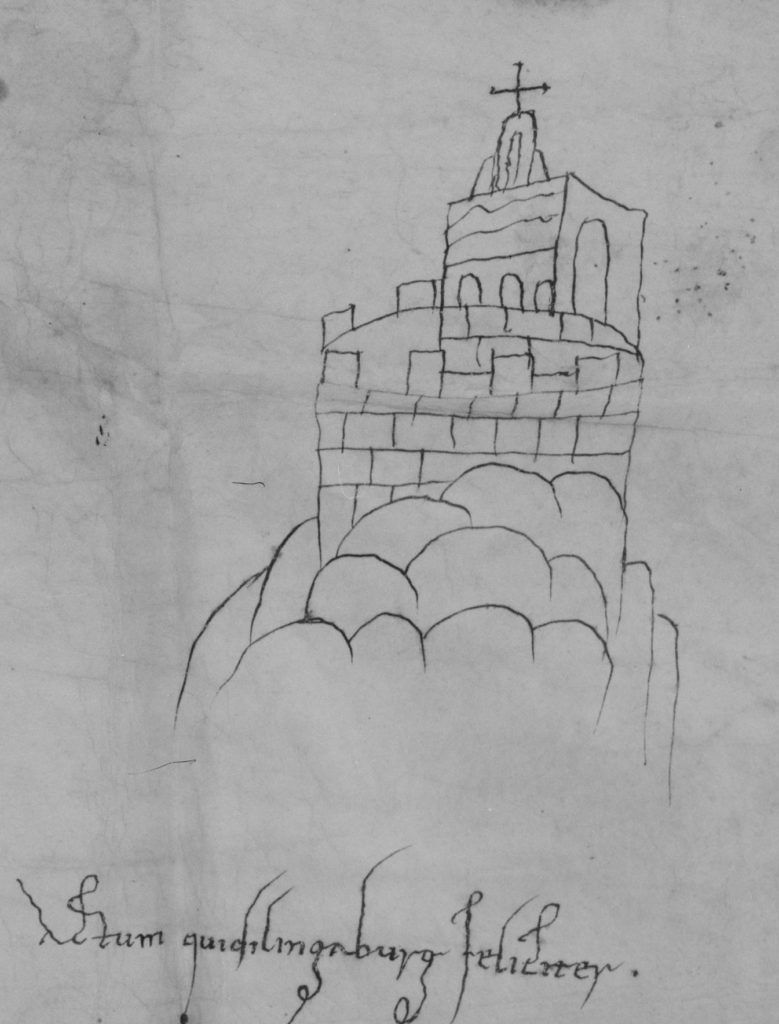

Nor it was not all about continuity either. The focus of Sarah Hamilton’s paper was rites of excommunication, which are first recorded in the tenth century. This raises important questions about the impetus behind such acts of codification. Similarly my own paper touched on some of the earliest examples of imitative script – that is, self-consciously archaic writing – from Europe, whilst Sarah Greer provided a thoughtful consideration of the foundation of Quedlinburg, one of the most important new convents of the tenth century. There was, therefore, plenty new going on in these years. But just as change can often be detected within continuity, so one must be careful not to exaggerate the novelty of these developments: new texts, rites and convents certainly came to the fore, but these often owed much to the past.

The cardinal lesson of the conference – if it might be distilled into one – was therefore that we must be wary of overstated claims about both continuity and change: the same texts and artefacts can mean very different things within different contexts, while different texts and artefacts may fulfil very similar functions. Perhaps most importantly, the papers all underscored the vitality of the ‘long tenth century’ as a period of transition between the early and central Middle Ages. It has long been my belief that historians of the period could learn a great deal from scholars of Late Antiquity – who have transcended the ancient/medieval divide so well – and it is promising to see steps in this direction. Indeed, as Patrick Geary noted in the concluding discussion, it would be nice to see more experts on the eleventh and twelfth century integrated as the project continues. It is only when we start to shed our identities as ‘early’ and ‘central’ medievalists that we will truly start to understand these fascinating and dynamic years.

Whether there are any lessons to be learned here for a nation facing the prospect of Brexit and dreaming of ‘Empire 2.0’, is perhaps a question best left to a different day. For the time being, it looks as if the future of tenth-century studies is bright; this ‘Age of Iron’ (as Cardinal Baronio once called it) may yet come to be appreciated in its full diversity and complexity.