Posted by Levi Roach

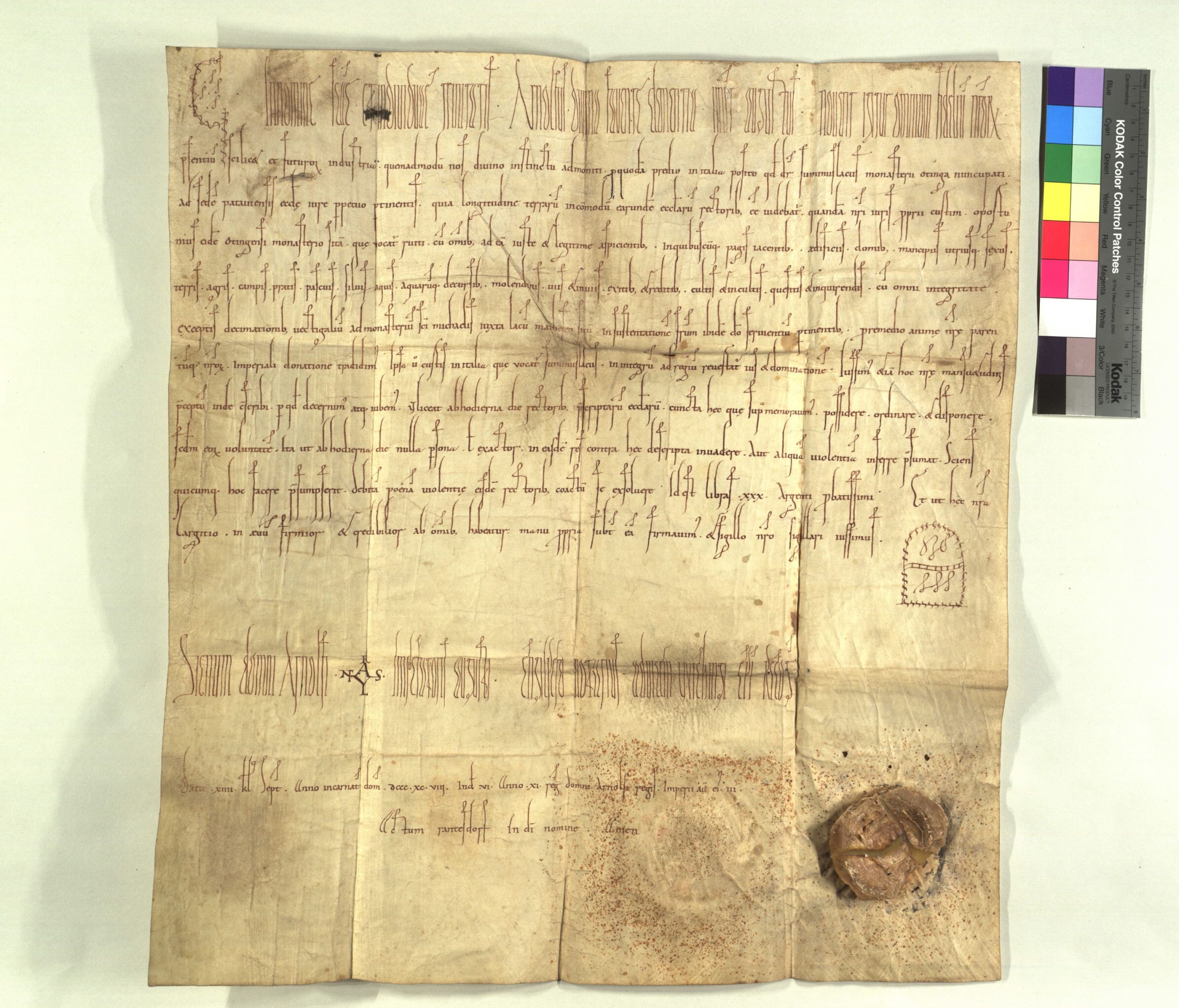

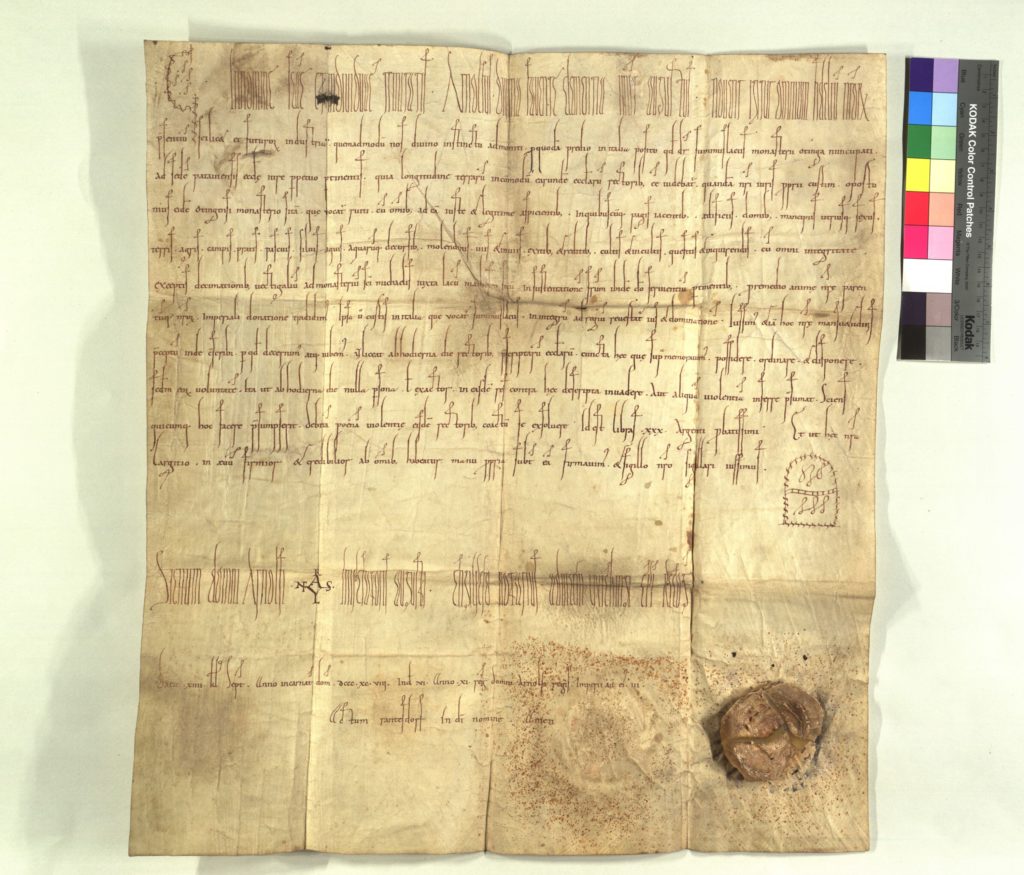

31 July 2017It brings me great pleasure to announce that the Arts and Humanities Research Council has seen fit to fund my new project, ‘Forging Memory: Falsified Documents and Institutional History in Europe, c. 970–1020’. This aims to place forgeries at the heart of our understanding of the growth and development of historical consciousness at a key period in European history. Starting from the the deceptively simple observation that the later tenth century is the first time when the forging of documents can be attested across the Latin-speaking West, it seeks to investigate what this meant on the ground.

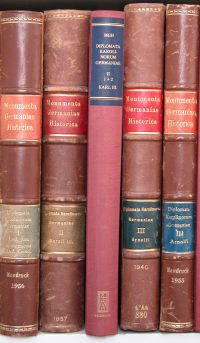

Medievalists have, of course, long known that falsified documents can be just as interesting as the real thing. Nevertheless, forgeries continue to receive less attention than their authentic counterparts. In part, this is a matter of inertia. Particularly when using older editions, it is all too easy to slip into the tendency of ignoring those marked up as ‘forged’ (conveniently relegated at the back of the volume, in the case of the older Monumenta Germaniae Historica editions). More to the point, perhaps, forgeries often lack context. Whereas we know a fair bit about where and when most authentic documents were produced, it is difficult to ascertain the same for forgeries – documents which by their nature seek to hide their true origins. Studying them therefore requires a great deal of contextual knowledge about the forger and his (or her) aims, a fact which has discouraged synthesis and generalization.

Still, when we can date and localize forgeries, they offer a wealth of information. Precisely because forgers were not constrained by the realities of their day, these documents tell us much about their hopes, dreams and ambitions; they were the blank canvases onto which the monks and clerics of the Middle Ages projected their ‘ought world’ (to use Karl Leyser’s memorable turn of phrase). In this respect, we are lucky to have a number of closely datable forgery complexes from the later tenth century. Five of these will form the basis of my investigation, which will result in a book-length study: the counterfeit diplomas and papal bulls of Pilgrim of Passau (970s); the Worms forgeries, associated with Bishop Hildibald (980s); the purported papal privileges of Abbo of Fleury (990s); the Orthodoxorum charters, concocted under the auspices of Abbot Wulfgar (mid- to later 990s); and the forged and authentic diplomas associated with Leo of Vercelli (late 990s).

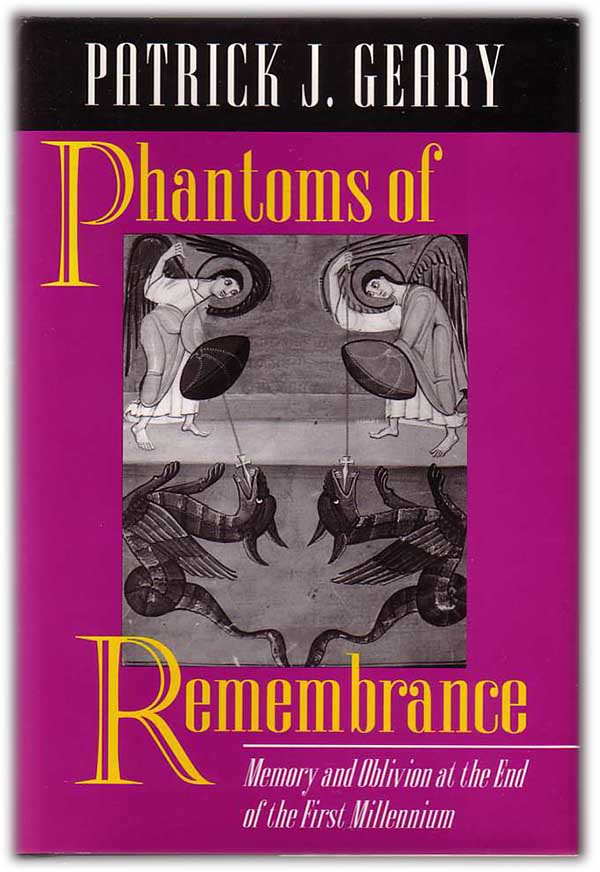

The intention is to use these case studies as a springboard to consider broader themes of memory and institutional identity in these years. They have been selected in order to give maximum geographical range within a tightly defined period; they have also been selected to give a balance of monastic houses (Fleury, Abingdon) and cathedral chapters (Passau, Worms, Vercelli). Each forgery complex is unique; and I hope to give due weight to the specific as well as the general. By examining a range of cases, however, I also hope to avoid getting lost in the detail. The interest of these documents lies in the fact that each act of forgery was not simply one of wishful thinking (though it was often this too); it involved a creative engagement with the past, the formulation of an alternative history of the religious house in question. By examining this phenomenon at the turn of the first millennium – a period identified by Patrick Geary as a decisive one where attitudes to the past are concerned – the study will add depth to our understanding of these developments.

In pragmatic terms, the project will run 21 months (effectively two years), with the first nine of these spent on archival research. Thereafter, the focus will be on writing up and disseminating findings, with a strong public outreach element. During this time, I will organize panels on the subject at a number of international conferences. The project will be then capped off with a public exhibition at the local cathedral in Exeter, which boasts its own fascinating collection of forgeries of the mid-eleventh century. This will be complemented by an end-of-project conference here at Exeter on ‘Forgery and Memory between the Middle Ages and Modernity’. Anyone interested in getting involved is strongly encouraged to get in touch!

One response to “Forgery comes to Exeter!”

Sounds like a great project, and my warmest congratulations once again on winning this award. I am looking forward to the public exhibition at the cathedral.