The Past Harvests Project

The Past Harvests Project

Posted by es970

16 February 2026Was life simpler for farmers in the past, in a world without huge, complex machinery, agribusinesses, agrichemicals and pesticides, genetic engineering, and the many and various interventions by central government, never mind international regulations? Yes, but our Past Harvests research project shows that life could still be very complicated in other ways.

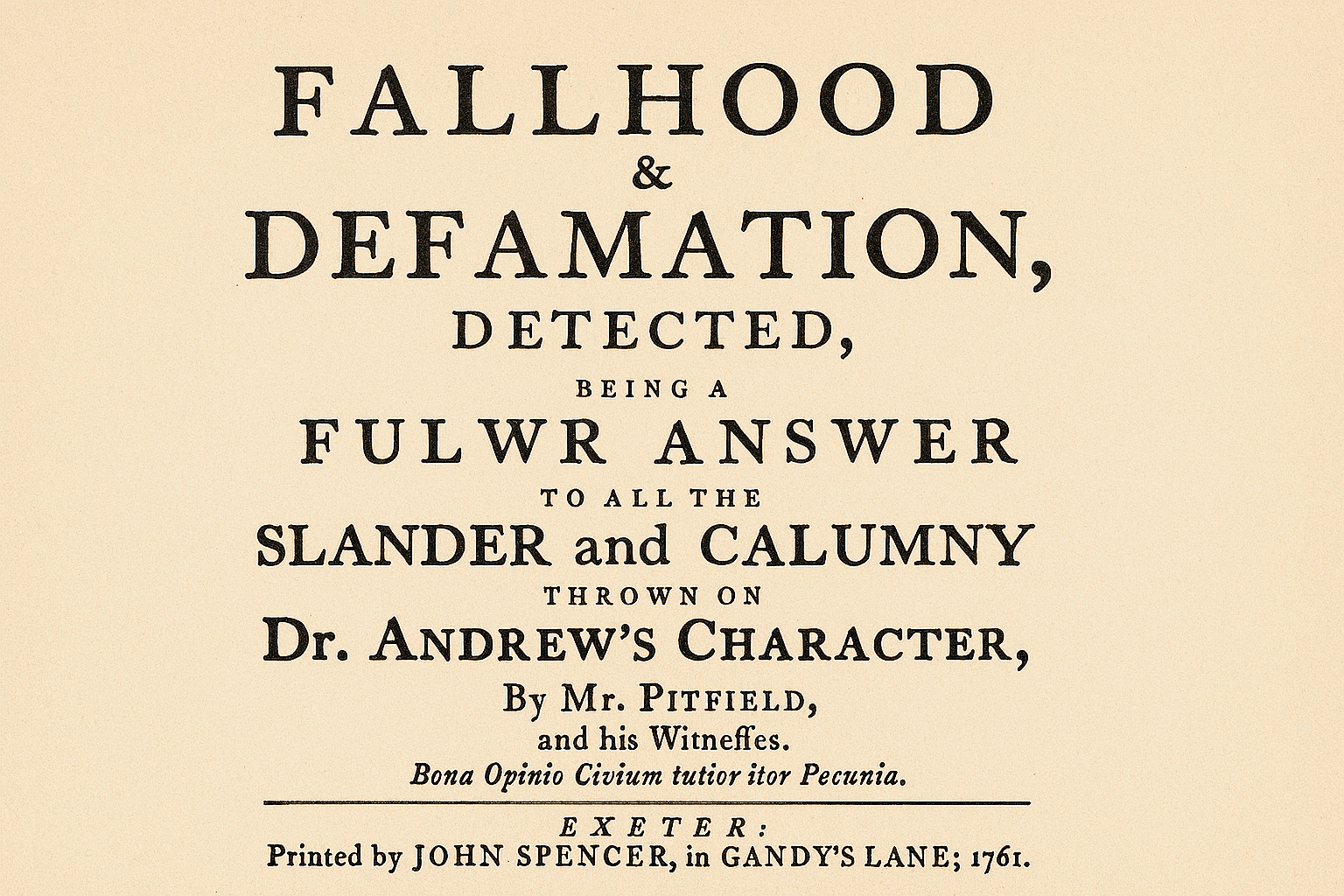

In 1759, William Pitfield, an Exeter apothecary complained to his friend (and fellow medical man) Dr Andrew about the tenant on his property of 7.5 acres of marshland in Alphington (just south of the city). He had bought his interest in the lands for £800, and although it was supposed to produce £63 per annum, the tenant, John Shillabeer, rarely paid more than half that sum. In response, Dr Andrew offered to buy it from him, but (obviously) wanted to know the price. That simple question set in motion two formal valuations, a public arbitration over two days in an Exeter inn, and publication of at least eight wordy pamphlets by various protagonists, plus associated mud-slinging in the local newspaper.

Why? The difficulty was that Pitfield did not own the property outright. Instead, like all other ‘tenants’ of the manor of Alphington, he owned a lease, which ran for three lives or 99 years. When he had bought it sixteen years earlier he had named himself (he was then 36 years old), and his two sisters, Mary (then 38) and Signata (then 40) on the lease. Signata seems to have died by 1759, and William wanted Dr Andrew to provide an annuity for himself and his sister – in effect, the same income from the property, without the bother of extracting rent from a reluctant tenant. But what was such an annuity worth? Obviously, it had to reflect the ‘value’ of the lives of William (now aged 52) and his sister (now aged 54), and their likely life-spans, but it also had to include the income-generating potential of the land itself. Was that the £34 or £35 that William could drag out of Shillabeer, or the £63 that the lease should have produced? The local custom was that the final value was the former, multiplied by the latter. On top of this, the actual, legal, freehold owner of this estate (Viscount Courtenay of Powderham Castle) would levy a ‘fine’ when the property changed hands, based on this calculation, as well as a ‘heriot’ (inheritance tax – just saying…).

So, working out what the value of these interests routinely took potential purchasers into the realms of actuarial mathematics, complex calculations of the net value of the property (excluding taxes, payments to the freehold owner, and the value of the ‘fine’ over the term of the lease), as well as trying to estimate whether they could extract more value to improve the yield, and thus lower the burden of these other costs across the lease term. No wonder it generated so much vitriol in this instance. On top of this, if you thought you had been too optimistic, you could (like William Pitfield) try to get out of the deal by selling on your interest. On the other hand, if you felt that you had nice little earner, you could pay to add another life to your lease, which William could have done when his sister Signata died. You could also borrow against the value of these lives, and (eventually) insure them, too.

This was futures and options trading in land, which existed in a strange zone between the freehold owner (Viscount Courtenay), and the actual user of the land (John Shillabeer). Eventually, by the early/mid-19th century, most landed estates either bought out these leases, or let them expire, and rented the land directly. They had decided that living in the past was much too complicated!

This blog was provided by Professor Henry French, Lecturer in Social and Early Modern History, at the University of Exeter and co-lead on the Past Harvests project.