In this interview, Catherine Hurcombe speaks to Dr Laura Sangha from the Department of Archaeology and History about her role on the research project, The Material Culture of Wills, England 1540-1790, which invites members of the public to explore the culture behind early modern wills through citizen science, workshops, and musical performances inspired by these historical stories.

CH: Would you like to start by introducing yourself?

LS: I’m Dr Laura Sangha. I’m an Associate Professor of History, and my area of expertise is 16th and 17th century history of England.

CH: What made you want to include this public facing element in your work?

LS: When you’re an early modernist, there’s already an appetite out there for learning more about the period, particularly because people are so interested in the Tudors. And you can use that existing interest to expand people’s awareness.

And for the research I’m doing with early modern wills, many people have encountered and become fascinated by historic wills already when researching their family history, so you can, again, use people’s existing interests to get them to think about our understanding of our own society.

CH: The wills project has included quite a few public elements so far: how would you say this has supported the research itself?

LS: Engagement with the public is central to how we’re creating our data. We’re using AI technology, and applying it to 25,000 wills, but the transcriptions the software generates do have some errors. So we are crowdsourcing the skills to correct this data on Zooniverse, one of the biggest online citizen science platforms in the world.

What we were very aware of at the start of the project was that we didn’t want to merely exploit people who generously gave their time to the project – it’s important for us to be giving back too. One of the project postdoctoral research fellows, Dr Harry Smith, is the architect of the Zooniverse site, and he spends quite a few hours every day talking to volunteers. And it’s a great way for us to learn from volunteers – people tell us just as much as we tell them!

The leader of our wills project is Professor Jane Whittle, and she built time into our work plan that would allow me, alongside our other postdoc, Dr Emily Vine, to manage the volunteer community and keep them engaged. There’s dedicated time for doing that within our workplan; it’s not just been bolted on at the end.

CH: It’s also quite emotionally charged, so that’s presumably something you need to take into consideration. For some people, it’s easy to stay detached looking at historical documents, and for others, you do get quite emotional!

LS: In some ways, as early modernists, we benefit from looking at people who lived a very long time ago, so you feel that distance a bit more. But absolutely – some of these people are writing wills as they reach the end of their life, and the material is often sensitive. One of the years in our sample is a plague year, so it’s a very traumatic time. These people are thinking: I need to write my will now because next week might be too late. Those are very evocative documents, so getting the tone right is important, making sure you respect the dead and their wishes, regardless of how long ago they lived.

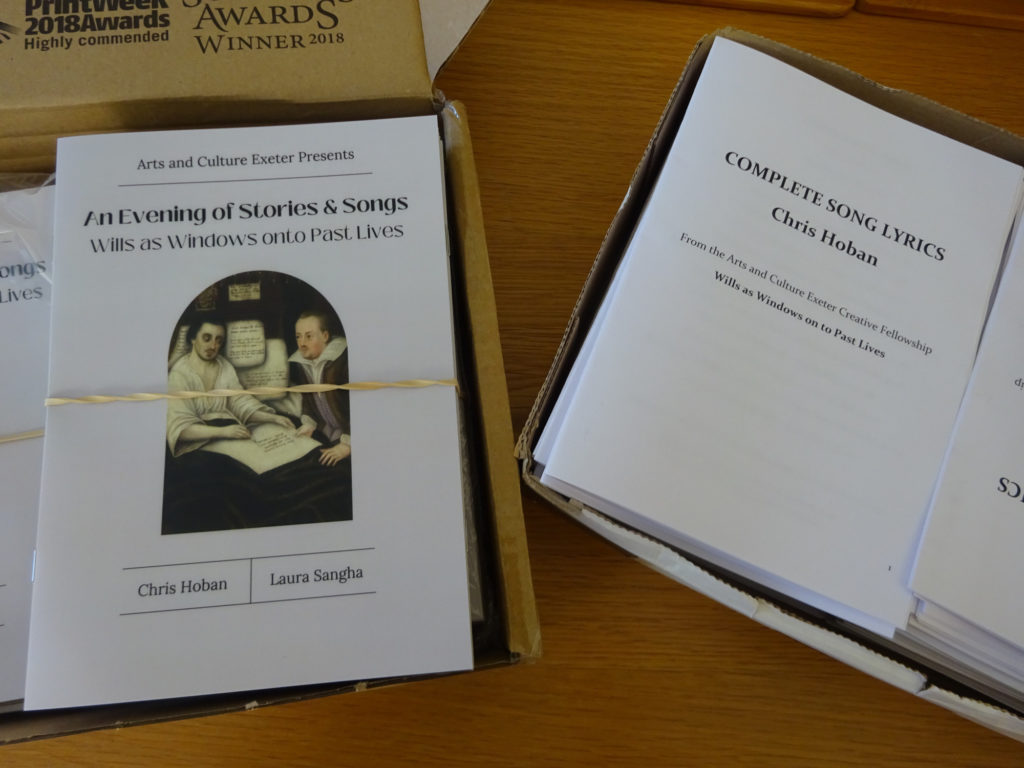

Related to this, I’ve been working with Chris Hoban, a musician and creative practitioner, and he wanted to think of what we were doing as a three-way dialogue: me, him, and the testators. This has been transformative for me, because as a historian sometimes you can fall into seeing your evidence as just data or information, so it’s useful to be reminded that these are people’s lives that you’re talking about. And that brings added dimension to our engagement with our sources.

CH: I like that idea of engaging with the modern audience, and historical audience as well!

You’ve got a lot of irons in the fire already – are there any other engagement activities you’d like to try, or communities you’d like to encourage to participate?

LS: Absolutely, lots of irons in the fire and not sure which direction we’re going to go with!

It would be nice if we could give some wills to people and get them to tell us what they think, rather than us telling them how a historian would approach it. And we’ve got various ideas about how we might do that.

In terms of taking this to different audiences, we’d like to put these documents in front of schoolchildren and invite them to think about the themes that are raised. There’s potential for using that both to do a bit of history but also lead into discussions around grief and bereavement.

We’re also thinking about solicitors. Lots of adults in the UK haven’t made a will, so there’s an opening for us to show people wills and encourage them to sort out their own, and then here’s some local solicitors for you to do that!

CH: What would your advice be to anyone undertaking public engagement activities – particularly incorporating topics like this, that could seem more taboo or uncomfortable?

LS: One of the most useful things you can do is talk to people that have done it already, because there are lots of people well-versed in doing public engagement around difficult topics. Also letting people know that they can opt out and that no one’s judging anyone!

CH: Absolutely, setting up a dialogue and including communities in those conversations from the beginning.

LS: Engaging with the public, people will ask questions you haven’t thought of.

You’re collaborating, not telling – it’s a dialogue. That can really enrich what you’re doing as a historian: getting that broader perspective and bringing it into what you’re doing does improve it.

You can read more about the public engagement work behind this project here. If you’d like to see this in action, free tickets are now available for ‘Stories and Songs: Wills as Windows onto Past Lives’, which will be taking place as part of this year’s FUTURES Festival.