Pustules, Palaeogenetics and Pandemics from Galen to Rhazes: How to do the Early History of Smallpox and Measles

Members of the STAMP Research Centre are involved in an exciting interdisciplinary project—funded by a Wellcome Discovery Award which is just getting started. Rebecca Flemming, Dan King and David Leith are collaborating with Nahyan Fancy and Siam Bhayro from the Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies in the core team.

The focus of the project is a multi-layered investigation into the history of smallpox, measles, and similar feverish, pustular infectious diseases in Afro-Eurasia from the second to the tenth century CE. Beginning, that is, with the copious surviving writings of the preeminent physician of the Roman Empire, Galen of Pergamum, including engagements with the ‘Antonine Plague’ the terrible pandemic which swept across Roman territory from the late 160s CE onwards, and discussions of many other serious illnesses characterised by fevers, rashes, spots and pustules (amongst other signs). We will collect and analyse all Galen’s references to what he calls ‘the great’ or ‘long-lasting plague’ (loimos, a generic Greek term which covers all large-scale and lethal outbreaks of sickness)—and compare the pestilential symptoms with those which signify specific named diseases such as ‘anthrax’, ‘erysipelas’, and ‘lichena’, all conditions which manifested both on the skin and inside the body, and in the case of ‘anthrax’ were also known to take epidemic form. We will explore Galen’s aetiologies for these ailments, how he understood their similarities and differences, and also put these ancient accounts into dialogue with modern disease descriptions. The Antonine Plague has been identified with modern small-pox, for example, though the match is not perfect by any means, and ancient ‘anthrax’ clearly correlates with its current namesake, but the other ancient conditions are much harder to map onto present pathologies.

Next, we will trace this ancient pathological typology through the multilingual medical texts of the late antique and early Medieval Mediterranean and Middle East, through encyclopaedic traditions, commentaries and summaries (jawāmiʿ) in Greek, Syriac, Latin and Arabic. Do these disease concepts persist? In what ways do they shift and change? Are there new discussions of pestilence? How are the names and terms found in Galen rendered in different languages?

Both Galen and many intervening authors’ writings fed into the work of the eminent physician of the Abbasid Empire, Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (latinised as ‘Rhazes’). Rhazes’ synthetic Maqāla fī al-judarī wa al-ḥaṣba, composed around 900 CE, is usually translated into English as Treatise on Smallpox and Measles and acclaimed as the first surviving text to comprehensively describe and distinguish these two diseases. Likely if any of the earlier Syriac or Arabic compendia survived, Rhazes’ tract would seem less decisive, but it certainly settled and entrenched a terminology and typology around these ailments in learned Arabic medicine, embedding them in an established set of explanations and therapeutic repertoire. The team will produce the first modern critical edition of Rhazes’ Maqāla, in dialogue with the relevant sections of his huge Kitāb al-Ḥāwī (‘The Comprehensive Book’), a medical compilation of enormous proportions, collecting extracts from previous medical works meshed with notes and ideas from his own experience and practice.

For Rhazes both judarī and ḥaṣba were essentially childhood diseases, endemic in the pathological landscape he operated in. How far back can these ideas be traced in the works he quotes? What kinds of epidemics and plagues feature in Rhazes and these earlier Arabic and Syriac medical writings? What clusters of symptoms characterise and distinguish the different diseases, how do they relate to each other and their past iterations? And, how do they compare with modern disease descriptions? It has certainly been argued and assumed that Rhazes judarī strongly resembles—with the requisite shifts in emphasis and detail—modern smallpox and his ḥaṣba strongly resembles modern measles. We will, therefore, work backwards from Rhazes, following his citations of earlier authors to map out a set of terminological, conceptual, classificatory and practical trajectories reaching back to the second century CE, all the while placing his own work within his contemporary context.

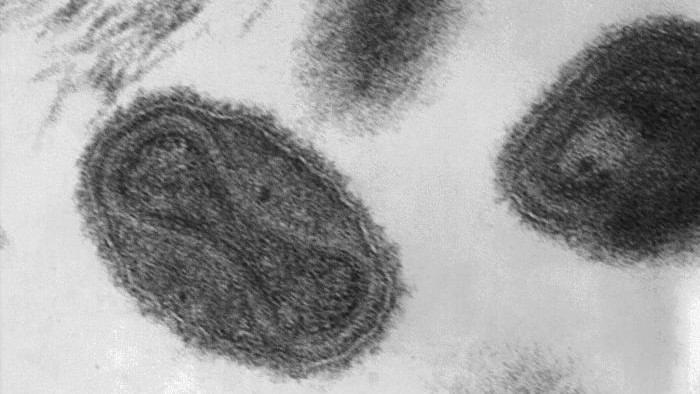

It is not just ancient and medieval medical texts that have a role to play in constructing the history of past diseases and pandemics, other surviving writings, and a range of archaeological material, from skeletal remains to votive offerings, amulets to buildings and burials also have key contributions to make. Palaeogenetic studies on past pathogens have exploded on to the historical scene, especially over the last decade. Though Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes bubonic plague has received the bulk of attention so far, some palaeogenomic data on the evolution of the variola virus (VARV), the causative agent of modern smallpox, has been published, amongst other relevant studies, including one historic (early twentieth century) genome of measles morbillivirus (MeV), a more fragile RNA virus. These are exciting developments in a rapidly moving field, providing new data for the history of diseases and societies, and for the understanding of microbial evolution and changing pathological ecosystems, while raising a host of conceptual and methodological questions. What exactly does the new genomic evidence mean? How are the novel findings best combined with written sources and other archaeological material and scientific data? How does the inherent—and sometimes rapid—genetic changeability of pathogens impact our understanding of the notion of disease itself and of particular infectious diseases?

All of these types of evidence, as well as modern epidemiology and more speculative models of pathogen evolution, will be involved in this project. An important strand is explicitly interdisciplinary and focuses on methodology. It will take into consideration this range of material, data and arguments, and the different disciplinary practices that produce them, putting them all into conversation to address the question of how the different types of evidence fit together are best combined to generate the fullest and richest understanding of past societies and their diseases, and of past diseases and their socio-ecologies. This is not only crucial to comprehending wider historical patterns but also to current scientific research into human health and illness.

Reading

- Rhazes, 1848. A Treatise on the Small-pox and Measles. Translated from the original Arabic by William Alexander Greenhill. London: Sydenham Society.

- Fancy, Nahyan. 2022. ‘Knowing the Signs of Disease: Plague in the Arabic Medical Commentaries between the First and Second Pandemics’, in Lori Jones and Nükhet Varlik (eds), Death and Disease in the Medieval and Early Modern World: Perspectives from across the Mediterranean and Beyond. Martlesham: Boydell & Brewer, 35–66.

- Flemming, Rebecca. 2023. ‘Pandemics in the ancient Mediterranean’, Bibliographic Essays on the History of Pandemics: An IsisCB Special Issue 114, Number S1: 288-312.

- Flemming, Rebecca. 2018. ‘Galen and the plague’, in C. Petit (ed.), Galen’s Treatise Περὶ Ἀλυπίας (De indolentia) in Context. Leiden: Brill, 219-244.

- Green, Monica. H. 2024. ‘The Pandemic Arc: Expanded Narratives in the History of Global Health’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences,79: 345–362.

- Mühlemann, B., et al. 2020. ‘Diverse variola virus (smallpox) strains were widespread in northern Europe in the Viking Age’. Science 369(6502), eaaw8977 (no pag).

- Zhao, H. and Wilson, A. 2025. ‘A case of osteomyelitis variolosa from Roman Britain, and the introduction of smallpox to the Roman world’, Journal of Roman Archaeology 38: 1 – 32