Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Exeter Collaboration for Academic Primary Care (APEx) Blog

Posted by ac1516

27 August 2025

The 10 Year Health Plan for England was published in July 2025, as part of the government’s mission ‘to build a health service fit for the future’. In the first of our collaborative blogs, members of the Primary Care Delivery theme at APEx reflect on aspects of the ‘3 radical shifts’ set out in the plan (hospital to community, analogue to digital, sickness to prevention) in relation to current projects and networks.

A core aim of the APEx Primary Care Delivery theme is to conduct research that is driven by the priorities of patients, the public and practitioners as well as health and care providers, and reflects the needs of policy makers at local, national and international levels. Here, we showcase some of our current work and consider opportunities for future multidisciplinary research, working alongside key stakeholders including patients, caregivers and members of the public, to evidence this call for rapid changes within the NHS and ensure equitable, inclusive primary care for all.

Table of contents:

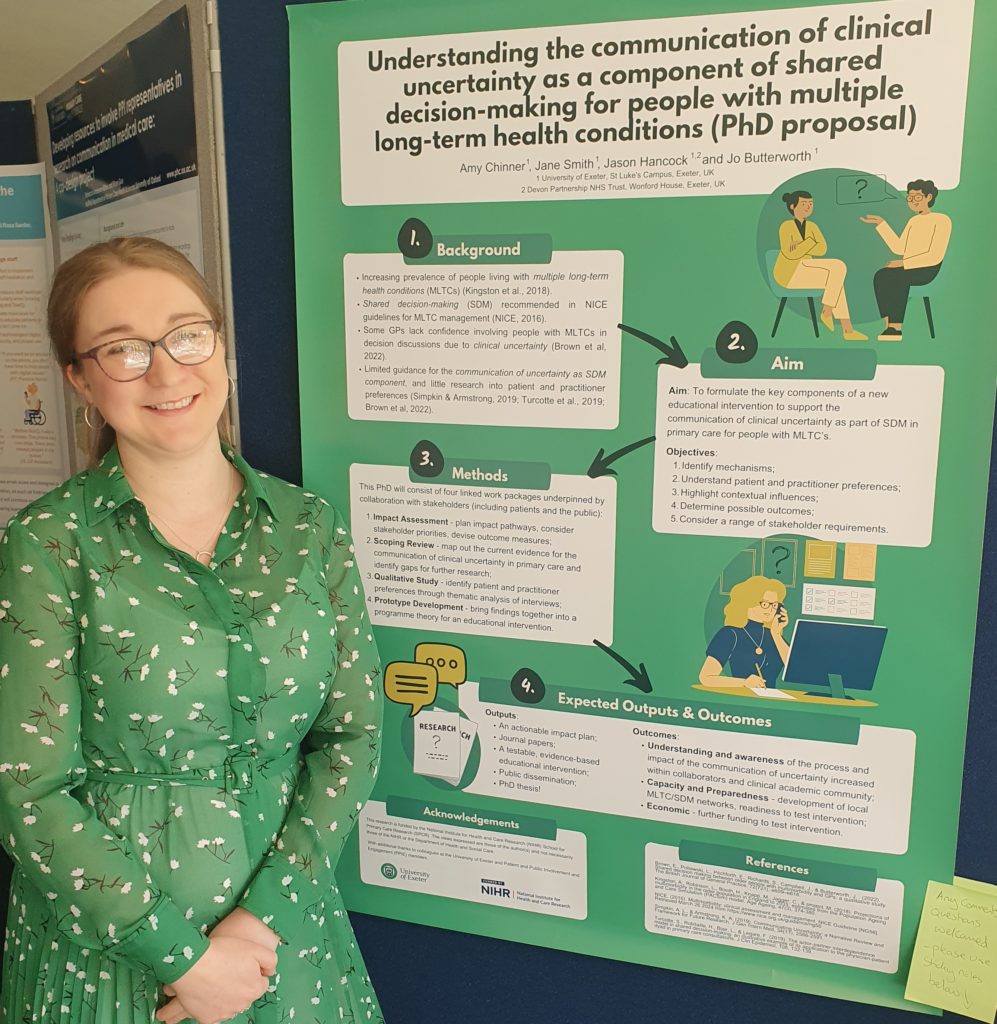

Amy and Jo kick off by reflecting on the shift from hospital to community, providing insights from our research into patient-centred care for people living with multiple long-term conditions. Amy’s frustrations that the plan fails to explicitly mention patient involvement in decision-making about their care reflects an internationally recognised challenge for researchers seeking to evidence the benefits of patient-centred approaches, including shared decision-making and continuity with the same practitioner. Jo is part of an international collaboration to develop a core outcome set for shared decision-making to address this and, later, Nada outlines her work on measures of continuity.

“I am currently working on a PhD (funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research) to understand the communication of uncertainty as a component of shared decision-making (SDM) for people with multiple long-term health conditions (MLTCs) in primary care. SDM is a collaborative process whereby patients and their healthcare providers work together to jointly make healthcare decisions, so I was interested to see that promoting patient choice is a key theme within the new NHS 10-year plan. However, I found it surprising that there is a lack of consideration of how to support patients with making informed healthcare-related decisions, with the focus instead on providing patients with more medical information via an app to ‘ensure there are always 2 experts in every consulting room’. This conflicts with the point central to SDM that patients already bring invaluable expertise to consultations; an understanding of what is important to them within the context of their lives. Additionally, just providing people with more information without transparent communication about the limitations (and so uncertainties) of that information, or consideration of what this means in line with an individuals’ needs, values and priorities, is short-sighted at best. So, watch this space as we investigate the process and impact of the communication of uncertainty as part of SDM in primary care!”

“I would like to think that care happening ‘as locally as it can’ and only ‘in a hospital if necessary’ will benefit those with complex needs, such as those living with multiple long-term conditions (MLTC), who otherwise have the burden of attending multiple appointments to specialists operating in silos. However, if care should happen ‘digitally by default’ to enable provision ‘in a patient’s home if possible’, could this drive inequality in digital access for patients who struggle with IT or health literacy, for example? Under co-supervision with Vicki Goodwin (who co-leads the Rehabilitation theme at APEx), our undergraduate intern is conducting an Equality Impact Assessment for our national research prioritisation project on Models of Care for MLTC Multiple Long-Term Conditions Cross-NIHR Collaboration | NIHR, working with stakeholders including a diverse group of members of the public, and raising considerations such as these to avoid driving inequality when we make our recommendations for research.”

In the Southwest, the population has unique needs with distinct factors contributing to care access, deprivation, and workforce recruitment and retention. This in turn shapes the direction of our research and our delivery of the research aims set out in the 10-year plan. Chris and Judit consider implications of the plan on remote and rural populations, the workforce, and our research.

“Most patient contacts take place in general practice, hence the pledged focus shift of healthcare from hospital to community is welcome. The 10 Year Health Plan promises the creation of a Neighbourhood Health Centre in every community, starting with the most deprived areas. “Social justice runs through this plan” – there is acknowledgement of the social determinants of health and emphasis is placed on addressing the social gradient. It is pledged that funding allocation to general practice, via the Carr-Hill formula, will be reviewed, to determine how health need is reflected by the current funding arrangements. It is well recognised that general practice workload is higher in areas of deprivation, workforce and need-adjusted funding is unevenly distributed between practices in affluent and deprived areas. Multimorbidity is more prevalent in deprived areas, and there is more complexity arising from the combination of physical health problems, psychological and social burden. Therefore, inequality exists not within the population only practices serve, but between practices too. Grassroot movements are important and powerful – our Deep End Cornwall network was established in 2022 to highlight and help to tackle the local inequalities, and to contribute to a now international Deep End movement Deep End International Bulletin No 13. There is a wealth of experience relating to care organisation in practices serving deprived areas, which is based on their in-depth knowledge of their local population. This experience can be safely relied upon when setting up the Neighbourhood Health Centres. We recently found that it is not always possible from published literature to determine how new approaches work best in affluent and deprived areas Early cancer diagnosis and community pharmacies in deprived areas — NIHR School for Primary Care Research. I read with interest in the 10 Year Health Plan that there is an emphasis on wearables to contribute to healthcare. In our new project lead by the European Centre for Environment and Human Health, we will be looking at the use of home environment sensors.”

“To its credit, the 10 year plan mentions rural populations eight times – a significant improvement on the single unfulfilled promise of the 2019 Plan regarding rural hospital services. It’s good that the new plan recognises that those who live in rural and coastal areas, alongside other disadvantaged groups, experience worse NHS access, potentially worse outcomes and die younger. Importantly, it also acknowledges that one size does not fit all and that service offers will differ according to local needs. But there’s so much we don’t know: How will the neighbourhood health service model restore GP rural access? Only, surely, by reducing demand. How can that be achieved without employing more GPs (and more staff to other roles) to address the demand. Where will these new GPs come from and why aren’t we already employing them? Recent trends have shown disproportionate loss of rural practices through closure or merger (with subsequent loss of rural branches) leaving rural dwellers with longer travel times and reduced access to primary care. My worry is that, if the new neighbourhood health centres attract staff from practices, this can only add to the significant and particular recruitment and retention challenges faced by rural practices. I also see that the introduction of multi-neighbourhood providers will probably mean that some services are centralised to locations more distant from rural practices than current care settings. Moving services further away from a rural population will predictably worsen rural healthcare exclusion. The emphasis on transition to a digital health service also poses particular challenges for rural populations, who are generally older with lower educational attainment than their urban counterparts. Older age and infrastructure factors, limiting broadband and mobile signal access, mean that rural dwellers are more likely to be digitally excluded. The other snag with the “digitally by default” policy is that the plan does not provide resources staff to support patients in developing the skills and confidence that they will require to use digital healthcare. Therefore, there is a risk of widening digital health inequality for rural residents. So many questions remain needing detailed answers. The commitment to local solutions to service delivery is promising but will need to be proven in practice if the rural population of England are to benefit rather than be further disadvantaged.”

Below, Primary Care Delivery theme member, Bethan, balances enthusiasm with caution about the digital shift. Bethan emphasises a need for primary care delivery to include safeguards against online health-related misinformation. Gary highlights the importance of our work on digital facilitation, tackling the risk of inequality in access to care by supporting both primary care staff and their patients.

“Reading the NHS 10-Year Health Plan, the most exciting element for me is the commitment to digital-first primary care. The proposed “doctor in your pocket” NHS app, which will bring together appointment bookings, AI-supported GP consultations, and access to a unified patient record, could transform how people engage with health services. If implemented effectively, it promises faster, more streamlined, and more accessible care. However, people’s health information journeys rarely begin and end with official NHS platforms. Many turn to social media communities, condition-specific forums, and online discussion spaces to share experiences and to seek advice, and this has been the case for decades, although we have seen a rapid increase in use of such sites in recent years. While these spaces can offer valuable peer support and empower users to take the lead in self-managing their health, my NIHR SPCR fellowship research shows that online social communities are also fertile ground for spreading health-related misinformation, undermining patient safety, trust and health behaviours. The problem of online health-misinformation has not featured in the 10 Year Health Plan, despite growing concern from health care professionals and researchers regarding the accuracy and safety of some health information online. Through my fellowship research, I argue that the need to address online health-related misinformation must become central to digital primary care, and plan to further explore how we can facilitate this, whether through establishing clinician engagement in moderating online content, guiding routine discussions/shared decision making in consultations around use of online social communities, or integrating trusted online social sources in the NHS app and digital pathways. Only by weaving digital innovation with safeguards against misinformation can the NHS genuinely empower patients and reinforce its vision for a prevention-oriented, community-centred future.”

“From analogue to digital includes both the back-room workings of the NHS, new tools for clinicians to use in patient care, as well as a big focus on the patient facing gateway to NHS services. The plan sees this digital gateway as a mechanism to reduce the barriers some patients face in accessing services. Examples given include providing tools for those with hearing or sight impairments, and the ability to tailor information to different patient groups with different needs. These are great things to see and can only be welcomed. However, while the plan does acknowledge that there will be patients with lower digital literacy that will need support, it says very little as to how this will be done. Indeed, it says almost nothing about how staff in the NHS will be provided with the skills to use digital services themselves and how they will be enabled to help patients to use them. Our work on the Di-Facto project showed that many staff members working in primary care did not feel equipped to support patients in using online services, but as the NHS becomes ‘a fully digitally enabled service’ this support role will increasingly fall to those on the front line. We are in the process of designing a Di-Facto follow-up study to address this need head – watch this space!”

APEx researchers who bridge the Primary Care Delivery and other APEx themes (Long-Term Conditions and Mental Health) are also actively shaping the shift from analogue to digital:

Jane explains why the shifts outlined in the NHS 10-Year Health Plan will only be delivered if the primary care workforce is developed and supported to deliver change, outlining the importance of ongoing collaborative research to understand the impact of new roles within the workforce and to support the wellbeing of primary care practitioners. Nada seeks a means of measuring the improvements in continuity of care that are hypothesised outcomes of improvements to access and digital services set out in the 10-year plan. Nada also describes research that will focus on clinical pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, seeking to provide an understanding of the impact of these roles on continuity of care.

“A diverse, healthy and sustainable workforce in primary care will be central to implementation. There has been a recent expansion of additional roles into general practice teams and we have been involved in mixed-methods work led by colleagues in Oxford to assess the contributions and impacts of these additional healthcare workers on practices and patients (CARPE project) as well as exploring some of the challenges faced by those in newer, less well-defined roles, such as Social Prescribing Link Workers (e.g. Tierney et al 2025). Poor workplace wellbeing is a threat to retention and recruitment of healthcare staff and high-quality patient care in all settings, but general practice has been particularly affected. With colleagues from the Exeter-led Care Under Pressure research programme we have therefore conducted a preliminary Primary Care Under Pressure (PCUP) study to map wellbeing strategies and services available to the general practice workforce in England. We found that it was unclear where the responsibility for general practice staff wellbeing lies and despite identifying a large number of available services, most appeared reactive to problems and targeted individuals, rather than systemic workplace issues. We aim to build on these findings, identified areas of good practice and results from a review of evidence on wellbeing interventions for primary care staff with which other APEx colleagues are involved to plan a programme of research to improve and evaluate the impacts of wellbeing support to ensure a healthy and sustainable primary care workforce for the future.”

“Continuity of care matters to patients, and clinicians. The NHS 10 year plan highlights how improvements to access and digital services can improve continuity of care especially for those with the most complex care needs. A key policy shift towards improving access has involved widening the multi-disciplinary team and offering more patient appointments with a range of health care professionals in general practice. Our Pharm-Connect project is looking at the impact of these different multi-disciplinary roles, focussing on clinical pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, and how these roles impact on continuity of care from the perspectives of patients and health care professionals. We also want to look at how better to measure continuity of care across multi-disciplinary teams to help practices understand the impact on patients. Faster access to care is sometimes seen as a challenge to continuity of care, but we know there are practices that can offer high levels of continuity of care, with good access and high levels of patient satisfaction. The Re-CONNECT project will take a deep-dive, through a realist lens, at a sample of these practices with high levels of continuity of care, to understand how they are able to run their systems and provide better continuity of care to their patients. We hope this project will inform ways in which other practices can offer better continuity of care while meeting the high access demands in today’s NHS.”

Rachel and Judit bring perspectives on the role of community pharmacists as set out in the plan, as well as highlighting research on the role of community pharmacists in early cancer detection. Tom discusses the need to focus on the management of clinical complexity and uncertainty to support advanced clinical pharmacy practice roles in primary care.

“The planned increasing role of community pharmacy is clear from the 10 Year Health Plan. This follows several initiatives that have already been introduced, such as the Community Pharmacy Consultation Service and the subsequent Pharmacy First programme. The scope of Pharmacy First is to provide consultation opportunities and offer treatment for seven minor illnesses. Therefore, pharmacists in community pharmacies are now delivering significantly more clinical services. The plan sets out an increasing role for community pharmacies in the management of long-term conditions and prevention. Our recent research has looked into their role in detecting cancer early Early cancer diagnosis and community pharmacies in deprived areas — NIHR School for Primary Care Research. Community pharmacy has become more integrated to general practice since the introduction of Primary Care Networks. According to the plan, pharmacies will become integral to the Neighbourhood Health Service. These hubs will be first developed in areas of deprivation. The number of community pharmacies has declined in recent years, and this decline is more pronounced in deprived areas. There are widely reported issues with funding, workforce and workload. Therefore, it will be a challenge to introduce new services under the circumstances, while the ability to link data within a single patient record is welcome.” (written by Rachel and Judit)

“The 10 Year Health Plan makes overt references to developing advanced models of practice for healthcare professionals, encompassing allied healthcare professionals, nursing and pharmacy roles in the NHS. As clinicians from different backgrounds begin to move towards delivering care autonomously for multimorbid and complex patients, the management of clinical uncertainty will be increasingly important for these clinicians. In the recent publication of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Advanced Pharmacy Practice Curriculum, the ability to manage complexity (and the inherent associated uncertainty) is a core competency that pharmacists progressing in these advanced roles will need to demonstrate. My research is rooted in my own clinical experience of reviewing complex polypharmacy as a primary care pharmacist. PPhoCUs: Polypharmacy, Pharmacists and Clinical Uncertainty explores how pharmacists navigate clinical uncertainty when reviewing polypharmacy and what the patient experience of pharmacist-delivered care is in general practice. Understanding how uncertainty can be navigated and mitigated in medication reviews could result in better outcomes for patients, appropriate deprescribing and better multidisciplinary working in practices. I am excited to see how our findings from PPhoCUs will translate into supporting advanced clinical pharmacy practice in primary care.”

Phil conveys a perspective from his role co-leading the primary care research programme in the NIHR Research Delivery Network (RDN). Mary provides an example to illustrate that the reality of translating policy and guidance into clinical practice can be challenging.

“We welcome the increasing focus on primary and community care within the 10 Year Plan. We would expect this to deliver more opportunities for GPs, their teams and other primary care professionals such as pharmacists to become more engaged in delivering NIHR research studies. In addition, we would expect the other two shifts of analogue to digital and sickness to prevention to further stimulate the development of research studies and clinical trials that are digitally-enabled and tackle prevention, which is at the heart of the GP’s role. Research-active GPs also have a role to play in ensuring that the UK meets the Prime Minister’s 150-day target for set up of clinical trials by March 2026. This is one of a number of initiatives to attract more industry clinical trials into the UK including the Primary Care Commercial Research Delivery Centres (PC CRDCs) which are due to come on stream in November 2025. The Kings Fund recently referred to a fourth shift defined as needed by Wellcome i.e. from research to reality. It is intended that this shift will embed research and innovation to create an NHS fit for the future.“

“In the hospital to community section of the Plan, a public participant describes his mother’s ‘frustrating journey’ to obtain dementia care and support. It certainly struck a familiar chord with me. Our recent mixed methods research about prescribing for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in general practice has found that many people with AD may face inconvenient and unnecessary referral to secondary care as they progress to the moderate-to-severe stages of the disease. This is in part due to a discrepancy between national (NICE) and local formulary guidelines for care of people with AD. Although NICE guidelines promote a greater role for GPs in the pharmacological care of people with moderate-to-severe AD, local formularies continue to recommend re-referral to specialist services for treatment initiation for this group. We assessed GPs’ attitudes towards possible changes to existing care pathways and found a considerable gap in GPs’ knowledge, skills, and confidence which must be bridged to enable them to respond to their patients’ evolving needs and to deliver the best possible pharmacological care as conditions progress. Professor Louise Allan and the team are hoping to secure further funding to address these issues through a programme of work with local formularies and general practices.”

Emma, head of the department for Health and Community Sciences, is focused on getting it ‘right’ in the delivery of the 10-Year Health Plan for England and learning from previous research and models of care. Emma aptly concludes our blog by conveying her excitement about the role that the APEx Primary Care Delivery theme can play in achieving this.

There are some welcome shifts indicated in the plan for those of us working in primary care. I am really interested though in seeing the delivery plan if it is published in the coming months. The 10 year plan lists a lot of ideas but how those will be delivered in ten years with current fiscal constraints and significant workforce challenges remains to be seen. The desire to shift care from hospital to community settings is not new. The previous NHS England long-term plan also had increased expectations of delivering more of what hospitals typically do in primary care settings but our work with the LSE-Lancet Commission on the Future of the NHS shift showed that workforce during this period increased far more in secondary than primary care. There is a lot to get right in terms of how these plans will be financed and delivered and how you ensure reimbursement models and incentives align to achieve the goals set out. From previous work on integrated care, I also find myself nervous about assumptions that shifting care to the community will be cost saving and help to contain demand. Increasing service provision in the community and collocating services has the potential to improve care for people but will typically see an increase in demand at a time when primary care is struggling. I like the idea of neighbourhood health centres in terms of the ‘one stop shop’ vision but we also know through previous research including around community hospitals and maternity services that health services are an important part of communities in themselves. As successive governments and policies come in, ideas are recycled even if presented as new. Through our research we have explored how we can learn from history to inform policy making and I am keen that we explore opportunities to maximise learning from previous models including around ‘one stop shops’ and GP led hospitals whether in UK or internationally. One thing I learnt from co-authoring the LSE-Lancet Commission on the Future of the NHS is the importance of research resulting in actionable recommendations and that this is best achieved in partnership. I am excited for the opportunities the primary care delivery group will have in co-producing such recommendations through our research to inform the implementation of the 10 year plan.

Emma Pitchforth