Posted by ah220

3 March 2021James Maxia, Eva Thomann and Jörn Ege find that there is a considerable implementation gap at UK universities of the ‘Prevent Duty’ introduced under the 2015 Counter-Terrorism and Security Act wherein university lecturers are legally required to identify and report any student they suspect may be undergoing a process of radicalisation. The results of a nationally representative survey suggest the Prevent Duty faces a severe acceptance problem at the frontline. Many lecturers find it difficult to reconcile the role that the Prevent Duty should play in their daily work with what they conceive to be their core professional values and tasks.

In September 2017, a teenager from Surrey, Ahmed Hassan, attempted to detonate a homemade explosive device during a failed terrorist attack on the London underground. In the aftermath of this incident, details surrounding the perpetrator’s participation in the government’s deradicalisation programme – Prevent – in the months prior to the attack prompted further public scrutiny towards the policy. In 2015, the UK government had enacted the Counterterrorism and Security Act, which introduced a statutory requirement for professionals working for education and healthcare institutions to undergo training in recognising signs of radicalisation and a requirement report anyone they suspect of being radicalised. The 2017 incident fuelled existing concerns and contributed towards casting doubt on Prevent’s overall effectiveness and legitimacy. Several vocational and societal groups have expressed strong opposition to the Prevent policy, arguing that it clashes with professional norms of confidentiality and encourages limitations on freedom of expression and discriminatory profiling. In 2016, a group of lecturers from the University of Manchester published a letter detailing their opposition to the policy and voicing concern for “the role of the lecturer, the sanctity of academic freedoms and intellectual curiosity” as well as the undermining of diversity on campus. These concerns were further echoed when in 2019 a judicial review of the Prevent Duty guidance issued to universities by the government found it to be in violation of free speech.

The Prevent policy was originally conceived in 2003 as part of the broader UK counterterrorism strategy (CONTEST) which is predicated on four main objectives: prepare for attacks, protect potential targets while pursuing and preventing terrorist activity (Ibid). The success of the Prevent strand rests on the ability to identify (potentially) radicalised individuals. While the Prevent Duty applies to a range of institutions, one important locus for its implementation are universities, where young individuals make key formative experiences. Among those newly tasked with implementing this duty are university lecturers, who are legally required to report any personal or classroom interactions that may indicate a student undergoing a process of radicalisation.

At first glance it may seem counter-intuitive to engage University lecturers, who have spent most of their careers doing research and teaching academic subjects most of which are unrelated to terrorism, in preventing radicalisation. However, the Prevent Duty is just one example of an ever-growing trend toward “new modes of governance” that involve actors from the private and voluntary sectors into the delivery of public policy. These actors are typically deemed to be in a unique position to help reach the policy goals (here: preventing radicalisation) better than any governmental actor could do it. University lecturers, for instance, interact regularly with students and, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, discuss topics with them that touch upon societal and political issues. They should thus be the first to notice if individual students appear to “go astray”. Asking them to report such individuals seems much more efficient and effective than sending police officers or social workers to campuses to look out for such individuals. What makes the Prevent Duty special, however, is its uniquely politically sensitive and contested nature. As the above mentioned events illustrate, not only its effectiveness, but indeed also its legitimacy are being questioned. But what do we really know about how Uk lecturers think, feel and act when implementing the Prevent Duty in their daily work?

Methodology

In our ongoing study, which has received ethics approval from the University of Exeter, we focus on the role of lecturers in implementing the Prevent Duty. We performed an anonymous online survey in November 2020, to which we invited all lecturers currently teaching at a Social Science or Humanities department at a UK university. We received 1005 responses of which 84.68 percent have a permanent contract at a UK university that involves some form of student contact. Our survey had three main goals. On the one hand, we sought to obtain information about the extent to which UK lecturers are informed about the Prevent Duty, and have made concrete experiences with its application. On the other hand, we confronted lecturers with a fictitious scenario of a student contact to get an impression of their willingness to actually implement the Prevent Duty the way it is intended. Finally, the survey helped us to learn about the attitudes of lecturers toward the policy.

Is the prevent duty effectively implemented at UK universities?

The good news first: the vast majority—86.34 percent—of the respondents have heard about the prevent duty. Moreover, the majority—59.08 percent—are at least somewhat familiar with the Prevent Duty regulations for UK universities. However, a surprisingly large percentage of the lecturers (62.41 percent) report to never have received training on the Prevent Duty. Most of those who do report having received training describe it as being “self-guided material provided by the university” (66.93 percent), as opposed to actual workshops or meetings. We further asked lecturers whether they have ever been in a situation where they believed the Prevent Duty could have been applicable. Only 14.98 per cent indicated this to be the case once or several times. These numbers suggest that (potential) student radicalisation indicating action under the Prevent Duty is a rare event in lecturers’ professional practice. Moreover, many lecturers appear to be only superficially aware of what concretely they are expected to do under the Prevent Duty.

In order to nevertheless gain a robust picture of potential compliance with the Prevent Duty, we also presented the lecturers with a fictitious scenario that, according to the rules, clearly represents a case that needs to be reported, as follows:

“You are having a conversation with a student of yours. The student tells you they have been browsing on a website of a group that is known for its approval of the use of violence or of illegal means, which it sees as unavoidable for changing the existing societal order. The student expresses sympathy with the philosophy of the group and the readings promoted on that website, and speaks about the need to get involved in the cause.”

For various subgroups we then specified either the nature of the threat (right-wing extremism or Islamism) and the closeness of the mentoring relationship.

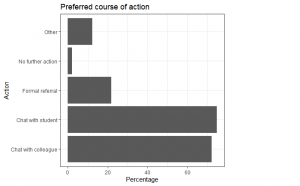

Figure 1: preferred course of action after being exposed to fictitious student contact scenario (multiple answers possible; N=809)

After being presented with this scenario, the majority (78.86 per cent) find the student’s behavior somewhat or very concerning both to their own safety and that of others. Nevertheless, less than half (33.37 percent) consider themselves likely to report the student under the Prevent Duty. As Figure 1 shows, only about 21.76 percent would formally refer the student. Instead, lecturers’ preferred options are to seek advice from colleagues (72.18 percent) or, mainly, to speak to the student privately (74.78 percent). There appear to be significant barriers to an effective implementation of the Prevent Duty at UK universities.

What role for the Prevent Duty in lecturers’ daily work?

Most of the lecturers we surveyed do not see the implementation of the Prevent Duty as a major priority in their daily work (89.74 percent). Instead they prioritize defending academic freedom, delivering high-quality education (91.58 percent), as well as ensuring and delivering equal treatment, opportunity and mentoring to students (93.69 percent). Our survey makes it very clear that lecturers consider these (and to a much lesser degree, contributing towards the University’s ability to compete for students and provide good value for money), to be the essential elements of their daily work. At the same time, the lecturers fear that the Prevent Duty might potentially cause them to compromise on their standards of educating students and defending academic freedom (53.29 percent), providing equal treatment, mentoring and pastoral care to students (55.40 percent).

In contrast, most lecturers agree that being able to act in accordance with their own values, ideological principles and political convictions is a major priority in their daily work. About half of them (45.45 percent) perceive that having to apply the Prevent Duty may cause them to compromise on their political and ideological principles and values. Accordingly, only a relatively small fraction of the surveyed lecturers (17.56 percent) report to be willing to put efforts into implementing the Prevent Duty to achieve its goals. The Prevent Duty, in other words, faces a severe acceptance problem at the frontline.

These results illuminate that even if the training can and should be improved, getting UK lecturers to police and report their own students might be a very difficult or even impossible task. It appears that many lecturers perceive the Prevent Duty to stand at odds with core values and tasks of their own profession. Moreover, the politically sensitive nature of the prevent duty might pose serious obstacle for its implementation. Given that their work requires lecturers to build a relationship of trust with students and defend academic freedom—both of which they perceive to stand at odds with the Prevent Duty—, this implementation gap is unlikely to disappear. Handing over a core state task such as antiterrorism policy to societal actors without considering the compatibility with their existing responsibilities is unlikely to be an effective approach to preventing student radicalisation.