Posted by Site Admin

28 June 2019Dr Florian Stoeckel, Lecturer in Politics, University of Exeter

In this new project, we measure the prevalence of conspiratorial thinking in Europe. We also seek to better understand the reasons why citizens believe in conspiracy theories. Joelle Tasker (Exeter BSc student graduating July 2019) and I conduct this analysis based on a novel large-N public opinion survey. The survey was conducted by Kantar Public online. It includes data on conspiratorial thinking in a diverse set of ten European Union (EU) member states and a representative set of about 1100 respondents per country.[1]

Conspiracy theories are usually country specific: for instance, a prominent conspiracy theory in the US is that the September 11 attacks in 2001 were an “inside job” by the US government. A popular conspiracy theory in Poland is about a plane crash in which Lech Kaczyński died. He was president of Poland at the time. One of the conspiracy theories about the crash describes it as an orchestrated assassination. The official investigation identifies errors of the pilots in bad weather as reason for the accident. In our project, we want to make comparisons across countries. Therefore, we use measures that gauge the extent to which citizens believe in political conspiracies more generally, rather than the extent to which they believe a country specific conspiracy theory.

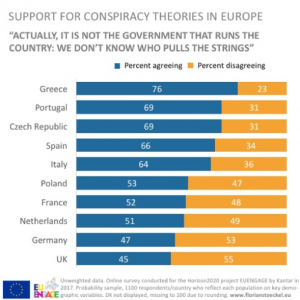

One of our measures for conspiratorial thinking is the extent to which respondents agree with the following statement: “Actually, it is not the government that runs the country: we don’t know who pulls the strings”. We use an individual’s agreement with the statement as one indicator for the presence of conspiratorial thinking. Our preliminary findings reveal much variation between the ten countries in our sample: agreement with this statement ranges from 45 percent in the UK to 76 percent in Greece.

We are also interested in the factors that make it more or less likely for individuals to believe conspiracy theories. Based on a rich literature that examines conspiratorial thinking in the US (e.g. Uscinski and Parent, 2014; Oliver and Wood 2014, Goertzel, 1994), we expect three factors in particular to help us understand who exhibits conspiratorial thinking in Europe. This includes the level of control that individuals perceive to have over their lives, predispositions, and situational triggers. When citizens experience little control over their own lives, they are also more likely to assume that they cannot affect politics either. A conspiracy theory offers a way to rationalise this attitude: it is impossible to affect politics because “we don’t know who pulls the strings” anyway. Experiencing little control over one’s life can be a result of limited material resources, e.g. having a lower income or being involuntarily unemployed. Education, on the other hand, is a cognitive resource which can make it easier for individuals not to feel lost or powerless in a complex political world.

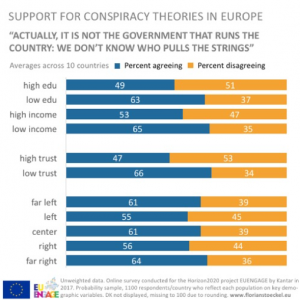

Our survey data support the important role of material circumstances and cognitive resources. On average, the share of respondents who exhibit conspiratorial thinking measured with the above-mentioned survey item is 65 percent among respondents with lower incomes[2] and it is 53 percent among those with higher incomes. The pattern is similar when it comes to cognitive resources. The share of respondents who show conspiratorial thinking among those who did not attend university is 63 percent, but it is only 49 percent among those with the highest levels of education in our sample.

The literature highlights the important role of predispositions for conspiratorial thinking (e.g. Goertzel, 1994; Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig, and Gregory, 1999). We focus on two predispositions: trust and ideological orientations. We are interested in trust as the perception of the world as either a place where one can generally trust other people or a place where one should rather not trust other people. Voters might apply this conception of the world to the realm of politics: citizens who see the world as a place where one can trust other people might be less inclined to think that actors who are unknown to the public are “pulling the strings.” Our preliminary results support this notion. Among individuals who tend not to

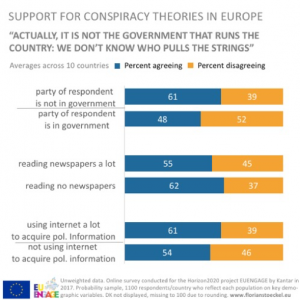

An argument from the US context is that conspiratorial thinking is not only a result of characteristics of an individual but that it is also driven by contextual factors. For instance, it makes a difference for voters whether the party they support is in government (Uscinski and Parent, 2014). Voters are less likely to believe in covert agency when their own party is running the country. We find support for this dynamic also in Europe. The share of individuals who say that “we don’t know who pulls the strings” is 48 percent among those whose own party was in government at the time of the survey. The share of respondents who agree with this statement is 61 percent among those respondents whose party was not in government.

Finally, media consumption can be related to the extent to which respondents believe conspiracy theories. We analyse the role of newspaper consumption and news consumption online. We find stark differences: individuals who read newspapers a lot are much less likely to engage in conspiratorial thinking than those who do not read newspapers at all. In contrast, individuals who get their news frequently from online sources are more likely to engage in conspiratorial thinking than those who do not rely on the internet for political news.

trust other people, 66 percent agree with the statement “that it is not the government that runs the country: we don’t know who pulls the strings”. Among respondents who tend to trust other people, the share of individuals who agree with the statement is only 47 percent.

We also examine if left-right ideology is related to conspiratorial thinking, which is an issue that is being discussed vividly in the research literature (e.g. Uscinski and Parent, 2014; van Prooijen, Krouwel, and Pollet, 2015). Our measure for left-right ideology in this analysis is a general left-right self-placement question which does not differentiate between economic issues and cultural issues. We find that the share of individuals who engage in conspiratorial thinking is lowest among those who take a moderate left leaning position or a moderate right leaning position. Conspiratorial thinking is more widespread among individuals who locate themselves at the centre of the left-right dimension, among those with extreme left leaning positions, and it is most prevalent among individuals with extreme right leaning positions.

In sum, we find that conspiratorial thinking is widespread in Europe. The factors that have been identified in an American context also matter in Europe: resources, predispositions, and situational triggers help us to understand the differences between citizens who show conspiratorial thinking and those who do not show conspiratorial thinking. The next step of our analysis includes the development of a more fine-grained instrument to measure conspiratorial thinking and a multivariate analysis of the correlates of conspiratorial thinking.

[1] A household income of 30.000 Euros or less before taxes.

[2] One of the few other comprehensive surveys with a focus on Europe was conducted as part of the project CRASSH at the University of Cambridge. Results can be found here.