World Seagrass Day

Cornwall: A Stronghold for Seagrass in the UK

Seagrass ecosystems are vitally important marine habitats. They store carbon, improve water quality and are hotspots for marine biodiversity. This #WorldSeagrassDay we talk to Dr Chris Laing from the University of Exeter, Centre for Ecology and Conservation about his work on seagrass beds in Cornwall. Read on for more:

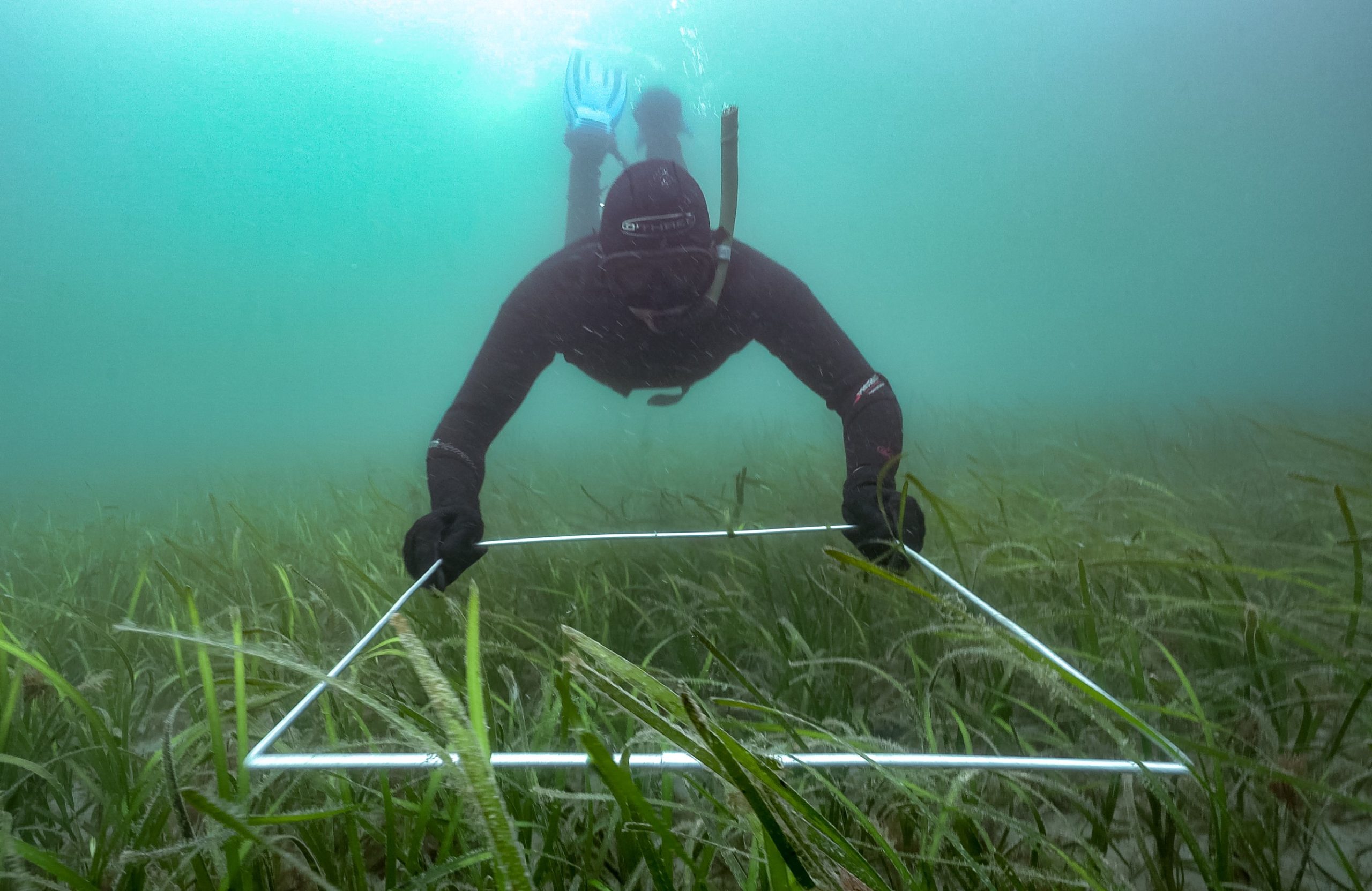

Dr Chris Laing laying a transect in the Helford Estuary. Photo Credit: Lewis M Jefferies.

How much seagrass do we have around Cornwall?

With the discovery of the seagrass beds in St Austell Bay and Mount’s Bay it is now clear that Cornwall is a stronghold for seagrass in the UK. The West Coast of Scotland is probably the only other place that has as much as we do down here, with the caveat to that being that you don’t really find seagrass until you look for it and it so happens we have been looking for it quite a lot. But everyone is excited, as on paper we’ve got a large amount and it seems to be in very good condition. Our project in 2021 mapped 170 hectares in the Fal and Helford SAC alone and since then two other beds have been mapped – 200+ hectares in Mount’s Bay and 350 hectares in St Austell. In the Fal and Helford SAC in particular, seagrass represents a large proportion of the habitat.

Snakelocks anemone on seagrass, Cornwall UK. Photo credit: Lewis M Jefferies.

Why is Cornwall a stronghold for seagrass?

Nationally, nutrient levels in seagrass have been identified as one reason the habitats are in decline and in general, the water quality around here is good, which is probably why we’ve got so much. Our analyses of seagrass plants here tell us that nitrogen levels are similar to those in the Isles of Scilly. We have been comparing these numbers through a project which ran last summer. Seagrass is however only found on the south coast. The north coast doesn’t have the right sediment and is too exposed generally. Estuarine conditions and the bays in the south coast are well suited to seagrass.

Seagrass bed in Mount’s Bay, Cornwall. Photo Credit: Lewis M Jefferies.

What research have you been carrying out on Cornwall’s seagrass beds?

I have been working on seagrass beds for about 6 years now locally. Initially it started with research students who wanted to do a project on how water quality might effect seagrass health in two different locations. They got some really interesting results and so I continued that work and started to think about seagrass more from a research perspective. My background is in carbon cycling and my PhD was in biogeochemistry and so I studied carbon cycling in those environments.

Quite a lot of the literature in the last two years has been focused on the role of seagrass in blue carbon storage and their importance globally. I was keen to get involved in that work locally. We know that we have seagrass beds in Cornwall but they are quite different to tropical seagrass beds, and so their role in terms of blue carbon might also be quite different. I was approached by the Council to do a blue carbon assessment for their Cornwall Habitat Bank project, where they are valuing ecosystems in a number of ways. One of these ways is through carbon capture because they want to achieve net zero by 2030. Therefore, they commissioned me to do some work on the carbon budget of the seagrass beds here in the Fal and Helford SAC (Special Areas of Conservation) in 2021.

I have been working with local groups like the Wildlife Trusts and Cornwall Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA), who have done some of the habitat mapping for me and published that report for the Council last year. This has led to a number of contacts and work with people like Natural England, the Environment Agency and the MMO who are all interested in understanding natural capital, which places some emphasis on blue carbon as well as biodiversity stocks. I think everyone is understanding that we will struggle to meet our 2030 commitments without some form of offsetting. We’re looking to marine habitats now to see whether they can offer some of that offsetting.

Seagrass bed in Cornwall, UK. Photo credit Lewis M Jefferies.

Can Cornwall’s seagrass beds offer much as carbon stores?

To me the picture is quite mixed really. The seagrass beds do seem to be valuable carbon stores but possibly not as valuable as other marine ecosystems, which is something I have started to look at now, expanding our focus to mearl, kelp and saltmarsh. However, the quantification of seagrass from a carbon perspective might not actually be the most important thing. We’re now talking about valuing the other ecosystem services those habitats offer. We know from the literature that many commercial fish species spend their juvenile stages sheltering in seagrass beds and so the value of the habitat is extensive simply because of that. There are also general biodiversity benefits to having the three-dimensional structure of seagrass available to juvenile species. For example, it is one of the few environments you’re likely to find seahorses in, because they seek the protection of the beds. Cuttlefish, nursehounds and other animals are attracted to the meadows to lay their eggs or shelter there.

We’ve also got the ocean health benefits. One of them is obviously cleaning the water – there is evidence that seagrass in close proximity to coral reefs performs a really important antimicrobial function. I don’t look at this particularly, but I am looking at the seagrass holistically from the creatures that live in the sediment to the creatures that live on or in the seagrass.

Pollock in seagrass meadow, Cornwall UK. Photo Credit: Lewis M Jefferies.

What other seagrass research is being undertaken in Cornwall?

We’re using baited remote underwater video cameras with other teams from the university, like Kristian Metcalfe and Owen Exeter, to try and catalogue the kind of species you might find in seagrass and quantify that ecosystem service. How many species are of commercial value and are they as biodiverse as the literature makes them out to be? If they are performing that function, it’s interesting to know which species are benefiting the most.

My work also intersects with various harbour authorities – I’ve been working with Falmouth Harbour Authority who are proactive with protecting seagrass habitats within the water they have jurisdiction over. From Flushing to St Mawes bank they’ve been doing some cool stuff, like trialling restoration and prototypes for breaking down seagrass seeds in natural environments, in a floating buoy. We are also working together with the Wildlife Trusts on how water quality might affect the seagrass, looking forward and moving away from carbon slightly. If we think about these habitats persisting and expanding over time which is what we want, the best way to do that is to improve water quality and the 2nd way to do that might be to restore these beds.

On the water quality front, I’m working with Falmouth Harbour Authority to install a turbidity measurement system in Flushing to try and link sewage outflow to declines in water quality. There’s a well-known problem in the Fal and Helford with storm sewage overflow which is above the number of legislated releases every single year. It’s a big problem I think for the seagrass. In a threat assessment I did I classed it as probably the greatest threat to the persistence of seagrass here in the Fal and Helford. It definitely needs to be studied, but the Environment Agency data on water quality isn’t high enough resolution or consistently measured enough to actually give us that data. We’re going to try and measure it ourselves and link it to seagrass health.

In terms of restoration, we are now working with the Council on a NEIRF project (Natural Environment Investment Readiness Fund) that will start in the coming months. I’ll be working with Regan Early to understand more about the carbon budget of Mounts Bay, as that’s the 2nd largest seagrass bed in Cornwall behind St Austell. We’ll be working with the Ocean Conservation Trust on that one as well. Regan will use some habitat mapping approaches which we applied to a ReMEDIES project in 2019 to identify where suitable habitat might exist to restore those beds and increase the size of them. The general approach to seagrass restoration is to pick a seagrass bed with lots of other suitable habitat around it and try to expand the extent of that existing bed because you’ve got a lot more chance of success. This makes the focus protecting and expanding what we have. That project will start soon and run until the end of the year.

Seahare on seagrass, Cornwall UK. Photo Credit: Lewis M Jefferies

Are local communities aware of the importance of these habitats?

Communities in the Fal and Helford SAC areas are proactive and engaged in sharing public information on seagrass and its value and protection. There are now a few no anchor zones to protect the seagrass, and the Ocean Conservation Trust are planning to add identification buoys to demarcate the seagrass bed in Mounts Bay to make recreational boat users aware of it, which we are supporting.

If you would like to learn more about seagrass in Cornwall take a look at:

- This Cornwall Council Article: Hidden underwater world: huge seagrass bed discovered in Cornwall could help tackle climate change – Cornwall Council

- Work from Cornwall Wildlife Trust: Restoring Cornwall’s Seagrass | Cornwall Wildlife Trust

The fantastic photos used in this article were kindly provided by Lewis Jefferies. Instagram: lewismjefferies.camera