Written by Tara Williams and Dr Ben Harris

A red sun sets over sapphire Mediterranean water, bringing the One Ocean Science Congress conference to a close and beckoning forth the United Nations Ocean Conference. The hazy amber light, caused by smoke from distant Canadian wildfires, casts the city of Nice in a sense of urgency. As scientists, conservationists, policymakers, and ocean activists gather to strategize for the second half of the UN Ocean Decade, they do so beneath a vivid, inescapable reminder of the far-reaching threads that bind our climate systems together.

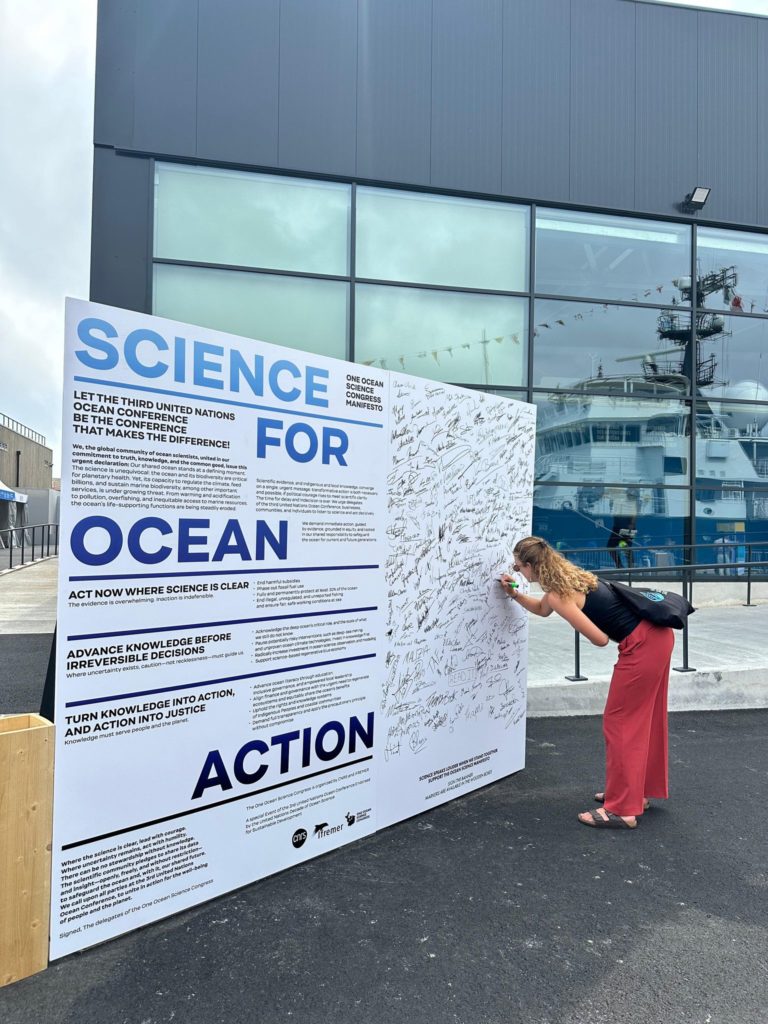

We recently returned from back-to-back conferences in the south of France. During the first week of June, over 2000 scientists convened at the One Ocean Science Congress (OOSC), the scientific pre-runner to the world’s third UN Ocean Conference (UNOC3). Almost every facet of marine conservation science was represented, from cetacean bioacoustics and marine anthropophony, through calls from Takashi Gojobori for “more big, big, huge data”, to ocean law and indigenous socio-ecosystems. We attended with colleagues from the Convex Seascape Survey, a 5-year multidisciplinary project seeking to understand the carbon locked away in soft marine sediments and its vulnerability to human disturbance. Our contributions included four scientific posters, a talk on the historic global extent of bottom trawling by Dr Ciarán McLaverty, and numerous discussions featuring our Principal Investigator, Professor Callum Roberts. Energy for change was palpable; following the premier of David Attenborough’s Ocean, the announcement by Environment Secretary, Steve Reed, to ban bottom-trawling across 41 marine protected areas (MPAs) in the UK, and a new Nature commentary on protecting the high seas from all exploitation forever, we couldn’t have been there at a better time.

Over the course of 5 days, through 500 oral presentations and 620 posters, ‘the science we need for the ocean we want’1 was presented in every shape and size. The jargon flowed; blue carbon, blue economies and blue justice were hot topics, whilst mCDR technology2 and the BBNJ Agreement3 promised solutions to 30×304 and SDG 145. The aim of OOSC was to package science into bitesize and actionable chunks to be chewed, digested and infused into government policy discussions during UNOC the week after.

During the weekend break between OOSC and UNOC, police presence appeared to triple; scientific posters were quietly removed; new, public-facing exhibitions were erected, and what had been a space for collaborative conversation on ground-breaking marine conservation science became the tightly controlled ‘Blue Zone’, open only to heads-of-state and ‘ocean officials’ with the correct QR code hanging from their necks in an ocean-friendly cardboard lanyard. We still had access to the ‘Green Zone’ within Nice’s Palais des Expositions, the setting of a Round 2 of more publicly accessible scientific panels, stalls, stands and immersive experiences.

The Green Zone was a veritable coral reef of activity and noise and clashing side-events. There was a broad mix of representatives from purist scientific institutions to almost every ocean-facing corporate group one can think of, seeking to have their branding splashed across the right side of history: OceanX, MBARI, Schmidt Ocean Institute, Scripps, The Bloomberg Ocean Initiative, Digital Ocean, Copernicus Marine Service, Tara Ocean, Sea Beyond, The Nature Conservancy, Mission Blue, Under the Pole. Laurent Ballesta‘s stunning underwater photography exhibition adorned the walls, whilst futuristic, digital eco-art from Yacine Ait Kaci and Virtual Reality from Institut Oceanographique Paul Ricard embodied hope for pristine oceans on Planet Earth once again. Emelia Arthur, the Minister for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Ghana, and Mere Takoko, the co-founder of Pacific Whale Fund, were voices of clarity and intention generating real change through legal frameworks, rising out of a sea of excitement, #GRWMs, and Sylvia Earle selfies.

Meanwhile, we’re promised Ocean Decade progress was being applauded, and new commitments were being agreed in the Blue Zone. French Polynesia announced the creation of the largest MPA in the world, of nearly 5 million square kilometres, over a fifth of which will be highly or fully protected. Chile has expanded the Juan Fernández MPA, bringing the country’s EEZ protection to over 50% and placing it among the global leaders in ocean conservation, fitting for the newly revealed co-host of UNOC46. And closer to home, the UK’s proposal to ban bottom trawling within our MPAs will focus on ecologically sensitive and vulnerable seabed habitats, covering 30,000 km2 of national waters. The world inches forward.

Towards the end of the conference, we heard rumblings throughout the Green Zone; what happens when we go home? How do we keep this energy going, and how do we fill the gaps that remain? Whilst 50 countries have ratified the BBNJ Agreement, 10 more signatures are needed to even begin enforcing the High Seas Treaty. A precautionary moratorium on deep sea mining has been supported by 37 global leaders, sending a clear message that the deep sea needs to be protected, but without endorsement from the US, Russia, China and confirmed UNOC4 host South Korea, this carries little weight. Moreover, a moratorium is, by definition, temporary. Even this year’s host, France, has struggled to discipline its domestic fishing industry which trawls the seabed in 98% of the country’s MPAs. The science is clear. It’s now up to policymakers, delegates, businesses, communities and individuals to seize the moment and fulfil the official call by OOSC to “end harmful subsidies, phase out fossil fuel use, protect at least 30% of the ocean, and end illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing”.

The closing of UNOC3 calls half time on the UN Ocean Decade. Whether the recent action-packed weeks will lead to actionable solutions in the run up to 2030 remains to be seen. However, while the US refuses to participate and the name Trump appears to be a faux pas caught in the throats of environmental scientists around the world, naivety and hope seem difficult to differentiate. Amidst news that our largest terrestrial biome is ablaze, intercepted aid boats, and on-going domestic and international conflicts around the world, one point is clear: the ocean is not what separates us but what connects us.

Tara Williams and Ben Harris are researchers at the University of Exeter, working as part of the Convex Seascape Survey.

- The campaign tagline of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021 – 2030). ↩︎

- mCDR refers to marine carbon dioxide reduction, an emergent approach that manipulates the ocean’s ability to capture atmospheric CO2. These technologies range from nature-based solutions like seaweed planting to those on the frontlines of technological advancement, like ocean alkalinity enhancement. ↩︎

- Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) is the formal name of the High Seas / Global Ocean Treaty. ↩︎

- The 30 by 30 targets are principal among the goals promised to come into force by 2030 and refer to the protection of 30% of land and ocean to halt biodiversity loss and the adverse effects of climate change. ↩︎

- SDG-14 – or UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 – is ‘Life Below Water’, dedicated to ocean conservation. It is the least funded of all the SDGs. ↩︎

- UNOC4 is confirmed for 2028. It is set to take place in South Korea, and be co-hosted by Chile. ↩︎