Cryo-electron and Fluorescence Microscopy Unravel the Mechanism Behind OtV5 Viral Infection in Ostreococcus tauri

Written by Keith Harrison and John Duffy, PhD researchers in Complex Living Systems

The Hidden Battlefield Beneath the Waves

At this very moment an invisible war is raging in our seas. Every second, roughly one sextillion viral infections occur in marine waters worldwide. The combatants are viruses attacking marine phytoplankton, organisms barely visible under the most powerful microscopes.

Our focal point is Ostreococcus tauri, a microscopic green alga measuring just 800 nanometres across and the smallest free-living eukaryotic organism known on Earth. Despite their diminutive size, these photosynthesisers capture atmospheric carbon dioxide and form the base of oceanic food webs. When viruses attack them, the implications ripple through the entire global climate system. Our research asks a fundamental question: how does infection occur between the alga O. tauri and its virus Ostreococcus tauri virus 5 (OtV5)?

Why Tiny Infections Have Massive Consequences

Marine phytoplankton are major players in the Earth’s carbon cycle, capturing roughly half of all atmospheric CO₂ through photosynthesis. When viruses kill these organisms, much of this carbon sinks to the ocean floor, effectively removing it from the atmosphere for centuries. This biological carbon pump, known as the carbon shunt, represents one of nature’s most important climate regulation mechanisms.

Viruses fundamentally alter the fate of these algae. They infect and destroy immeasurable numbers of phytoplankton cells daily, and when infected cells burst open, they spill carbon-rich contents into surrounding water. Will this organic carbon sink to the depths? Be recycled by bacteria? Return to the atmosphere as CO₂?

The Smallest Battlefield: OtV5 and Its Host

Ostreococcus tauri represents an extreme case of cellular miniaturization. This single-celled eukaryote packs a nucleus, chloroplast, and mitochondrion into a space smaller than many bacteria, yet it remains fully independent and capable of capturing carbon from the atmosphere. Found worldwide in coastal waters, these algae are crucial carbon capturers that support entire marine ecosystems.

Its predator, OtV5, is even smaller at 120–180 nanometres. This virus attaches to the cell membrane, injects its genetic material, hijacks cellular machinery to manufacture hundreds of copies, and eventually bursts the cell apart, releasing viral offspring. Understanding this model provides insights applicable to countless other virus-host systems throughout the oceans.

Seeing the Invisible: Our Scientific Arsenal

Studying objects invisible to standard microscopes requires specialised tools. We employed transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which uses electron beams rather than light to reveal details 1,000 times smaller than optical microscopy, allowing visualization down to the nanometre scale where individual viruses become visible.

Though TEM has existed for nearly a century, applying these structural bioimaging techniques to marine systems represents genuine innovation. While virologists routinely use these methods to study bacteriophages or human viruses, marine virus research has historically lagged. Our work helps bridge this critical gap.

Visualising the Viral Architecture

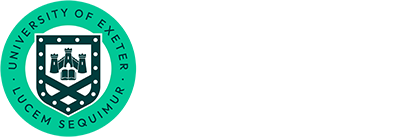

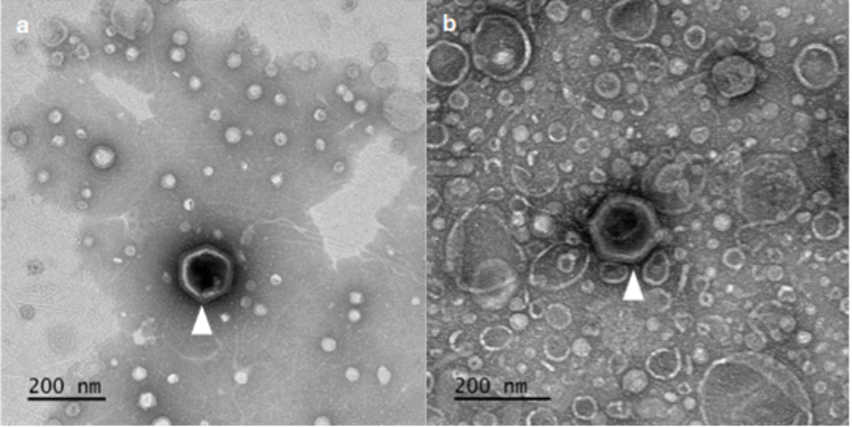

Our electron microscopy revealed fascinating details about OtV5 structure and infection. We observed the compact nature of OtV5 infection with newly synthesised capsids within infected O. tauri cells. Images showed four spherical cells approximately 800 nanometers in diameter, each with clear internal structures including chloroplasts, nuclei, and mitochondria. Small circles approximately 120 nanometers in diameter—individual virions—were visible inside two of these cells.

Magnified OtV5 capsids displayed icosahedral structure with varying degrees of angularity. Remarkably, one appeared enveloped by an unusual membrane-like structure, suggesting distinct viral assembly stages. The angular capsid structures reveal protein shells protecting viral genetic material. Understanding their atomic architecture illuminates potential mechanisms of attachment to host cells and quantifies how much carbon is locked in each virus particle. With billions of these particles floating in ocean water, viral capsids represent a significant yet previously unmeasured carbon pool.

Structural Insights and Their Significance

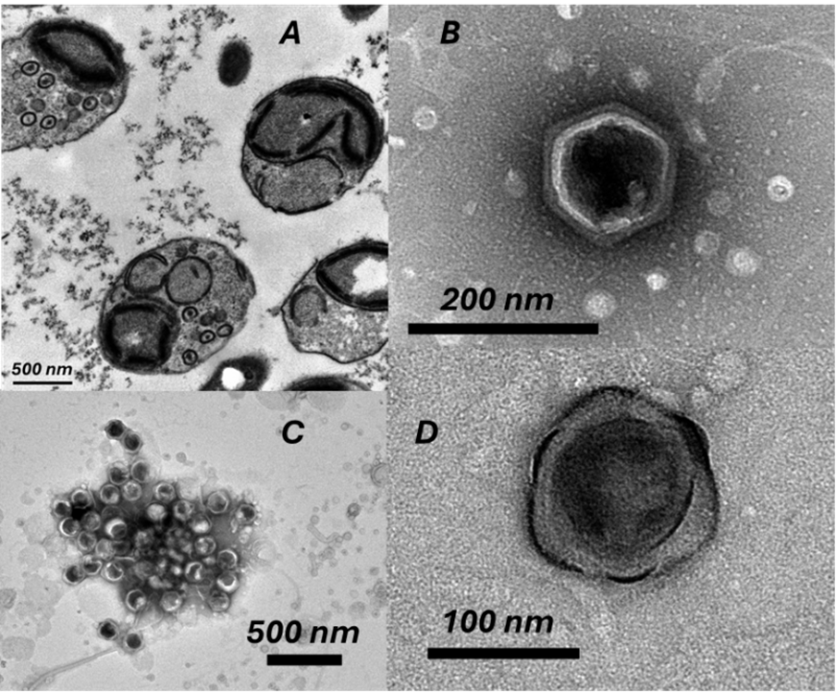

These structural observations reveal multiple aspects of the viral infection process. Empty and filled viral capsids suggest that virus assembly and DNA packaging occur as separate processes, providing critical clues about infection mechanics. A important consideration is how much cellular metabolism is redirected toward synthesising empty capsids. The distinct aggregation patterns between susceptible and resistant cultures of O. tauri indicate that viral infection triggers cellular responses that alter cell surfaces.

Remarkably, only one other strictly marine virus of the family Phycodnaviridae has been studied at a high-resolution structural level: EhV201. Our work has taken steps towards optimising the purification and sample preparation techniques necessary for collecting a high-resolution data set for OtV5 infection. Ostreococcus is far more closely related to the plants we commonly find in the garden centre than to the haptophyte Gephyrocapsa huxleyi that EhV201 infects, making our findings particularly valuable. We now possess quantitative structural data on viruses infecting distantly related algae, substantially expanding the comparative framework for understanding the biology of viruses infecting diverse host lineages that both represent key contributors toward ocean health.

Resistance Revealed: A Population-Level View

Our research provided crucial insights into how O. tauri responds to viral infection. Comparing susceptible and resistant cultures through electron microscopy revealed striking differences. The susceptible culture showed cells averaging approximately 1 µm² in cell area with more extracellular connections, while the resistant culture displayed cells averaging around 2 µm² with reduced extracellular connectivity.

Resistant strains have larger cell sizes, potentially as a defence mechanism against viral infection. This cellular-level adaptation reveals how O. tauri populations respond evolutionarily to viral pressure; a finding with significant implications for understanding population dynamics and viral-induced selection in marine ecosystems, as well as carbon capture within these now larger organisms.

Collaborative Breakthroughs on Limited Funding

The £2,000 grant from Exeter Marine enabled two PhD students to access specialized equipment including the ZEISS Elyra 7 Lattice SIM, ZEISS Axio Vert.A1, and JEOL JEM 1400 Transmission Electron Microscope, along with hands-on training from expert operators. We also acquired essential consumables—fluorescent dyes for DNA staining, reagents for concentrating viruses, and specialized materials for TEM visualization.

Marine virus research remains severely understudied in the UK despite viruses being the most abundant biological entities in the ocean. Your support enabled early-career researchers to focus on developing robust methods for understanding virus-algae interactions fundamental to ocean health and global carbon cycling.

The Next Wave: Broader Applications

We have successfully taken steps towards characterising the OtV5 virion. Future work will continue the development of our approach and ultimately be applied to other virus-host systems, building comprehensive datasets of empirical data that could be used for climate models. We’re particularly interested in how novel metabolic functions encoded by viruses change the metabolic profiles of their hosts; changes that have major effects on biogeochemical cycling when multiplied across billions of infections occurring each second.

Understanding the Climate Regulators

These invisible entities deserve recognition as climate regulators of the first order. Viruses are not always destructive; they’re essential regulators maintaining fine balance within microbial communities and driving nutrient recycling. Every day, viral infections influence how much atmospheric CO₂ gets sequestered to the deep ocean, how efficiently energy flows through the marine food web, and ultimately, how our planet’s climate functions.

The ocean contains approximately 10³¹ viruses, far outnumbering all other biological entities on Earth. Yet we’ve barely begun understanding them. As the world grapples with climate change and ocean health, our attention to these invisible warriors in the ocean’s hidden war becomes increasingly urgent. They might hold the key to understanding our planet’s future.

We’re very grateful to the Exeter Marine Fund for supporting our research and the invaluable expertise provided by the Bioimaging Centre at the University of Exeter.

The Exeter Marine Fund has been designed to respond to the most urgent threats by bringing together small gifts to have a big impact when and where funding is needed. The Fund enables us to continue to play a crucial role in monitoring and protecting our marine ecosystems and shape positive change in practice, policy and innovation, and has successfully funded a number of student research projects over the last few years.

If you’d like to talk to us about supporting a particular area of marine research, please email alumni@exeter.ac.uk or call +44 (0)1392 723141.