Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Helen Vassallo

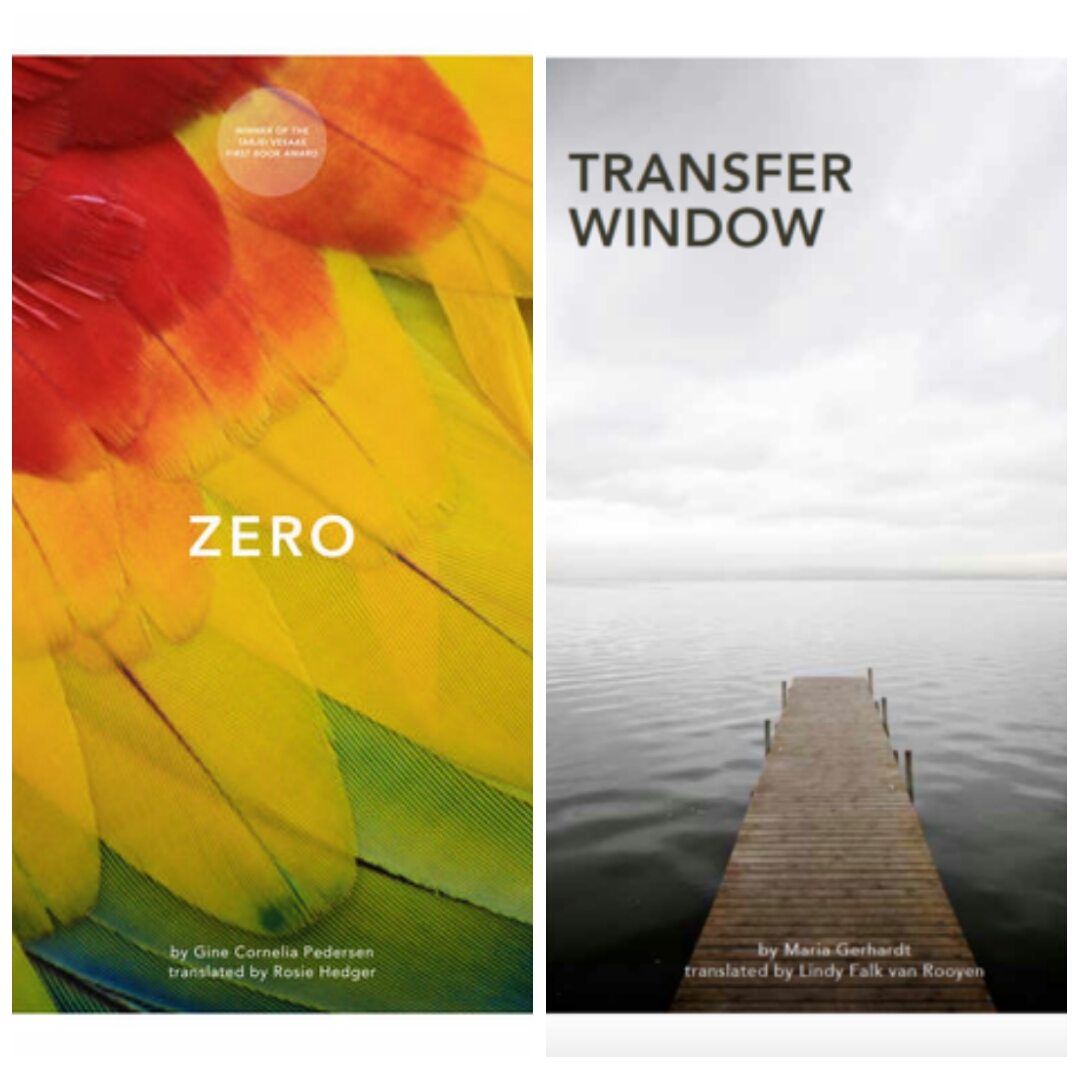

2 July 2019Nordisk Books is an independent publishing house founded in the UK in 2016, with a focus on modern and contemporary Scandinavian literature. I was fortunate to read two of their recent releases, and am bringing them to you today in a special double-bill review.

Zero is the stream-of-consciousness narrative of author Gine Cornelia Pedersen’s deteriorating mental health, transitioning from a childhood in which she “absorb[s] everything unfiltered” to an adult life in which:

“I don’t want help

I like it at rock bottom

I’m drowning in my own ego

It feels glorious”

Described on the cover as a “punk rock single of a novel”, Zero certainly bears characteristics of punk rock: fast-paced, hard-edged and stripped bare, this is a painful book, but also an immensely lyrical one: it pulses with obsessive intensity, bursts with life and sound and vivid descriptions. The layout of the text looks something like poetry; thoughts (and pages) are incomplete, and yet the narrative always seems carefully structured, even when sentences are cut adrift and grammar goes out of the window. There are no full stops – or, rather, there are a couple when doctors speak, but none in the monologue – indicating the outpouring and intensity and the lack of definitive “endings” (indeed, the ending itself was the only part I struggled to understand, as it seemed almost hallucinatory – whether from the effects of medication or imagination I don’t know). The story is deeply personal, and the subject pronoun “I” is used repeatedly throughout Zero, yet although such liberal repetition of “I” has the potential to become rather self-indulgent, and indeed such an intense book could easily be quite bleak or emotionally draining, neither of these is the case. On the contrary, this is an absorbing, throbbing narrative, a compelling and compulsive read.

Rosie Hedger’s translation is faultless: she has captured the voice of a tormented millennial perfectly, and every word of this spare, gut-punching book is perfection. One of the questions I found most interesting was about where the real “sickness” lies – is it with a woman struggling with her mental health, or with the way in which society deals with her? Forced into a psychiatric hospital, the narrator is injected with tranquillisers, given pills that make her a stranger to herself, and repeatedly told that this is essential (not even watered down with a platitude of it being “for her own good” – indeed, we rather suspect that the confinement is not for her own good at all). She begins her own internal revolution:

“I realise these people are sicker than I ever expected

That I’m going to have to inwardly oppose them”

This “inward opposition” is carried out by controlling her behaviour in order to assure her release (“I open my mouth to say something but I realise that it’s better to keep my thoughts to myself here”). She clings to these thoughts, to the hope that they will return, to a time when she will feel as though she inhabits her own body again. And when this begins to happen, it also symbolises a return to life:

“The feeling has started to return to my body

I’ve started thinking again

Constantly thinking

Thoughts sweep through me

It’s as if I’m getting high

Getting high off the sun, off the night, off people on the street”

It is not the medical staff with their needles and prescriptions and neat labels of psychosis who save the narrator in the end, but – if indeed she is “saved” at all, for we leave her only part-way towards a recovery that might only ever be temporary – it is by her own determination and her awareness of her mother’s love pulling her back towards life:

“And that’s when it hits me

The love in Mum’s voice

The tenderness

As if she were talking to something that might break if she were to say the wrong thing

Her absolute, total, unconditional acceptance of me”

This tribute to the mother is not at all clichéd – it is not that “love conquers all”, but rather a moving eulogy to an unconditional love that creates a lifeline where modern medicine does not. In Zero, Pedersen gives voice to all that is suppressed, to emotions dismissed as self-indulgence and treated as psychosis, and to the need to be part of the world, not isolated from it. This urgent, rebellious short text is a countdown to zero, a ticking clock, a timebomb, and a gem waiting to be discovered; I highly recommend it.

In the latest release from Nordisk Books we move from mental illness to physical illness, as Transfer Window is inspired by author and musician Maria Gerhardt’s terminal cancer diagnosis. Gerhardt died in 2017 at the age of 39, and in this book she relates the difficulties of knowing that life will be cut short, and the impossibility of an old age that she can only imagine. Transfer Window is also an indictment of the failure of “healthy” friends and members of society to provide adequate palliative support: Gerhardt’s friends want her to cheer up, remind her that she “seemed so much better” last time they saw her, and would prefer that she constructed a façade of coping with her diagnosis. The book’s subtitle (“Tales of the Mistakes of the Healthy”) indicates the detrimental effect that lack of understanding and compassion can have on an ill person and, as in Zero, calls into question where the real sickness lies.

Though there is much realism in Transfer Window, the setting is a futuristic representation of end-of-life care. The majority of the narrative takes place in a vast hospital compound, a section of the city that has been blocked off and dedicated to the dying. They leave their loved ones (“We have already said goodbye to our families in a beautiful ceremony”) and enter a white-walled hospital where “bar a miraculous recovery, once you check in, you can never leave.” This hospital for the dying also seems like a voluntary prison (“I’ve been here three hundred and eighty days”; “I etch lines in the wall, to the lift of my mattress, in order to keep track of how long I have been here”), and eventually the narrator acknowledges that “this really is a ghastly place to be.” The dystopia of a seemingly perfect “death hotel” reminded me of Ninni Holmqvist’s marvellous The Unit (translated by Marlaine Delargy for Oneworld and reviewed here) – the residents seem to have all they could want, including access to marijuana oil and to virtual reality experiences that allow them to relive their most cherished memories – but what they do not have is a future.

The inconsistency of the translation was the one thing that let this book down for me: though much of the translation conveys a stark beauty and musicality, in places some literal or calqued phrases creep in. There are also some editing errors, including a number of rather oddly placed commas – this shouldn’t spoil your appreciation of the book, but it’s a shame as this is otherwise a powerful and moving text. Where Falk van Rooyen has excelled in the translation, however, is in its lyricism: there are a number of sections which are almost unbearable in the rawness of their pain. In particular, references to the narrator’s (healthy) partner are immensely moving: “My sweetheart, you are not to see me lying here sobbing. You are not to see me hunched over the toilet bowl, howling for help down the drain.” It is not only life that is cut short, but also love (“The only thing I find frustrating about the next dimension is that you are not coming along”), and yet this is never saccharine. Rather, we are made aware that the partner gets to carry on where the narrator is cut off: when the partner shouts at their son that she doesn’t have time for his reluctance to get dressed for kindergarten, the narrator comments that “I hated that you said you didn’t have time. You have so much time. You have nothing but time.”

This was a painful book to read, particularly with the knowledge that the author had died. Such confrontation with mortality is rarely comfortable, but I rather think that’s Gerhardt’s point: she doesn’t want to make things comfortable for her reader, she wants to share her pain. Gerhardt’s descriptions of her ravaged body (“My body knew pain which the body can’t bear”, “my body seized in the agony that only a body in absence of motion feels”, “a body forever in a state of emergency”) are just as important as her reflections on health and illness, and the most human thing we can do is to read this book without trying to find a “silver lining”, but rather learn from it to make fewer “Mistakes of the Healthy”.

Review copies of Zero and Transfer Window provided by Nordisk Books (via Inpress Books)