Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Mark

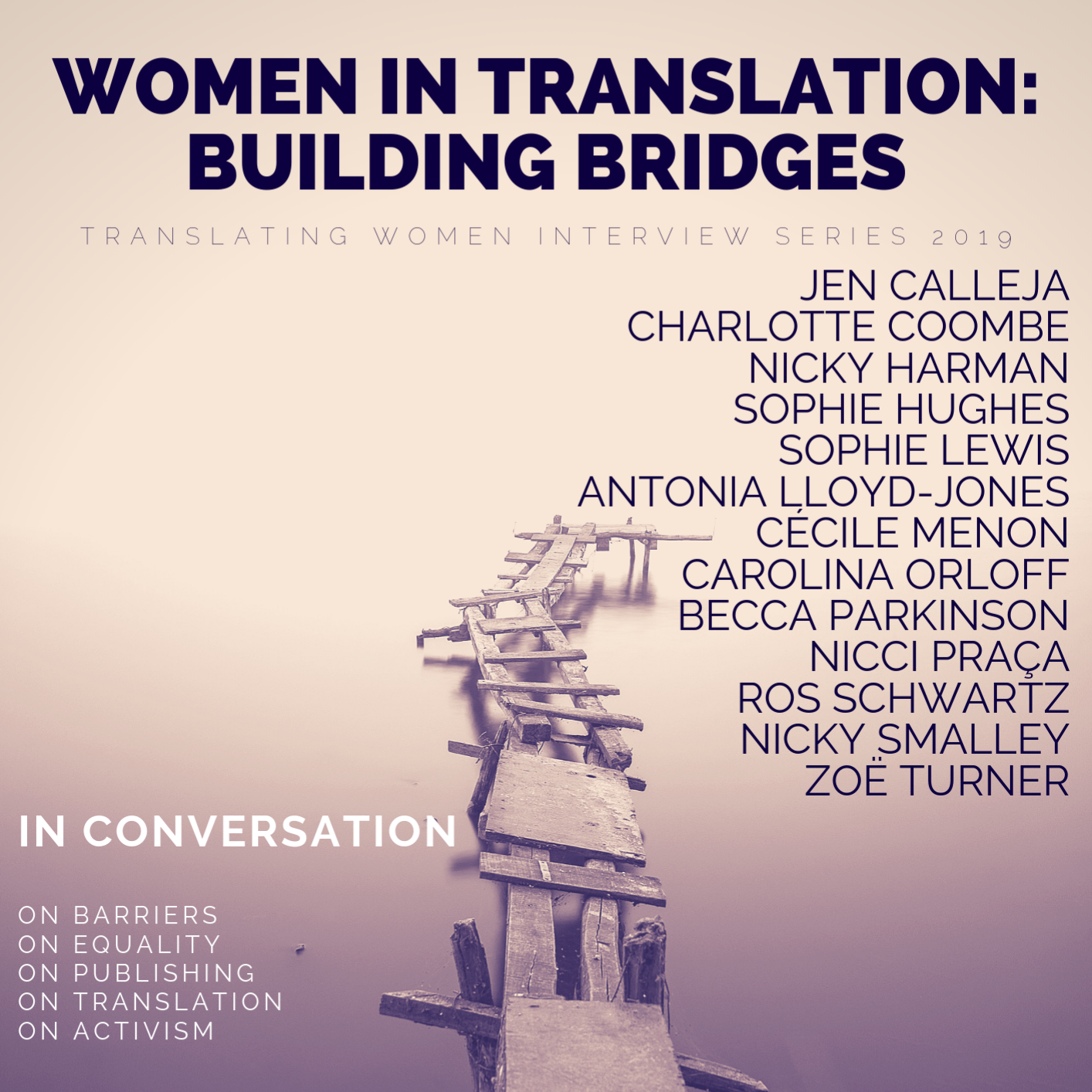

23 August 2019In the springtime this year, I published a remarkable interview with translator Sophie Hughes. Shortly after Sophie’s interview I received a small grant to travel across the UK and turn this into a series, interviewing translators, publishers and publicists to explore the barriers facing women in translation, and the ways in which these might be broken down. Later this year I’ll be publishing the rest of the interviews here, but what strikes me most as I transcribe them is how many ideas recur – explicitly or implicitly – across the many and varied responses to my questions. So I am offering this “prelude” by setting extracts from each interview in dialogue with one another: I hope you find this as fascinating as I do, and I look forward to sharing the full interviews with you in due course.

I am very grateful to all these dynamic and talented interview participants. Their goodwill, good humour and wisdom are inspiring: every single person I approached agreed to meet with me, and gave freely of their time and their thoughts; my appreciation is matched only by their generosity.

SOPHIE HUGHES: “whenever [women writers] sit at their desks to write, the blank page is the least of it; it’s when their page is full that the battle begins”

SOPHIE LEWIS: “Women do struggle to get published outside the Anglophone world; they have so many things against them. They struggle to get published, and to get published well – in big enough numbers and with a big enough marketing campaign behind them – to make an impact. So they then don’t win prizes. Everything is against them.”

BECCA PARKINSON & ZOË TURNER: “With our Reading the City anthologies, we try to find a 50-50 split of men and women with the authors and the translators if it’s possible. It’s not always possible. There are some countries or cities where we go and we simply can’t find the women writers, sometimes because they’ve been so suppressed, or because they’re scared.”

NICKY HARMAN: “There are very many women authors in China. I don’t know whether there are more males than females. But I know who gets the prizes: it’s men who get the prizes.”

JEN CALLEJA: “There are issues in the whole infrastructure, and then in the publishing industry there still isn’t parity for women being published in English, let alone in translation. And then in reviewing culture, we know that women aren’t reviewed as much as men. So the problem is from the top to the bottom. There are obviously other issues, such as class, so for example if you translated a woman, because of the class structures in other countries you’re translating women who are predominantly upper or middle class: they get translated, but what about all the working-class authors?”

ANTONIA LLOYD-JONES: “I feel that if we understand another culture, if we read its books, watch its films and so on, then we find out that we’re all very much the same. And to me that’s important, it’s something we need in today’s world.”

JEN CALLEJA: “We push for translation into English because we need it. I mean that in an existential, soul sense; we’re starving for outside voices.”

NICCI PRAÇA: “I see translated literature growing, particularly if our borders shrink, but especially because younger generations, from the millennials down, are really keen to find out about what’s going on around the world.”

CAROLINA ORLOFF: “All of the Charco books so far stem from an impact in the societies of origin that I hope will translate into the English-speaking society. They bring philosophical questions, universal questions that are important for all of us, whatever the language or the society. And the translators have to understand, have to have a relationship with the story, the book, the universe that they’re going to translate, that is beyond the semantics of the language.”

BECCA PARKINSON AND ZOË TURNER: “People will automatically go for something that they think they will relate to. And if we’re not being shown that we can relate to these works from other cultures across the world, if they’re being ‘othered’ in our narratives, then without even thinking about it people won’t pick them up.”

CÉCILE MENON: “I’m publishing books that I think will have a connection with the previous books that I’ve published. And yes, which I think are relevant to a British readership.”

CHARLOTTE COOMBE: “Translated literature already faces one hurdle, its perceived ‘foreign-ness’ which some (not all) publishers and booksellers see as a barrier to sales. Then if you throw ‘women’s’ into the mix, the hurdle doubles in height.”

ANTONIA LLOYD-JONES: “One reason why the translator’s name should be visible is that we’re still having – in translation into English in particular – to change the imbalance in attitude to books that are published in English and books published in translation. People have a kind of allergy to things foreign. And look what’s happening to our world: there are all sorts of barriers going up, but I feel I’m a barrier remover, I want people to feel they can read anything from everywhere, and not have a mindset that says ‘Oh, that’s foreign, so it’s not for me’ or ‘That’s translated, so it can’t be any good.’ Unfortunately that attitude does exist, a lot of people think like that without even being aware of it. So the more you normalise translated literature by having the translator’s name mentioned alongside the author’s, the more it simply becomes an accepted part of all literature. And that should be the normal state of affairs.”

CAROLINA ORLOFF: “That duality – on one hand we’re keen to give prominence to our translators, they’re always on the cover of our books, as well as our copy editors, who are always on our back cover, but then on the other hand, we want to overcome this block from so many readers in relation to translated fiction, that they would immediately understand translated fiction as something that’s niche, difficult, too complex, and we just want to prove that that’s not the case. So it’s a balancing act, that we try to do with every book.”

NICKY HARMAN: “I think Chinese women writers all acknowledge the fact that they have less visibility … there’s certainly a dominance of men amongst writers and publishers.”

SOPHIE LEWIS: “I think publishers need to go a little bit further in the work that they do, or in the tentacles that they reach out, assuming that they do, in order to hunt down the women that they want to publish, to give them a better chance of making it over into another language.”

NICCI PRAÇA: “Small independent publishers who publish women in translation are activist publishers. They’re the ones who see that there is that there is a gap in the market which needs to be filled. I think that’s why I prefer independent publishing, because a lot of it is driven by gaps in markets and people’s passion to fill those gaps.”

CAROLINA ORLOFF: “Independent publishers working with translations have an opportunity to change that balance, to re-balance as it were, and make that balance right, to bring women’s voices to be at the same level as their male counterparts.”

NICKY SMALLEY: With translation specifically, there’s a real issue of women in other countries not necessarily getting the acclaim that brings them to our attention. This is definitely not an excuse, but if those women writers in other countries are not getting the acclaim for their writing that they deserve, then they’re not going to find agents who will take them into English. So that’s a key issue. And it’s a push and pull thing, because if English-language publishers are looking for more writing by women, then you create an awareness in other countries that this is something that’s desirable.”

CÉCILE MENON: “Generally, the books that I take on are by authors who haven’t been translated into English before, have been overlooked. They were considered as too niche or not commercially viable. A prime example of that was Translation as Transhumance by Mireille Gansel, translated by Ros Schwartz, which turned out to be one of our two best-selling titles and was selected for events at Jewish Book Week and the Edinburgh International Book Festival.”

ROS SCHWARTZ: “Independent publishers are essential, because they can make those decisions and there’s no finance department telling them they can’t do it. And booksellers are essential as well.”

SOPHIE HUGHES: “A truly wonderful thing about literature is that it’s never too late to redress the imbalance […] every writer has their time to be read. All of those silenced voices are still out there, waiting to be read. It is still perfectly within our power to do those writers the service of reading them.”

CAROLINA ORLOFF: “We’ve had a lot of support from small independent bookshops, but there needs to be a bigger movement from bigger companies, where they give more prominence to other regions or small publishers, because if you don’t see a book then you might not buy it. If Waterstones, for example, give prominence to a particular publisher, it can have a real impact. So we can only hope. We need to provide a more diverse array of fiction and worlds and voices for people to read – or not read, but our commitment is that they should be there.”

BECCA PARKINSON AND ZOË TURNER: “We need to get people over the idea that if it’s translated it’s going to be difficult. Maybe bookshops and libraries need to give us a bit of a hand in the marketing. You need a bookseller or a librarian or a reviewer to pick a book up and say ‘this is special’ and add their voice to yours. But especially as an indie, you’re going up against much bigger dogs in the industry, and then you’ve got Amazon, you’ve got a lot of people fighting against you. You’re not getting your books on the Waterstones front tables, you’re not on the Amazon homepage, so how do people find you? But the audience is there, and it’s growing.”

NICKY SMALLEY: “Publishers are obviously gatekeepers to an extent, but different publishers have different degrees of power in their gatekeeping, as do booksellers. So a chain like Waterstones has the power to make or break a writer.”

JEN CALLEJA: “People are still challenging the idea that there is gender bias in literature, and so firstly there has to be an acceptance that it exists. You have people who are consciously opting into publishing women, making those kind of changes, but it has to be a long-term thing. So it might be that for the next year or two people make a big thing of publishing women to push it forward. But people are so reactionary against that kind of positive discrimination without really acknowledging what comes before it. It doesn’t happen in a vacuum, it happens in a historical context. So it’s about making some real choices about women in translation, making an effort to work with women translators, using that as a consultancy basis to find more women.”

BECCA PARKINSON AND ZOË TURNER: “If more festivals invited over authors who aren’t from the UK and fought those visa battles, there wouldn’t be a news story about visas getting turned down. That shouldn’t be news, it shouldn’t be happening in the UK, but this insular atmosphere at the moment is focusing on British authors. It’s just so wrong and the opposite of what we should be doing.”

CHARLOTTE COOMBE: “The more we talk about books by women or translated by women, the more mainstream this thinking becomes. And more normalised, less ‘niche’. Women are not niche. But women’s writing is perceived as such.”

SOPHIE HUGHES: “Gender equality to me doesn’t mean always finding an equal number of women and men to read, review, publish, laud. It is about calling out injustices in order to slowly forge new taboos: for example, the taboo of talking over or speaking for women”

ROS SCHWARTZ: “What we can do about it is that as translators, we need to seek out those books and take them to publishers. It’s as simple as that. Publishers are busy people, they get bombarded the whole time from every foreign publisher on the planet sending them books for consideration. And the only way we can change things is by actually seeking out really brilliant books and taking them to publishers. And that does happen, and it is happening.”

Jen Calleja, translator from German

Charlotte Coombe, translator from Spanish

Nicky Harman, translator from Chinese

Sophie Hughes, translator from Spanish

Sophie Lewis, translator from French and Portuguese; co-founder of Shadow Heroes

Antonia Lloyd-Jones, translator from Polish

Cécile Menon, director of Les Fugitives

Carolina Orloff, co-director of Charco Press

Becca Parkinson, engagement manager at Comma Press and Zoë Turner, publicity and outreach officer at Comma Press

Nicci Praça, formerly publicist for Fitzcarraldo Editions; manager of Amnesty Kentish Town bookstore

Ros Schwartz, translator from French

Nicky Smalley, publicist for And Other Stories