Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Mark

4 November 2019Nicky Harman is a translator from Chinese. She is co-Chair of the Translators Association (Society of Authors), and closely involved with Paper Republic, an online publication initiative promoting Chinese writing in English translation. She taught on the MSc in Translation at Imperial College until 2011 and now translates full-time. On 31 October Nicky gave a fascinating talk at the Translating Women conference, in which she discussed an interview series she had carried out with Chinese women writers, focusing on the barriers they face within a literary system that disadvantages women and makes assumptions about what they must write about – you can see comments on this and other conference sessions on Twitter, under the hashtag #TWConf19.

How do you find new works in Chinese, and do you work more with pitches or commissions?

I wish I could say that I looked at all new work coming out very systematically, but I really only touch the tip of the iceberg. China is such a big country that I’ll probably get to the end of my professional life never having read things that I still want to read. As a professional translator, I like it when publishers come to me, when they’ve already chosen a book and have bought the rights. That’s been the case with the majority of the work I translate. The other way is networking: word of mouth, people recommending books… recently when I was in China I was asking women which women writers they liked. Having said that, pitching to publishers is quite difficult and time consuming. With Chinese there are a couple of different problems. One is that a lot of publishers don’t know much about Chinese writers so they don’t know what they’re looking at or for, and when they find it, they may not like it.

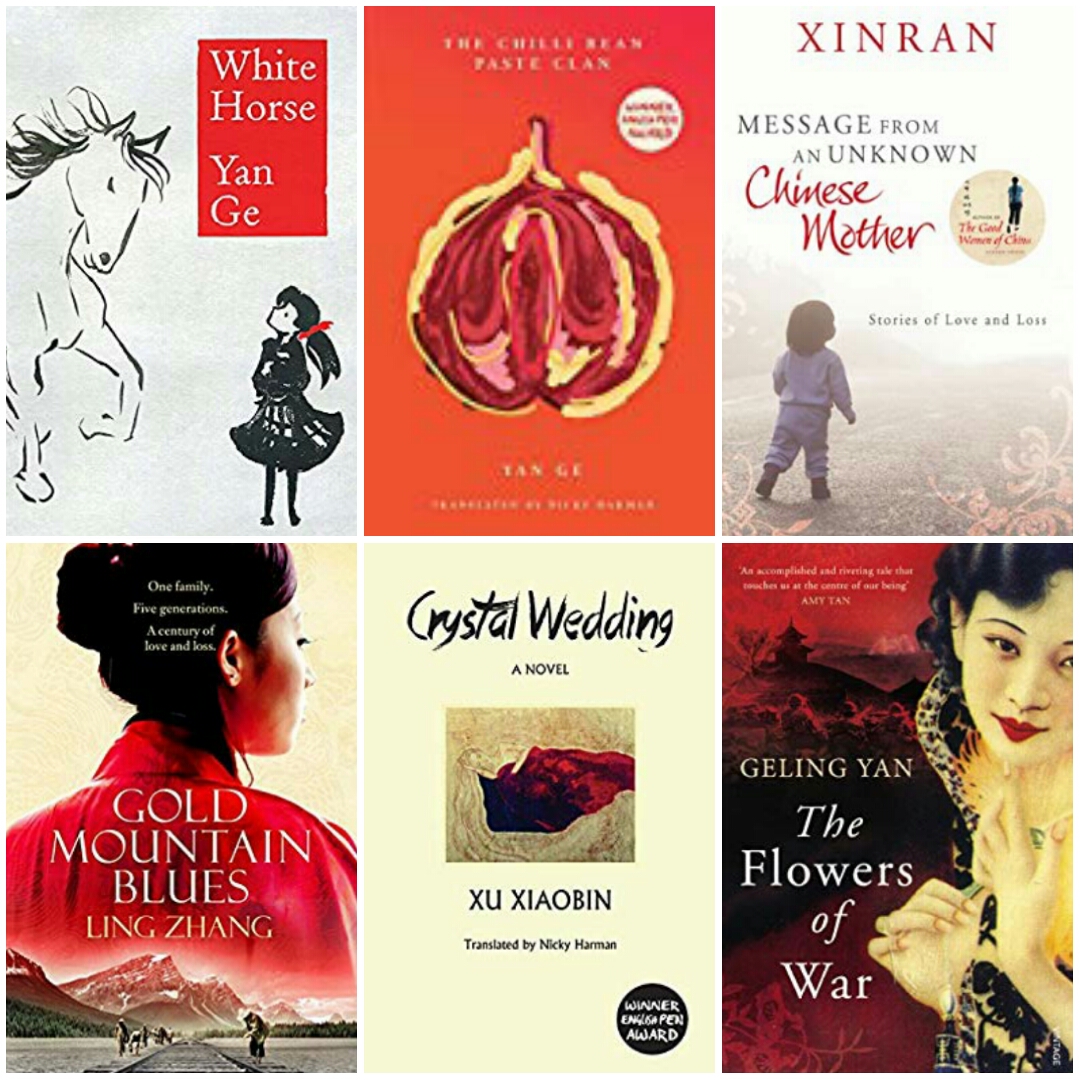

What in particular drew you to The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, by Yan Ge?

I loved the voice from the start. It was so natural and funny and rude and disrespectful, but also utterly unassuming and unpretentious. Yan Ge allowed the voice of this really bad man to just come through completely naturally. And I loved it: it was so accessible, so readable. I didn’t realise quite how interesting the language was until I started translating it; the dialect caused me some problems. Yan Ge and I started communicating after I finished the translation, but before the publisher had been found, and she pointed out that in a lot of areas in my translation of the dialect I either hadn’t got really into the meaning of that particular fruity expression or I’d misunderstood it. In one case, she said there were too many “fucks”, so I went through, and I counted that there were exactly the same number of fucks in the English plus two which were verbs because the verb “to fuck” in Chinese is different from the noun! But I took her point, and so we went through and started adding more colourful expressions. I really had to be creative, because English doesn’t have the same number of colourful expressions and obscenities.

Are there particular writers or genres in Chinese that are favoured by the regime?

That’s a really interesting question. The genre that has really worked from Chinese is sci fi. Second to that the Wu Xia, the martial arts fiction. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that they’re favoured though, because the atmosphere is so constrained and constricted in China. And that goes for the intellectual world, the literary world, the artistic world: the clamps have really come down. Xi Jinping has made China a very repressive place, and there’s also a fair amount of discussion about whether science fiction can be a route for writers to express their dissatisfaction with the regime. Martial arts fiction is unlikely to get on the wrong side of the regime. But there have been various sci fi works which have gone a little bit close to the edge; in particular, Hao Jingfang’s novella Folding Beijing is all about how Beijing turns into a collapsible three tier city, where by night and by day different layers come out. And by night it’s the migrant workers, cleaners, garbage collectors and so on who come out, and are not allowed to mix with the more well-to-do people who only come out during the day. So the very fact that she’s pointing out the class difference and the underworld in Beijing could be considered a bit risky.

There are beginnings of a move away from eurocentrism in translated literature – how have you perceived this over time, and how do you think we can foster this?

Looking at a list of the last 6-7 years, the main publishers who published from Chinese were either university presses, or one-man or one-woman bands. This is not necessarily a good thing; the tiny publishers can be great but also a bit precarious. I hope that mainstream independent publishers will take up books from Chinese. Some do, and then half your promotion is done because the readers will have heard of the publisher and so they’re more likely to go for the book. It’s all part of this strong feeling I have that literature translated from Chinese has got to become mainstream. It’s got to be something that readers pick up and read for enjoyment, otherwise we’ll be stuck with good books that have no readers, which is a tragedy. What’s the point of translating them if people don’t get to read them? I’m still learning, and I’ve reinvented myself as a part-time promoter of the books I’ve translated, but also with the work I do on Paper Republic, which is now registered as a charity in this country promoting Chinese literature in translation generally; there are about five of us all working together and we’re all translators in different parts of the world. But regular book reviews, it seems to me, are like hen’s teeth.

You’ve mentioned that there is a marked gender bias in Chinese literature; how does this affect who gets published and who gets translated?

There are many women authors in China. I don’t know whether there are more men than women, but I know who gets the prizes: it’s men who get the prizes. I looked at the Mao Dun Prize (a prize for novels in Chinese sponsored by the China Writers Association) over the last ten years, and found that a very small minority of the winners were female writers. And when we do our end-of-year statistics on Chinese writers translated into English, a great majority will be male writers translated into English and a small minority female writers. I think it’s much the same all over the world. I’m very wary about making generalizations about China because it’s such a big place, but I think women writers all acknowledge the fact that they have less visibility. There’s certainly a dominance of men amongst writers and publishers in China. And the publishers are the ones who will package someone’s book and try to sell the rights to western publishers for translation.

You work with a number of networks; can you tell us more about Paper Republic in particular, and the activities you undertake beyond (and behind) translation?

I’ve been involved with Paper Republic for the past ten years. It started off as a blog where translators could post their questions and write funny posts, and it has expanded to have a big database to link to other articles and to provide a resource not just for translators but also for readers and for anyone wanting to dip a toe into Chinese fiction and translation. We regard ourselves now as almost all outward facing; we’re looking outwards to the readers, doing promotional work of various kinds, educational work, and we’ve got big plans. It would be lovely if we could get money. But in the meantime, we’ve actually done an awful lot without any money at all, both by working as volunteers and by drawing on the goodwill of the translation community. A surprising number of translators from Chinese have a short story squirreled away that they’ve never had published or that they’d like to see published again, and so we’ve done a whole series of nearly 70 short stories which we’ve put out under the rubric “Read Paper Republic” over the last three years; that’s an ongoing project.

Do you think that China is under-represented in translated literature? And as far as you know is this common across European literatures, or is it an Anglo-American issue?

It’s a complicated question. There is a certain resistance in the English-language publishing industry. But is there something particular for Chinese which makes it hard to sell the rights of a Chinese novel into English? Chinese writing is very different, and one of the things I like about Yan Ge is that she isn’t that different, whereas a lot of Chinese writers do write very differently, which is to do with the history of literature. It’s partly that genres are different: novels can be very long, and in the last century there were a lot of very didactic novels (and that actually predates the Communist Party and the 1949 revolution). Then after that, Chairman Mao insisted that writers had to present a good picture to the world. When you translate a lot of Chinese novels you constantly come across things which refer to cultural or political phenomena. For example, if there’s a casual reference to the Cultural Revolution, you have to think about whether you’re going to gloss it, or just mention it and hope that the reader will understand. There are cultural things lurking under the surface. So there’s a whole cultural and political burden of information and the translator can deal with it, but it just makes more for the casual reader to take on board.