Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Mark

27 January 2022For my first review of 2022, I had the pleasure of reading the first two releases from new publishing house Praspar Press. Founded in 2020 by Jen Calleja and Kat Storace, Praspar Press aims to bring exciting contemporary literature from Malta – written in English or translated from Maltese – to Anglophone readers. You can read my interview with Jen and Kat for more insight into their mission and passion, and check out their website to get to know Praspar.

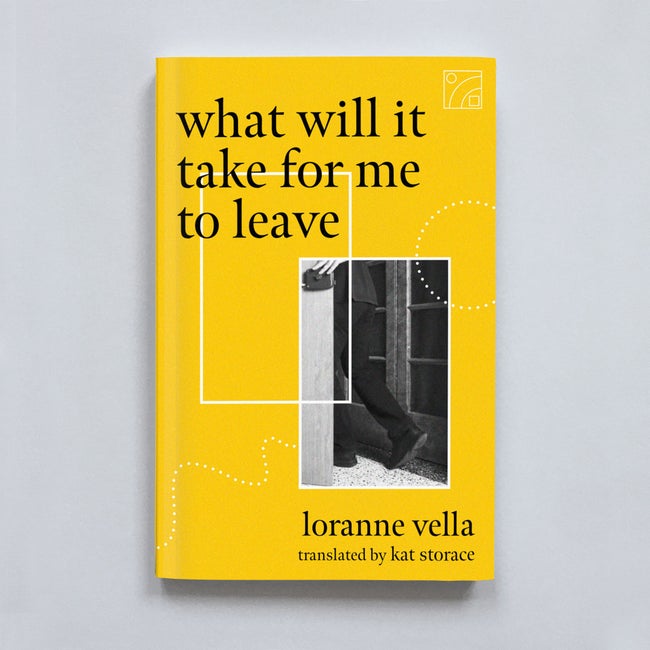

I’m focusing mostly on Loranne Vella’s collection of short stories What will it take for me to leave, translated by Praspar co-founder Kat Storace, but I must also give a mention to the anthology of short stories Scintillas: New Maltese Writing 1. I mentioned in my interview feature with Jen and Kat that I have next to no knowledge of Maltese literature (very embarrassing since I’m from a Maltese family), and I suspect that most Anglophone readers will find themselves in a similar position, as the press was set up in part to respond to the lack of writing from Malta available in English. So the anthology of short stories Scintillas offers an excellent introduction to the dynamic and diverse writing currently being published in Malta: as individual pieces they are innovative and contemporary, as a collection they felt to me at once nostalgic, rooted in their land, and outward-looking, whether towards other shores or alternative futures. Of the sixteen contributions (a combination of short stories and poems) that make up the collection only four were translated; I don’t know whether this is representative of writing from Malta more generally, but I did notice how many of those written in English interspersed the narrative with words and phrases from Maltese (some of which led me down a childhood-memory-rabbit-hole worthy of Proust’s madeleine). Particular standouts to me were the outrageously edgy “Basically Amazing” by Sebastian Tanti Burlò, the perfectly observed interactions in Alex Vella Gera’s “The Time is Right About Now” and the restless melancholy of Daniel Vella’s “The Lights That Call Her On”. Scintillas also features an excellent short story by Loranne Vella (“night”), translated by Storace and offering a taster of what you can expect in the full collection that I’m going to focus on here.

The stories in What will it take for me to leave are very short indeed – sixteen of them in just over a hundred pages. Yet they offer detail enough to give the impression that the characters are well known, conveying multitudes in few words. Storace translates this expressive concision superbly, drawing on a broad lexical range and ensuring each story has its own identity, even if there are common or recognisable features that bring them together. The Maltese title of each story is printed below the English title, a detail I greatly appreciated – whether the English words were identifiable in the Maltese ones or not, I liked the visibility of this as a translation, the locating of the stories as having first existed in another language.

The stories in What will it take for me to leave are rooted in the everyday – doing a jigsaw, baking a pie, renewing contact with the object of a teenage crush, a sleepless night, a bitter quarrel ten years into a relationship – yet they are united by a richness of emotions, reflections and unpredictability. The first story in which the ending took me by surprise was “cup of coffee” (“kikkra kafè”), which at first seemed to be leading in a clear direction and I was only hoping the resolution wouldn’t be too saccharine. Not only was there no saccharine in sight (here or anywhere else) but the ending veered off in an entirely different direction, in an excellent example of how Vella eschews predictable outcomes for her characters (in almost every story I was caught by surprise by the final twist). There is a touch of the surreal, as in the brilliant vignette “on hold” (“telefonati”), and throughout the collection things are rarely as they might at first seem.

The title of the collection comes from the first line in the story “disappearing act” (“baħħ”), a sub-2-page reflection on the merits of leaving. Leaving what/where/whom is something I’ll leave you to read for yourself (to be honest, I’m not sure I could do justice to it if I tried to explain it anyway), and showcases once more Vella’s flair for the unpredictable.

I was particularly interested in the way women are represented through the collection: there are subtle observations on the expectation of artifice in “layer by layer” (saff saff”) and the drudgery of traditional gender roles in “ricotta pie” (“torta tal-irkotta”), but some more edgy takes on contemporary womanhood in “window shopping” (“fil-vetrina”) and an unexpected twist in “good Samaritan” (“is-samaritan-it-tajjeb”) that felt like a sharp yet good-natured reminder not to judge where Vella might be taking her characters.

This is Storace’s first book-length translation, and it’s a great debut. The attention to the sensory evocations of language is excellent, the naturalness of everyday expressions is admirable, and there are words I paused and read over and over, they were so perfect (whether in the higher register of a “bilious” exchange between two sisters-in-law or the lower one of “a fuck-off tin of holy wafers”). The sentences are often quite long, with multiple clauses, and Storace ensures that they never appear convoluted or awkward. I also loved the occasional word being left in Maltese – I dislike responses to translations that find this practice alienating or lazy – firstly [forgive me for mounting my translation soapbox], I don’t think we should expect literature to come to us looking comfortably familiar, and secondly, I felt that Storace’s judicious choices of when to do this helped transport me to a different place, one where I might conceivably attend a Politeknik or have a kafettiera “bubbling away on the hob”. Storace makes judicious choices here: the words left in their original form are always recognisable (though I confess to initially wondering what a “polite knik” could be, before feeling very foolish indeed).

There is a love of Malta evident in several of the stories, but this is never rose-tinted or overly sentimental: it is far more about “loss and losing” than it is about wilfully naïve nostalgia. Overall this is an accomplished and memorable collection, an excellent translation, and a great start to the catalogue for Praspar Press.