Haemochromatosis: genetic iron overload disease

Summary for patients

Haemochromatosis: genetic iron overload disease

Summary for patients

Haemochromatosis is a genetic disease characterised by having too much iron in the body. An accumulation of iron across the body can be harmful to vital organs including the liver, pancreas, and joints. Due to an overload of iron within such areas of the body, diseases such as fibrosis and cirrhosis, liver cancer, diabetes and osteoarthritis can develop [1-3].

What causes haemochromatosis?

Haemochromatosis is primarily caused by a faulty HFE gene (having two copies of a mutation known as HFE C282Y), close relatives of those carrying two copies of the C282Y gene could also be at risk of haemochromatosis. See below “HFE genotypes” section for further details. Risk in each individual can be further modified by other factors (see Risk Modifiers page).

Signs and symptoms of haemochromatosis

Sufferers of this iron-overload disease can build up iron in their organs throughout life. This can present itself through the following signs and symptoms, which typically are worse in men and occur later in life [1-3]:

Of course, there are lots of other causes of all of these symptoms and signs, even in people with the higher risk C282Y double variant. For example, obesity is a big risk factor for diabetes with or without the gene variants, and iron can deposit in the liver in fatty liver disease, even in those who have no haemochromatosis gene variants.

How is haemochromatosis diagnosed and treated?

Haemochromatosis can be diagnosed with a simple blood test to check iron levels, which if high can be confirmed with a genetic test (to test for faulty copies of the HFE C282Y and H63D gene – see below section). Haemochromatosis can be safely treated by the removal of blood (known as venesection or phlebotomy) to lower iron levels. Although phlebotomy works well for preventing liver disease, its effect on diabetes and arthritis is uncertain and needs more study.

HFE genotypes: how do we know what they do?

The HFE C282Y and H63D genotypes are two variants of the HFE gene; this gene plays a vital role in iron metabolism in the body. Being a carrier of either C282Y or H63D can increase the susceptibility of being diagnosed with iron overload-related haemochromatosis disease.

There have been many studies of groups of people with the different genetic variants, including blood iron measures and liver iron measures. In the UK, we have the worlds largest study, with details of NHS diagnoses, cancers and deaths. We have used this study, called UK Biobank, to check diagnoses in nearly half a million people over 20 years. This helps us compare people with and without each genetic variant; this is important because there are other causes of higher iron measures and the features like fatigue, liver disease, arthritis and diabetes are common in people without haemochromatosis too.

HFE genotypes: how common are they?

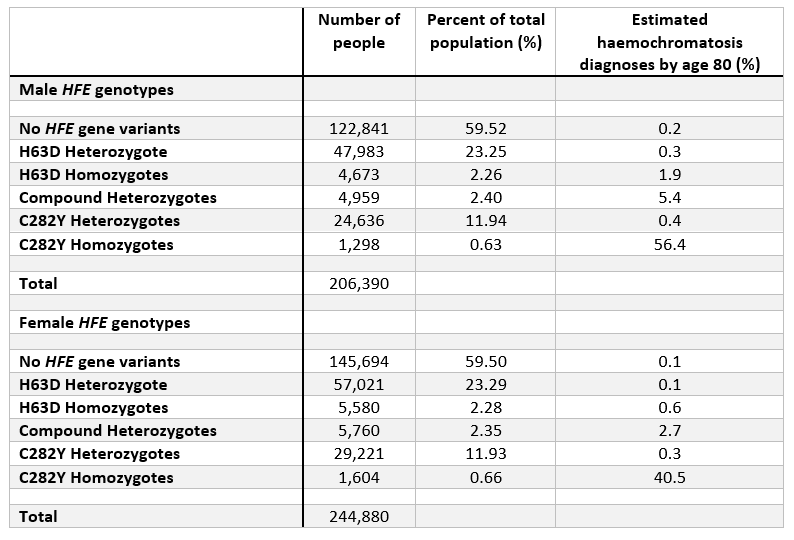

The table below highlights the overall frequencies of each genotype in the UK Biobank participants of European genetic ancestry (see below section for note on ancestry), categorised by males and females. Additionally, the table shows the estimated percent diagnosed with haemochromatosis by age 80 years in each genotype.

Note: “homozygote” = 2 copies of genotype. “Heterozygote” = 1 copy.

Genetic ancestry

The HFE C282Y genetic variant is most common in populations that migrated from Northern European countries, especially those of Celtic origin. See the Other Risk Factors page “Genetic Background” section for details on C282Y prevalence across European populations.

How common is haemochromatosis?

During the baseline assessments conducted by the UK Biobank between 2006 and 2010, it was observed that the prevalence of haemochromatosis varied among different genetic groups [1]. In male C282Y homozygotes, the prevalence was 12.1%, while in female C282Y homozygotes, it was 3.4%. The prevalence decreased in descending order among compound heterozygotes (0.6% and 0.2% for males and females, respectively), H63D homozygotes (0.2% and 0.03%), C282Y heterozygotes (0.1% and 0.017%), H63D heterozygotes (0.03% and 0.01%), and finally among individuals without faulty HFE gene variants (0.02% and 0.005%), again for males and females, respectively.

Further information and support

For further information on haemochromatosis please visit:

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/haemochromatosis/

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/hemochromatosis